The Vancouver-based real estate magnate and collector Bob Rennie has given a collection of contemporary art worth more than C$12m to the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, in honour of Canada’s 150th anniversary. The donation by is “by volume and value, the largest single gift of contemporary art in the history of the gallery,” the museum’s director Marc Mayer says.

The Rennie Collection is known for its focus on works tackling issues of identity, social commentary and injustice. Most of the 197 paintings, sculptures, and mixed-media pieces in the collection are by Vancouver artists like Ian Wallace, Rodney Graham, Damien Moppet, Brian Jungen and Geoffrey Farmer—who is representing Canada at this year’s Venice Biennale—but it also includes a work by the Colombian artist Doris Salcedo, Tenebrae, Noviembre 7, 1985 (1999-2000), inspired by the torching of the Palace of Justice in Bogotá, which killed 100 people.

Stand-out pieces include Farmer’s A Pale Fire Freedom Machine (2005), an installation in which furniture is burned and its ashes transformed into ink that is used to pen a manifesto, and Wallace’s Poverty 1982 series, which features fictionalised images of homelessness silk-screened onto eight colourful panels.

“Bob is one of the most sophisticated collectors in the contemporary art world,” Mayer says. “We are grateful that he is thinking of us and the whole country through this remarkable gift that will allow us to be custodians of these wonderful works and make them available for Canadians, to study, share and enjoy.” In recognition of Rennie’s gift, a gallery at the museum will be named after him.

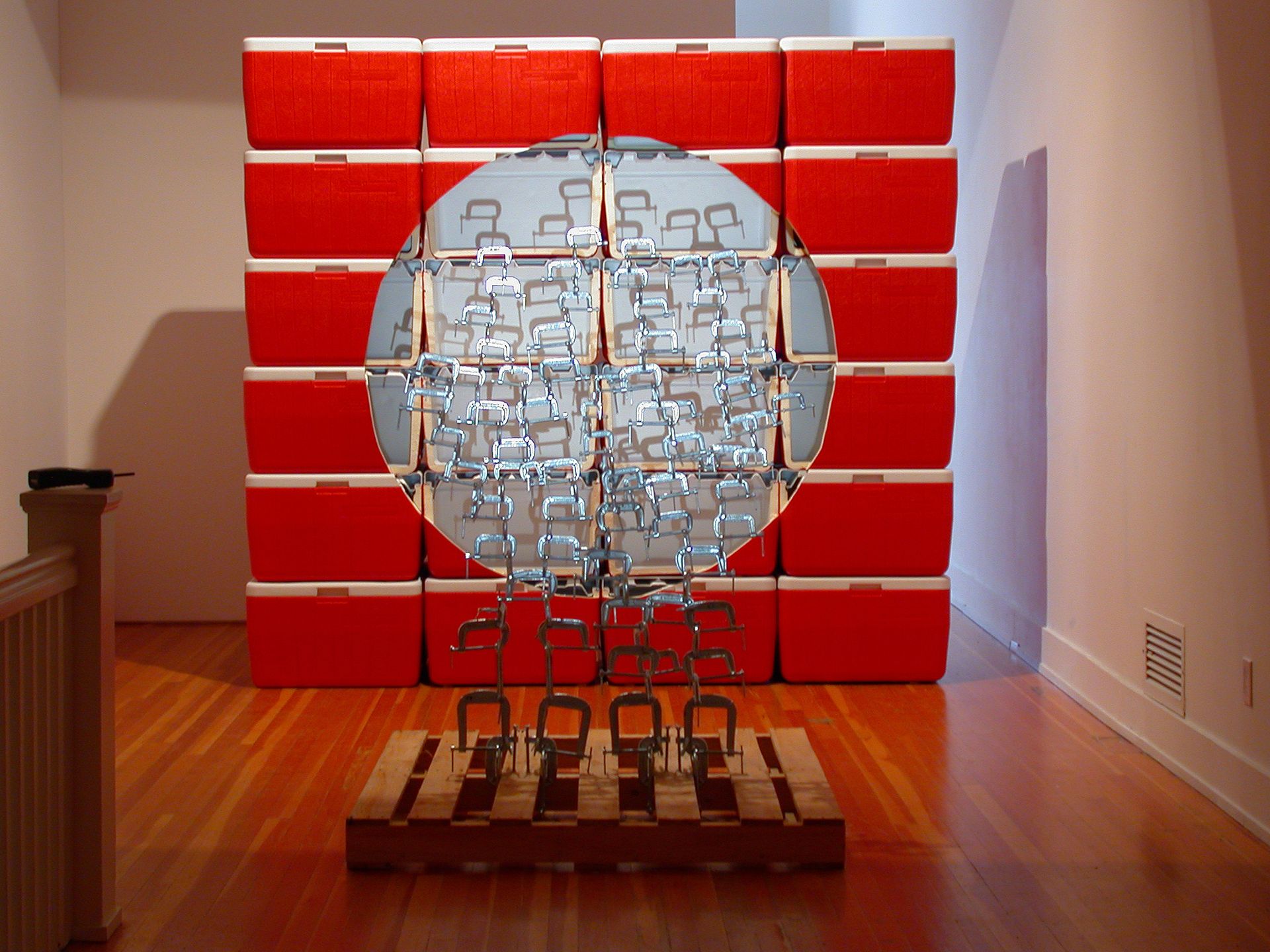

Rennie says the idea for the donation was a “conversation that evolved over several months” and was an extension of his long-running relationship with the institution. In 2012, he donated Brian Jungen’s work Court, an installation of sewing tables that form a basketball court, evoking the sweatshop labour behind the production of professional basketball shoes and equipment.

It was also inspired, Rennie says, by a desire to keep his holdings of an individual artist’s work together so they could be studied in depth and borrowed when needed. The works by Wallace, for example, join a series of photo-lamination canvases, Abstract Paintings I-XII (The Financial District) (2010), donated by the artist in 2014, as well as the archive Wallace plans to give the National Gallery in a decade.

Rennies’s donation will allow the National Gallery to organise retrospectives of artists like Wallace, Moppet and Jungen, Mayer says. A large selection of Moppet’s works on paper from the gift, for example, will be shown along with his father Ron Moppet’s art in May, and in the Canadian Biennial in October. It also means “we can lend these works to other galleries who want to do exhibitions”, Mayer says, noting that the National Gallery of Canada is the largest institutional lender in Canada, sending out more than 800 works a year.