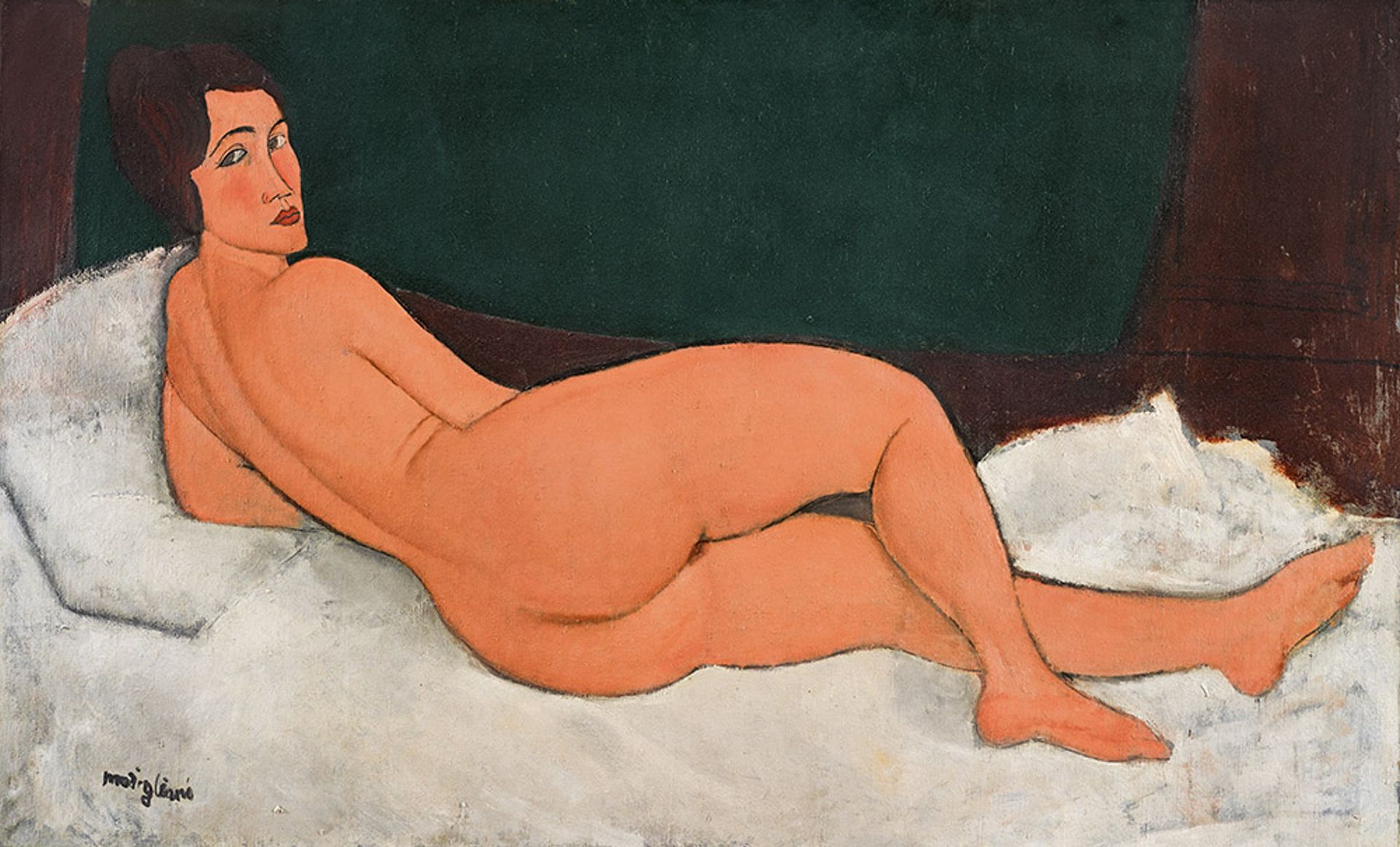

Kicking off New York’s third straight market week, after the Frieze and Tefaf fairs and Christie’s Rockefeller extravaganza, Sotheby’s evening sale of Impressionist and Modern art on 14 May rang up $318.3m. Although that number appears to nearly double last year’s take of $173.8m, and even improve on November’s $269.7m result, nearly half was thanks to a single work: Amedeo Modigliani’s Nu couché (sur le côté gauche) (1917), which contributed $157.2m with fees.

With the auction record for a Modigliani nude standing at $170.4m, there was reason to believe that this example—some deemed it more commercially viable, given the subject’s more-demure pose; others said less desirable for being less explicit—could incite a bidding war. When lot 18, tagged with an estimate “in excess of $150m”, rolled around, two agonising minutes passed during which Patti Wong, chairman of Sotheby’s Asia, looked to be on the verge of jumping in. But there was ultimately no advance on the $139m offered by a buyer the auction house had lined up ahead of the sale with an irrevocable bid. The painting was immediately crowned the most expensive in the firm’s 274-year history by Helena Newman, the auctioneer and president of Sotheby's Europe and worldwide co-head of the Impressionist and Modern department.

Amedeo Modigliani, Nu couché (sur le côté gauche) (1917), sold for $157.2m Courtesy of Sotheby's

That paradoxically large yet unfulfilling result drained what energy had been built with a solid early battle for the sale’s other star, Le Repos, Picasso’s beatific 1932 portrait of his teenage lover, Marie-Thérèse Walter, which sold for $36.9m with fees (est $25m to $35m) to an Asian private collector on the phone.

After the sale, Simon Shaw, Sotheby’s worldwide co-head of Impressionist and Modern art, underscored the “velocity” of appreciation in the market for the top two lots, noting that the Modigliani last sold for $42m five years ago, and the Picasso for $7.9m in 2007. "It was a fantastic price for a fantastic picture", says Brooke Lampley, Shaw's colleague who heads the department in New York, of Le Repos. "But that person still got a bargain."

Pablo Picasso, Le Repos (1932), sold for $36.9m to an Asian private collector Courtesy of Sotheby's

The overall total might have been higher still if Alberto Giacometti's attenuated bronze sculpture Le Chat (1951/1955), estimated to fetch between $20m and $30m, had not been held back for the auction house's 19 June sale in London. Stripping away the Modigliani outlier, the auction looks far more modest, delivering $161.1m on 32 lots, 15 of which were guaranteed a minimum price by the auction house or a third party and sold on just one or two bids. Two pricey works without financial backing, Matinée sur la Seine (1896) by Monet and Sommernatt (1902) by Edvard Munch, struggled to crack their punchy estimates, making $20.6m and $11.3m against expectations of $18m to $25m and $10m to $15m, respectively.

More ominous, perhaps, were the 13 lots that went unsold as attention flagged in the room—including about half of the Picassos, which made up a quarter of the catalogue. Femme au chien (1953) was bought in at $11m, as was Femme assise (1949), at $5m. A tender Rose Period gouache, Famille d’Arlequin (1905), however, brought $11.5m from a bidder on the phone with Wong. Approximately 25% of the evening's buyers were Asia based, according to Sotheby's.

Picasso's Famille d'Arlequin (1905), a rare Rose Period gouache, made $11.5m Courtesy of Sotheby's

“The market is very discriminating”, says New York dealer David Nash. “If it’s high quality, it sells well, but if it’s mediocre, forget it.” Even after Picasso’s strong performance in London’s spring sales, Nash says he was not surprised to see so many falter here: “I thought they were really unattractive paintings, with the exception of Arlequin, which was beautiful but expensive”. Referring to the London spree by Gurr Johns’ Harry Smith, buying on behalf of an unidentified client, Tom Mayou, director of the advisory firm Beaumont Nathan, adds, “You have to wonder, when you have this kind of supply, what happens when you remove one big actor.” (The Picasso market will again be tested at Christie's on Tuesday night, where two major canvases have been pulled from the auction house's evening sale following damage sustained to one during the preview.)

Georgia O'Keeffe, Lake George with White Birch (1921), sold for $11.3m, double the $4m to $6m estimate Courtesy of Sotheby's

Where Sotheby’s succeeded without qualifier was with artists who even a couple of years ago might have been considered adjacent to the classically European Impressionist and Modern category: contemporaneous works by Americans like Georgia O’Keeffe and Mary Cassatt, and by Latin Americans like Rufino Tamayo and Joaquín Torres-García. O’Keeffe’s Lake George with White Birch (1921) incited a bidding war that came to rest at $11.3m with fees (est $4m-$6m), while Cassatt’s maternal pastel A Goodnight Hug (1880) fetched $4.5m with fees, a record for a work on paper by the artist.