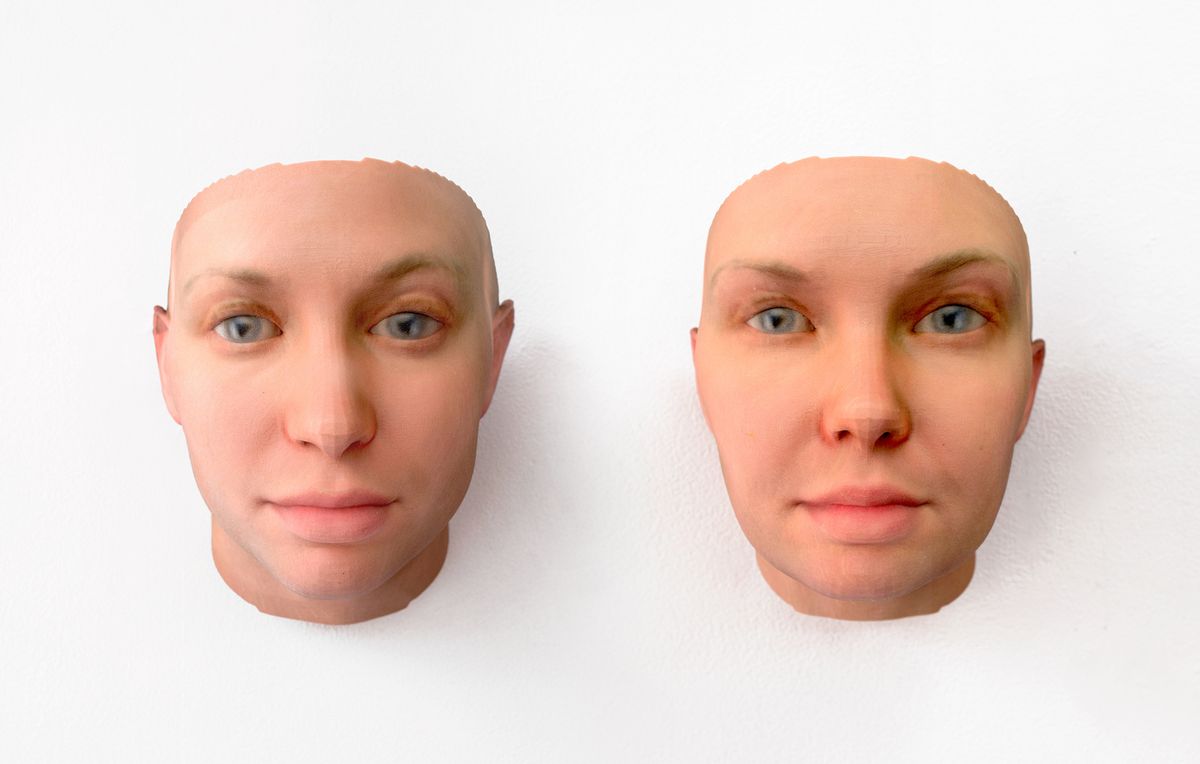

Who wants to live forever? We are all connected, but do we feel lonely? Should the planet be a design project? These are just some of the questions asked and tackled in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s The Future Starts Here (12 May-4 November) exhibition, which opens tomorrow. This show is the first to be organised by the museum’s Design, Architecture and Digital department and uses more than 100 objects, many on public display for the first time, to bring “live experiments about our future society from the studio and lab into the museum”, says the V&A's director Tristram Hunt. The pieces on show will range from products developed by major corporations like Google, Apple and Facebook and works by artists such as Tomás Saraceno and Miranda July to personalised tools made by a 70-year-old quadruple amputee to help with everyday tasks. Further highlights include portraits of Chelsea Manning generated from her DNA and the world's first zero-gravity 3D-printer.

If you missed the Charles I blockbuster at the Royal Academy of Arts last month, then you can have second bite at the royal cherry with the collection of his son, Charles II. But get up off your throne quickly, as Charles II: Art and Power (until 13 May) at the Queen's Gallery closes this weekend. Following the execution of Charles I in 1649, and the dispersion of his collection, his son Charles II remained in exile for 14 years until he returned to take the throne in 1660. He did not waste any time amassing his own formidable collection, which included works by Bruegel, Leonardo and Titian, among many others. One of the highlights of the exhibition is the majestic portrait (around 1676) of the Merrie Monarch himself by John Michael Wright. The painting is almost three metres high and depicts the king in parliamentary robes and newly wrought regalia—in an opulent display of power.

Also closing this weekend is Mark Dion’s solo show, Theatre of the Natural World (until 13 May) at the Whitechapel Gallery, of works made between the 1990s and the present day. Dion’s elaborate sculptures and installations use the methods and conventions of the natural-history museum display, the scientific field trip and the archaeological dig. But they do so to question the authority of our institutions and to examine our complicated—and conflicted—relationship with the natural world. For more than 30 years, the New York-based artist has travelled the world, collaborating with scientists, artists, museums and members of the public on works that shake up value systems and cast a critical eye on what we choose to cherish, conserve, exploit and discard. He has dredged a Venetian canal, excavated artefacts from the banks of the river Thames and established a marine-life laboratory using specimens from Chinatown in New York.