Mark Dion’s elaborate sculptures and installations use the methods and conventions of the natural-history museum display, the scientific field trip and the archaeological dig. But they do so to question the authority of our institutions and to examine our complicated—and conflicted—relationship with the natural world. For more than 30 years, the New York-based artist has travelled the world, collaborating with scientists, artists, museums and members of the public on works that shake up value systems and cast a critical eye on what we choose to cherish, conserve, exploit and discard. He has dredged a Venetian canal, excavated ancient and modern artefacts from the banks of the river Thames in London, established a marine-life laboratory using specimens from Chinatown in New York and, on a number of occasions, dramatically rearranged the collections of major museums according to his alternative and often highly subjective systems of classification. Dion’s solo exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, featuring works made between the 1990s and the present day, is due to open on 14 February. It begins with a major commission created especially for the show.

The Art Newspaper: What are you making for London?

Mark Dion: Unlike a number of artists who work with nature, I never make work directly about nature. I’m more interested in ideas about nature, and trying to understand how we got on this crazy path that seems to be taking us over a cliff-edge in our relationship to the natural world. If we want to understand how we’ve evolved this suicidal relationship, we have to follow our tracks back through history and understand where things started to derail. Like a lot of my works, it will deal with the compartmentalising of ideas and other taxonomies and categories of thinking about nature, but viewers will also be confronted with the chaotic aspects of nature itself. Although we think a lot about nature, nature doesn't really think about us very much, so in this first space [in the gallery], part of what happens is that we come to terms with the indifference of the natural world.

The Whitechapel exhibition is called Theatre of the Natural World, and many of the works here take the form of elaborate theatrical mises en scène.

When I was at school, theatricality was a term used by the oppressive, ever-present, Minimalist hegemony to deride things. There was nothing you could be that was worse than theatrical. So for me, that indicated something of real interest. If the mantra of the Minimalists was, “it is what it is”, then I was, like, “not so fast—it might be what it isn’t”. This became a really instructive way for me to look at things, and to take that attack through the back door of these pedagogic museums and to look at things that a certain kind of rigorous scholarship really dislikes but that the public is very engaged with. I think the public have this intuition that it is more powerful and meaningful to see things in their actual context rather than ripped away and in isolation.

What drew you to the world of natural history and science as a mode of investigation?

I think most artists are motivated by what they love the most, and my engagement with the natural world came from a personal commitment. I always had a relationship with the outdoors that was very hands-on. I hike and I fish and I’m a pretty serious birder. Where I grew up in Massachusetts, I could be at the beach on my bicycle in 15 minutes, but I could also be in the heart of a really gritty post-industrial city. If I went in the other direction, I would pass farmlands and be in a forest. When I was a student, I was studying with these very theoretical people, so I had this intense theoretical world with my friends, and then on the weekends, I had this other world of a bird-watching and fishing and hiking group of friends. It took a long time to bring those two worlds together.

What tipped the balance?

In the early 1980s, the art world was delving into a kind of warm-over of Pop art through appropriation and a rediscovery of the pleasure of Expressionism: questions I thought were very narrow, constraining and unengaging. But when you walked into the natural-history museum and the science museum, the questions were enormous—they were really existential and philosophical and dynamic and important. So I just found myself gravitating more and more towards the kinds of institutions that were asking really essential questions.

You seem to celebrate and critique the methods, systems and conventions of how we deal with nature and natural specimens.

I’m not really interested in the neutrality that the museum struggles for. To me, neutrality is sterile. It’s like distilled water—there’s no taste; there’s nothing there. I want to direct viewers. I want to give them clues as to what I’m thinking about, because the work also plays with a sophisticated reading and contradictions—one piece might say something and the other piece might seem to argue the opposite. I want to give viewers a lot of power and control over discovering their own position in relationship to the works, which are suppositions, not declarative statements.

The wunderkammer or cabinet of curiosities is a model that you repeatedly revisit. Why?

The interesting thing about the wunderkammer is that there is no one wunderkammer—they’re all different. Each one is a distinct reflection of the individual who created it and their access to materials. The imperial museum is representative of the triumph of science: whether they are in Tokyo or Kinshasa or Rio or London or Houston, there’s this notion that the museum should have a similar model to talk about evolution, taxonomy and systematics, whereas the wunderkammern are the reflections of these quirky individuals. They are pre-scientific; they still have one foot in the world of magic, and what that means is quite different from one organiser to another. They’re so idiosyncratic and so strange, and you can get yourself into trouble organising your wunderkammer—I find all that very interesting.

The natural world is in unprecedented danger—how has this affected your work?

We are now in such a dramatically hostile relationship to the environment that I feel there has to be a return to a more directly environmentally oriented project, which I have been trying to do. But at the same time, I am extremely dismayed by the lack of organised alternatives. To promote progressive culture, you need input from all sorts of different types; so you need activists, but you also need artists who help to foster this affection for the natural world by painting pretty pictures. I’m like an artist version of a historian of science. I’m trying to understand the underpinnings of how we got here, but my tools are materials. I’m a sculptor and an installation artist, but I share some of the same goals.

• Mark Dion: Theatre of the Natural World, Whitechapel Gallery, London, 14 February-13 May

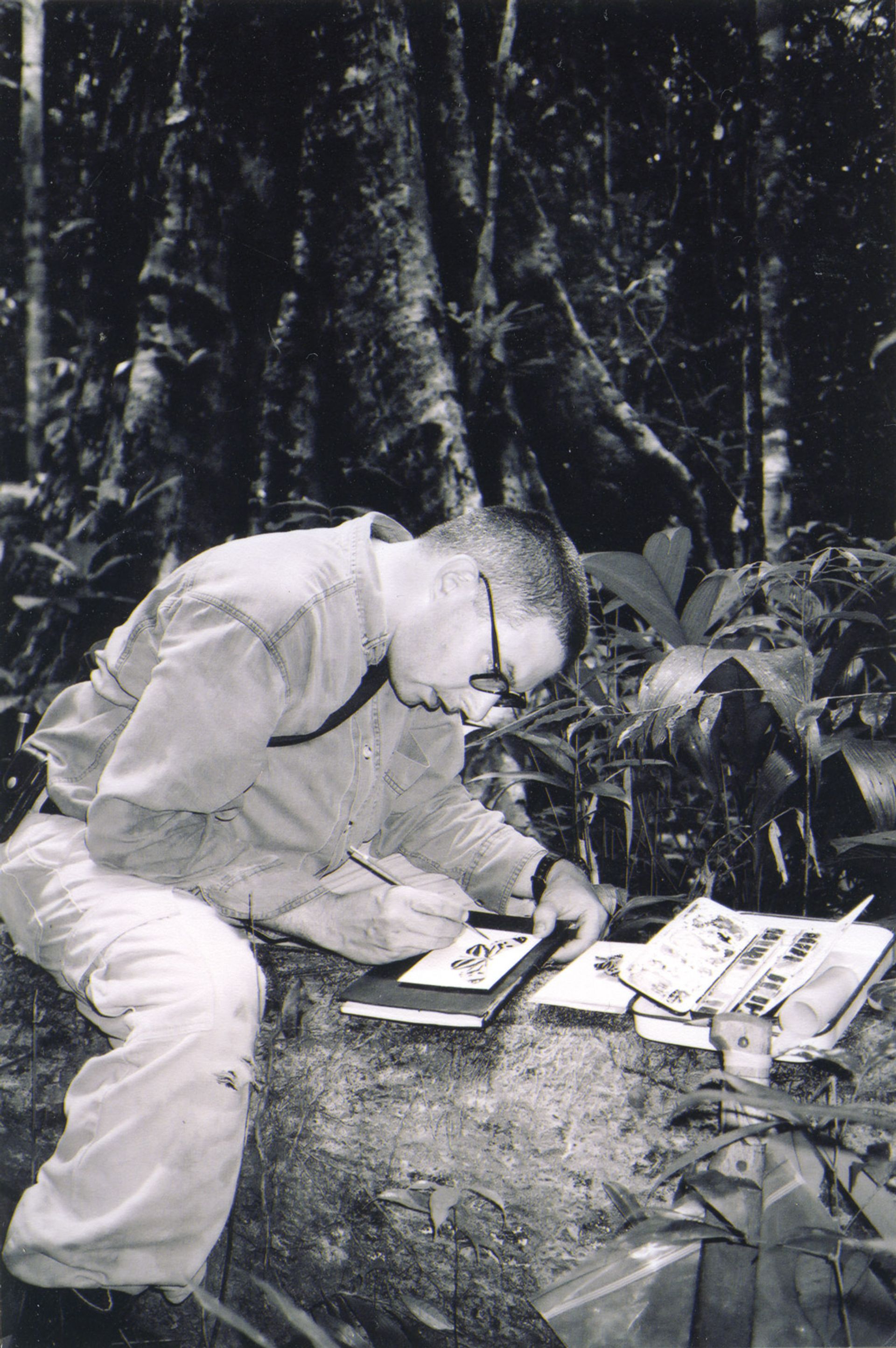

Mark Dion in the rainforest of Guyana Bob Braine; New York; courtesy of Tanya Bonakdar Gallery

BIOGRAPHY: MARK DION

BACKGROUND

Born in 1961 in New Bedford, Massachusetts, into what he has described as “a working-class background”. He grew up with “almost no access to fine art. I was 18 before I saw my first art exhibition—Chardin in Boston.”

EDUCATION

Dion began to study fine art at New York’s School of Visual Arts In 1982, and participated in the Independent Study Program at the Whitney Museum of American Art between 1984 and 1985. “There, I met many of my best friends, and extremely generous teachers such as Craig Owens, Martha Rosler, Joseph Kosuth, Barbara Kruger and Benjamin Buchloh,” he says. “They were amazingly tough, smart and fiercely protective of us when we needed it.” Between 1986 and 1990, Dion worked as an assistant to Ashley Bickerton, whom he met on the Whitney programme.

MILESTONES

Influenced by the science historian Stephen Jay Gould, Dion realised that “nature is one of the most sophisticated arenas for the production of ideology”. The resulting works—The Extinction Series: Black Rhino with Head (1989) and Concentration (1989)—were shown in Xavier Hufkens Gallery in Brussels, Belgium. Dion consolidated his reputation with shows such as Raiding Neptune’s Vault for the Nordic Pavilion at the 47th Venice Biennale (1997), the Grotto of the Sleeping Bear at Skulptur Projekte Münster (1997) and Tate Thames Dig at the Tate Gallery (1999). Other venues have included the Museum of Modern Art, New York (2004), the Natural History Museum, London (2007), the Palais des Beaux-Arts, Paris (2016) and the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston (2017). He has made permanent installations for the Norway National Tourist Route (2012) and Documenta 13 in Kassel, Germany (2012).