Marina Abramović describes her first virtual reality work, which is being unveiled at Art Basel in Hong Kong this week, as a computer game. But, instead of killing one another, viewers are encouraged to save the Serbian artist from drowning by pledging to protect the planet from environmental catastrophe.

“Close to 92% of video games deal with violence and we see the effects they have on our children. Just look at America—it’s terrifying,” she says. “Kids are shooting other people like it’s a video game, without understanding the consequences. I wanted to trigger a positive attitude.”

In her piece, titled Rising (2017), the viewer encounters Abramović standing chest-deep in a tank rapidly filling with water. She beckons to you to press your hand against hers, which transports you to an Arctic scene where melting ice caps tumble into the sea, sending waves crashing overhead. Viewers then go back to face Abramović and have to choose between committing to save the environment—and the artist from a watery grave—or doing nothing, thereby destroying both.

Abramović says she is also developing an app to keep track of actual pledges made, which might range from turning off the lights to not leaving any food waste to simply respecting nature.

The aim of the project is to raise awareness (Abramović says the title refers to rising consciousness as well as rising water), but it also has a deeply personal origin. “What I am most afraid of is the deep ocean,” she says. “It goes back to when I was six and my father taught me to swim.”

Kapoor’s Into Yourself—Fall sucks viewers into a virtual body Acute Art

“He took me out to sea in a rowing boat and left me in the water,” Abramović says. “I was terrified; I started drowning. But then, through the total panic, I realised that he didn’t care if I drowned. I got so angry that with all my force I swam to the boat, where he pulled me in. I had a survival instinct from a very young age.”

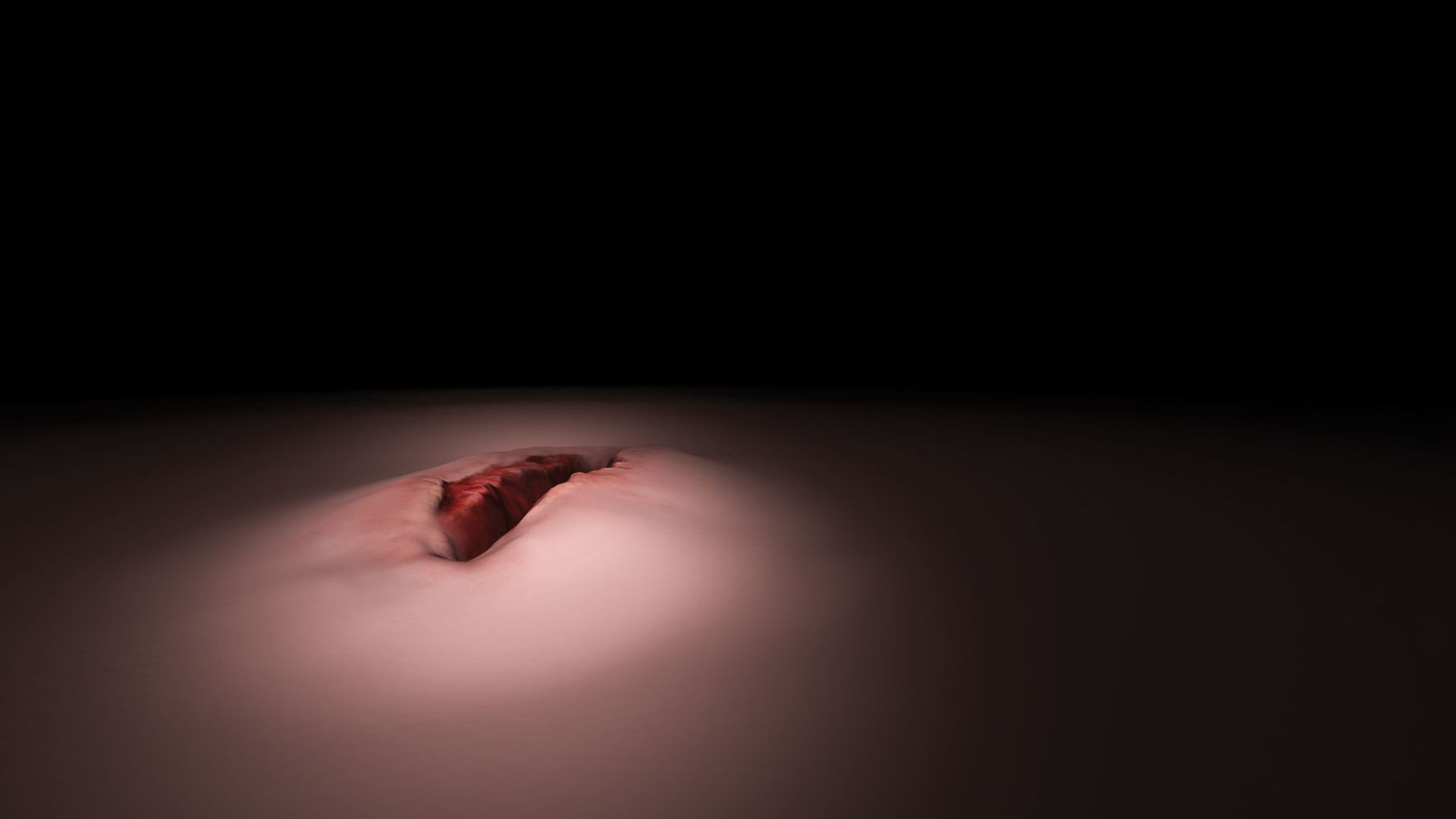

Rising is presented at Art Basel in Hong Kong (ABHK) alongside Anish Kapoor’s first VR piece: Into Yourself—Fall (2017), a stomach-churning experience that sends you tumbling down what appears to be a gullet, eventually spitting you out into meditative deep space or an alternative universe.

Both pieces have been produced in collaboration with Acute Art. One of the first ever VR galleries, Acute Art was founded last year by the Swedish art collector Gerard De Geer and his son Jacob, together with Dado Valentic, a colour scientist who has undertaken projects for Warner Bros film studio. From its base in London, the gallery is working with big-ticket artists such as Jeff Koons, Olafur Eliasson and Antony Gormley, as well as up-and-coming “VR natives” such as Isaac Cohen and Jakob Kudsk Steensen.

The art market is only now beginning to adjust to VR, partly because the medium does not readily lend itself to the standard gallery model. Some artists choose to create limited-edition works; Yu Hong’s She’s Already Gone (2017) is available at the fair in an edition of eight, priced at $100,000 each. Others prefer to make their work available on a range of platforms, for a much smaller fee.

The Acute Art app is free to download, but to access premium content it operates a membership scheme, which costs $29.99 annually. Viewers must also foot the bill for the necessary hardware. De Geer declines to state how many members the service currently has, but says the numbers are growing monthly. Will the gallery go on to sell limited editions? “So far, we haven’t focused on sales,” he says.

The biggest challenge at present, De Geer says, is how to display VR works. “As we tend to exhibit in locations that are quite new to displaying this sort of art, it is often a learning process.”

Anish Kapoor Acute Art

The VR headset manufacturer and content producer HTC Vive, which is Art Basel’s “first official VR partner”, is showing the works by Abramović and Kapoor at a booth at the fair. The Taiwan-based firm also provides hardware and technical support to two galleries displaying VR: Long March Space and Société.

It is the first time that HTC has worked with an art fair, although the company has been partnering with cultural institutions for over three years. It started out working with the National Palace Museum in Taipei and has since collaborated with others, including Tate Modern in London (on its Modigliani show, until 2 April) and the Royal Academy of Arts.

Victoria Chang, the director of VIVE Arts & Culture in London, who is moderating a talk at the fair on 31 March on VR and artificial intelligence, believes that technological developments under way will have a profound effect on the art world.

“VR experiences are getting more and more social,” Chang says. “You can now have multiple users in the same room who can interact with each other physically and virtually, as well as people in different parts of the world in the same virtual space.

“So far, VR experiences in the cultural sphere have been one-person experiences, but I expect that to change very soon. It will be a complete game-changer.”

• Art Basel Conservation, The Singularity: Virtual Reality and Artificial, Saturday 31 March, 1pm

Other VR Works at the fair

She's Already Gone by Yu Hong Courtesy of Long March Space and the artist.

She’s Already Gone (2017) by the Chinese artist Yu Hong follows the life of a female character from birth to old age. The work was created in collaboration with Khora Contemporary, a VR production company established in Copenhagen in 2016. The piece is available through the Beijing gallery Long March Space (edition of eight, priced at $100,000 each). “The work received much public attention when it was shown at the Faurschou Foundation in Beijing,” says Masha Faurschou, a partner at Khora Contemporary, noting that the first edition has already sold to a major Chinese collector.

Timur Si-Qin's New Peace Studio Timur Si-Qin/courtesy of the artist and Société

The Berlin gallery Société is presenting a VR work by the German artist Timur Si-Qin which follows on from his 2016 project to create a spiritual institution and prayer space called New Peace. In the virtual experience, viewers are encouraged to enter his branded “Mirrorscape” world, a mystical state of being that offers fairgoers the chance to see existence “as it is”. The work is priced at $60,000 to $85,000.