A family in the US is seeking the return of a portrait of a late relative that now hangs in a Ukrainian museum, but the country is refusing to cooperate, they say. Their claim has been delayed at while Ukraine’s own efforts to recover its cultural objects looted during the Second World War have stalled.

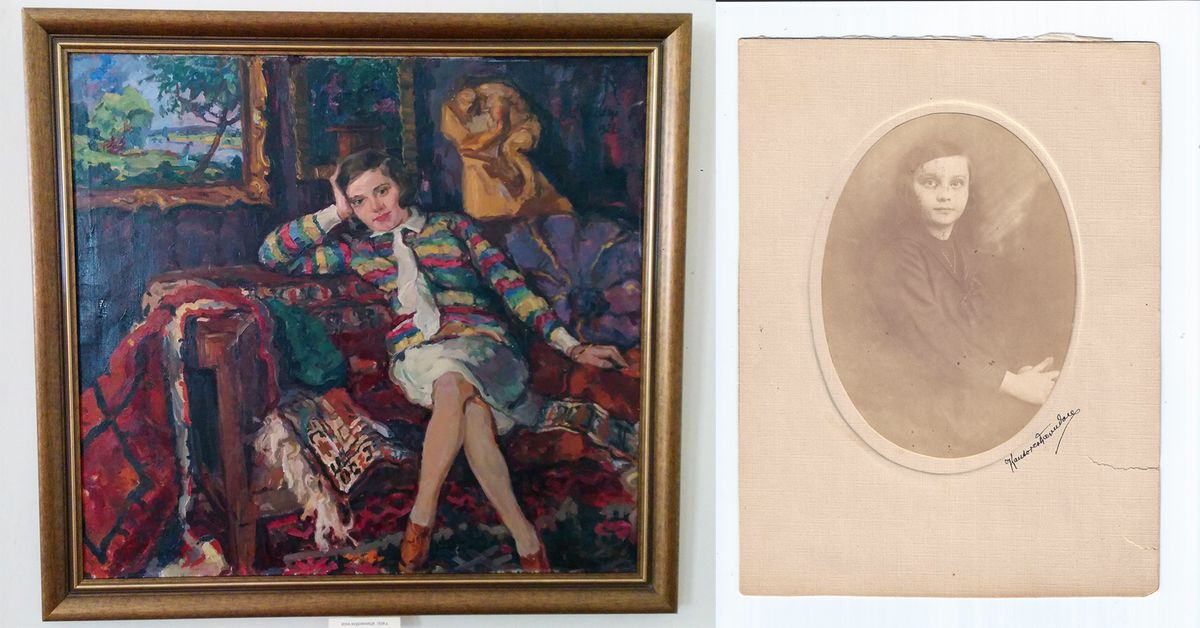

The portrait of a young Magda Mandel (1912-75) by the painter Adalbert Erdelyi (1891-1955) was commissioned by her family in 1928, when the Mandels and Erdelyi lived in the city of Ungvar, then in eastern Hungary. In 1944, under the country’s pro-Nazi regime, Jewish residents like the Mandels were deported to death camps and their homes looted. Magda survived, although her parents did not, and her family never recovered any of their property. Eventually, Magda found relatives in the US who helped her settle in New York, where she married and changed her surname to Shapiro.

After the war, the victorious Soviet Union expanded the borders of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic to include Ungvar and its surrounding territory, and the city was renamed Uzhhorod. In 1948, the Transcarpathian Art Museum was established there and Erdelyi sold his painting of Magda to its collection. But evidence suggests that Erdelyi got the picture from Hungarian looters who were assigned to empty Jewish homes; one of those looters had been his pupil. The painting was never displayed outside the Mandels’ home before it was sold.

“It belongs to us,” says Martha Shapiro, Magda Mandel’s daughter, of the portrait. “There was nothing left of that family—and it’s my mother.” The painting (valued at $25,000-$50,000) was spotted in the museum by family members a few years ago and they asked for the work to be returned. The museum’s director resisted, the family says, despite being shown the Mandels’ documentation of the work and a photograph of young Magda that resembles the girl in the portrait. The picture has now been removed from view, the family says.

Ukrainian government officials have been unresponsive to the Mandels’ claim, they add, although the country has signed international agreements that condemn the pillaging of culture during war. Ukraine also hosted a conference on the restitution of Nazi-era loot in 1996. “Since then, we’ve seen almost nothing from them,” says Thomas Kline, one of the Mandel family’s lawyers. “You can be transparent, or you can stonewall,” Kline says. “The Russians are getting away with stonewalling. Does Ukraine want to go that way?”

“We hope Ukraine’s leaders decide to join with the other countries making efforts to return looted art to its rightful owners,” said Irina Tarsis, the lawyer leading the family’s claim.

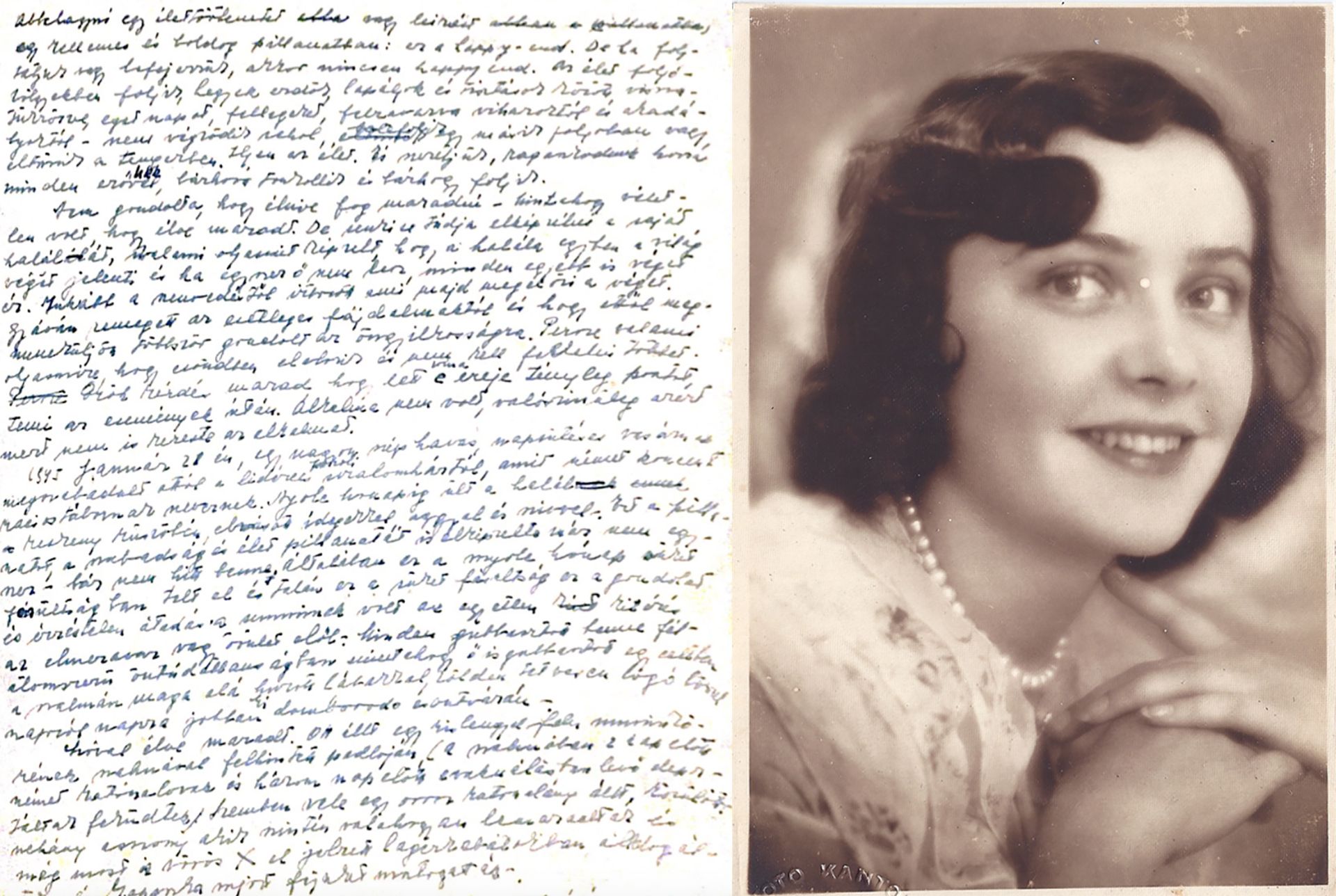

A page from Magda's diary, soon to be turned into a memoir

Meanwhile, Ukraine’s own efforts to recover the many works of art pillaged by the Nazis have stalled. “Two thirds of the art loss of the Soviet Union was from Ukraine,” says Patricia Grimsted of the Ukrainian Research Institute at Harvard University, who is due to discuss the subject with Tarsis during a panel on 13 April sponsored by The Lawyers' Committee for Cultural Heritage Preservation in Washington, DC. New research details shipments of art looted from Kiev by Erich Koch, the Nazi leader in charge of East Prussia and the commissar of Ukraine. Some of those hundreds of works were destroyed by retreating Nazi troops. Other works were sent back to Germany. Russian troops also seized Ukrainian art from Konigsberg (now Kaliningrad) and other locations.

Specialists say much of that work is now sitting in Russian museum storerooms, although some objects have resurfaced abroad. For example, a painting by the early 18th-century French artist, Jean-Pierre Goudreaux (1694-1731), traced back to the collection of the Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko National Museum of Art in Kiev, was consigned for auction at Doyle in New York in 2013. It was removed from the sale after the Art Loss Register flagged its provenance and Doyle informed Ukraine, but the country has made no move to recover it. The picture is believed to be at the auction house still.

Ukraine’s ongoing military conflict with Russia creates another problem. Objects seized by Soviet Trophy Brigades at the end of the Second World War and placed in museums in eastern Ukraine are no longer under the authority of Kiev, since Russia seized those territories in 2014. This includes more than 70 paintings originally from the Suermondt-Ludwig Museum in Aachen, Germany that are now stuck in a diplomatic no man’s land in the Simferopol Museum in Crimea. The German museum was in negotiations to have five of those works returned when Russia sealed off that area. “Things were almost settled, and then we would have had a precedent to talk to other Ukrainian museums,” said Peter van den Brink, the Suermondt-Ludwig Museum’s director, who is also speaking on the Washignton, DC panel.

Crimea’s outlaw status creates further complications. Last year, 2,111 objects that were borrowed from Crimean museums for a Scythian exhibition in Amsterdam were returned to Kiev rather than to the separatist region. Dutch officials cited their original contracts with the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture. Russia responded in November by threatening to cancel further art loans to Holland.