The jewellery trade is big business. Jewellery sales at Christie’s and Sotheby’s last year totalled more than $1bn (both auction houses reported sales of around $550m). Collectors, whether buying for pleasure or investment, are swotting up on the field and vying for top-notch pieces. Those keen to add to their collection may be spoiled for choice at Tefaf Maastricht with exhibitors such as Van Cleef & Arpels, Reza, Wallace Chan, Hemmerle, Glenn Spiro, S.J. Phillips, Hancocks and Didier Ltd exhibiting top-notch vintage and contemporary pieces. Ahead of the fair, we spoke to a few specialists about the field.

The Duchess of Devonshire’s Art Deco diamond necklace by Cartier (around 1925) is on Hancocks’ stand

Vintage pieces

The demand for Art Nouveau pieces, last seen in the 1980s and 1990s, is back, says Christie’s jewellery department head, Keith Penton. He has also noticed a growing appetite for “bold and colourful” pieces from the 1960s and 1970s, typified by the designs of Bulgari, which often incorporate contrasting gems in yellow gold mounts. But not all admirers of the period want to “go down the gemmy route”, says Tefaf exhibitor Guy Burton, the bespoke director of London’s Hancocks, which sells vintage as well as contemporary pieces. “Gold jewellery from the 1960s and 1970s by jewellers such as Cartier and Illias Lalaounis has become a big trend. We’re being asked about this almost more than anything else,” he says. Meanwhile, period pieces by Van Cleef & Arpels and Cartier (London dealer S.J. Phillips is bringing several Cartier pieces to Tefaf, including a pair of fan-shaped aquamarine earrings) and original jewels by Suzanne Belperron and René Boivin continue to be favourites.

A good provenance, particularly a royal or celebrity one, always helps to peak a collector’s interest. Sotheby’s worldwide chairman of jewellery, David Bennett, says the auction house’s noble jewels sales experienced a 64% growth from the dedicated sales launch in 2007 to 2016. Securing the sale in 2012 of the Beau Sancy—a 34.98 carat diamond Henry IV of France gave to his wife Marie de Medici in 1610—for CHF9m was a major coup for the auction house in this niche market. At Tefaf, Hancocks is offering the late Deborah Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire’s Art Deco diamond necklace by Cartier (around 1925; price on request).

Sonia Delaunay’s Danse: Rythme sans fin (1979), on Didier’s stand

Art on your sleeve

A decade ago, if you told a collector they could wear a Lucio Fontana around their neck, many would have laughed. Interest in artists’ jewellery has grown by leaps and bounds in recent years, says the London specialist dealer Didier Haspeslagh of London’s Didier Ltd. “There is a huge community of art lovers who recognise each other by their jewellery. It signifies that they belong to a very exclusive club,” he says, adding that he exports to the US 80% of the pieces he sources in Europe.

There is a huge community of art lovers who recognise each other by their jewellery. It signifies that they belong to a very exclusive clubDidier Haspeslagh

So why did this aspect of Modern and contemporary artists’ oeuvre elude collectors’ attention for so long? Often pieces were made for friends and so have largely remained in private collections, says Karine Lacquemant, the curator of From Calder to Koons, Artists’ Jewellery: the Collection of Diane Venet at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris (7 March-8 July). Alexander Calder carried wire in his pocket and made jewellery during casual conversations; he is thought to have made around 2,000 pieces, says Haspeslagh, who is bringing a 1960s gold brooch by Calder to Tefaf (£50,000). His stand is themed around the Museum of Modern Art in New York’s 1967 exhibition of artists’ jewellery and will include pieces from that ground-breaking show. Jewellery by Calder, Picasso and Dalí are particularly prized, he says.

This diamond, ebony, iron, silver and gold bangle is from Hemmerle’s special 125th anniversary collection, which will debut in Maastricht Bernhard Rampf

The jeweller’s workshop

How does a jeweller keep a goldsmith in their employ for 30 years? “Keep the job interesting and challenging,” says Christian Hemmerle from the eponymous fourth-generation German jewellery house, which is celebrating its 125th anniversary this year. (The company’s former work master is in his 70s and although semi-retired, he still comes in to set the really big gems.) “We want to create one-of-a-kind jewellery that hopefully will be displayed one day in the world’s museums,” he says. “We’re happy to create and push boundaries year on year, which is quite a challenge.”

Hemmerle’s innovative designs pair quality gems (sometimes set backwards to create a spiky effect) with often-overlooked materials such as wood and iron. In 2016, the company released its [AL] Project collection, in which gems are mounted in anodised aluminium settings. So far, their craftsmen have developed more than 25 different colours of aluminium, from sky blue to crimson. To mark the firm’s anniversary, Hemmerle has gone back to its roots as a medals and orders maker to the Bavarian royal family and has created a collection based on designs found in its archive. The collection will debut in Maastricht. Hemmerle does not disclose prices, but auction results over the past five years show that pieces go for between $10,000 to almost $850,000—the latter being for an 8.8 carat diamond ring sold in 2016 at Sotheby’s in Geneva for quadruple its low estimate.

One of the backbones of its 22-strong Munich workshop is its apprenticeship programme, Hemmerle says. The atelier currently has three apprentices who train for three-and-a-half years under a head work master. After two years they can begin to create pieces for customers and by the end of their training they should be able to make a piece from sketches drawn by the Hemmerle family. “We invest in our people,” Hemmerle says, explaining that they educate with an eye to keeping the trainees after their apprenticeships. “It’s important for it to be a passion and not just a job,” he says.

Designs are distributed according to one’s aptitude and a single goldsmith works on a piece from start to finish; if it should later need to be repaired, it goes back to the original goldsmith. “If we give the ideal piece to the ideal craftsman, the outcome will be better and that is our ultimate goal than rather to think from a marketing or commercial point of view,” he says, adding that production is not dictated by the fairs coming up. And how long does a goldsmith have to work on a piece: “There is no time limit. It takes as long as it takes, says Yasmin Hemmerle.

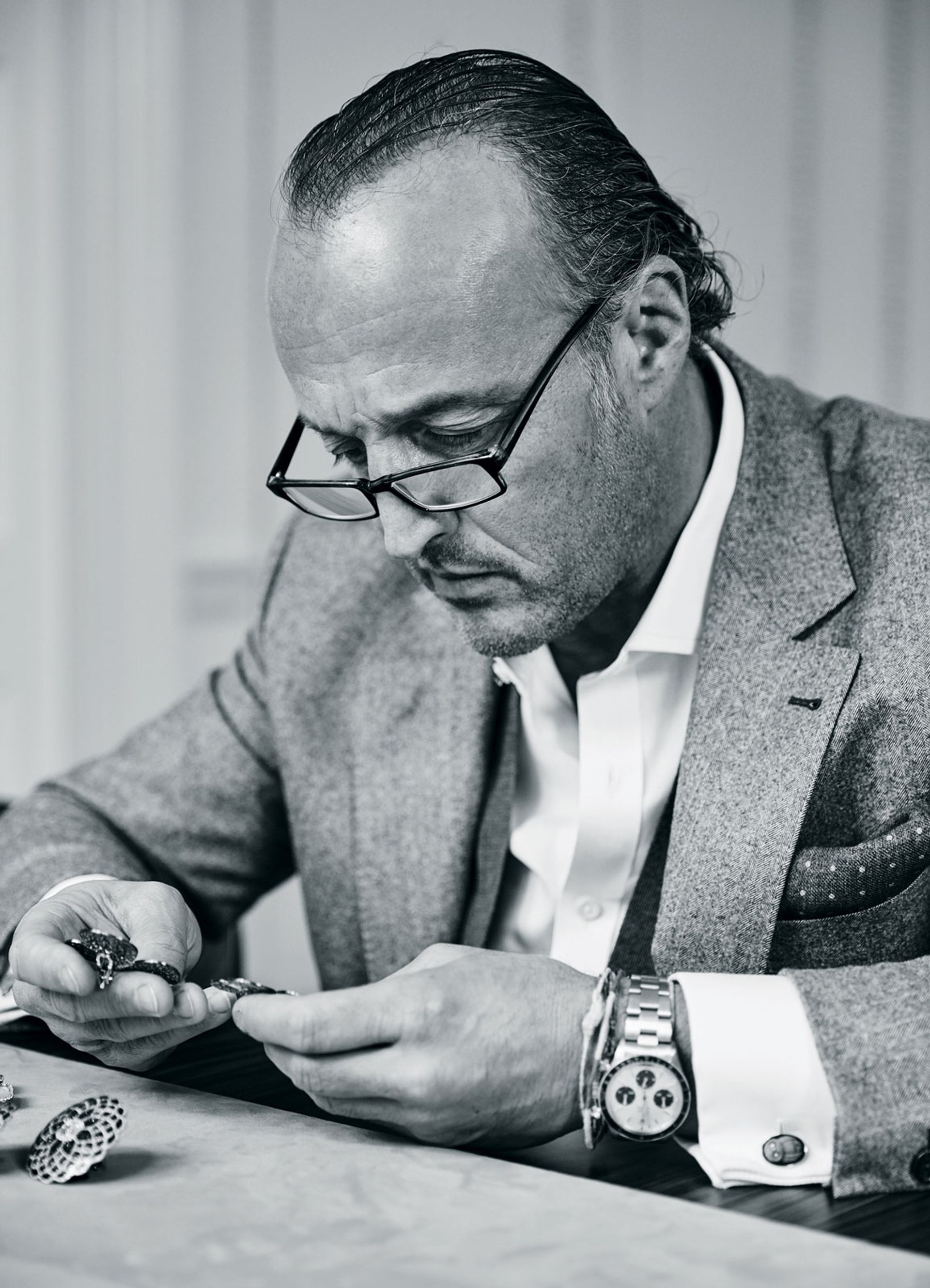

Glenn Spiro is taking his house of G to Tefaf for the first time.

New ‘kid’ on the bejewelled block

After 25 years of selling his one-off pieces to some of the biggest jewellery houses in the business, Glenn Spiro decided to set up shop and trade under his own name. In 2014, he established G and, in 2016, moved his atelier to a space in London’s Mayfair formerly occupied by Queen Elizabeth’s couturier, Norman Hartnell. In four short years, the house of G has become a force to be reckoned with in a very select industry. Case in point: Arnaud Bamberger, the former director of Cartier, recently joined as honorary chairman.

The truth is, if I love [the gem], I’m going to buy it, so I try not to see too much because I fall in love very quicklyGlenn Spiro

G is making its debut at Tefaf Maastricht this month. Prices for his jewellery start at around $40,000 and go up to the tens of millions. Spiro says his pieces “stand alone” and have “personality, style and wear-ability”. Whereas many houses start with a design, 99.9% of the time Spiro starts with the gem. Although the gem takes priority, he does not seek them out because he finds the good ones just too hard to resist: “The truth is, if I love it, I’m going to buy it, so I try not to see too much because I fall in love very quickly.” And who are his customers? “A woman who has the confidence to buy what she likes, not what she thinks she should like,” Spiro says. The Art Newspaper understands that one confident customer, a celebrity out to run the world, is donating a piece to London’s Victoria and Albert Museum.

House of G: gold bangles set with carnelians, diamonds and precious stones