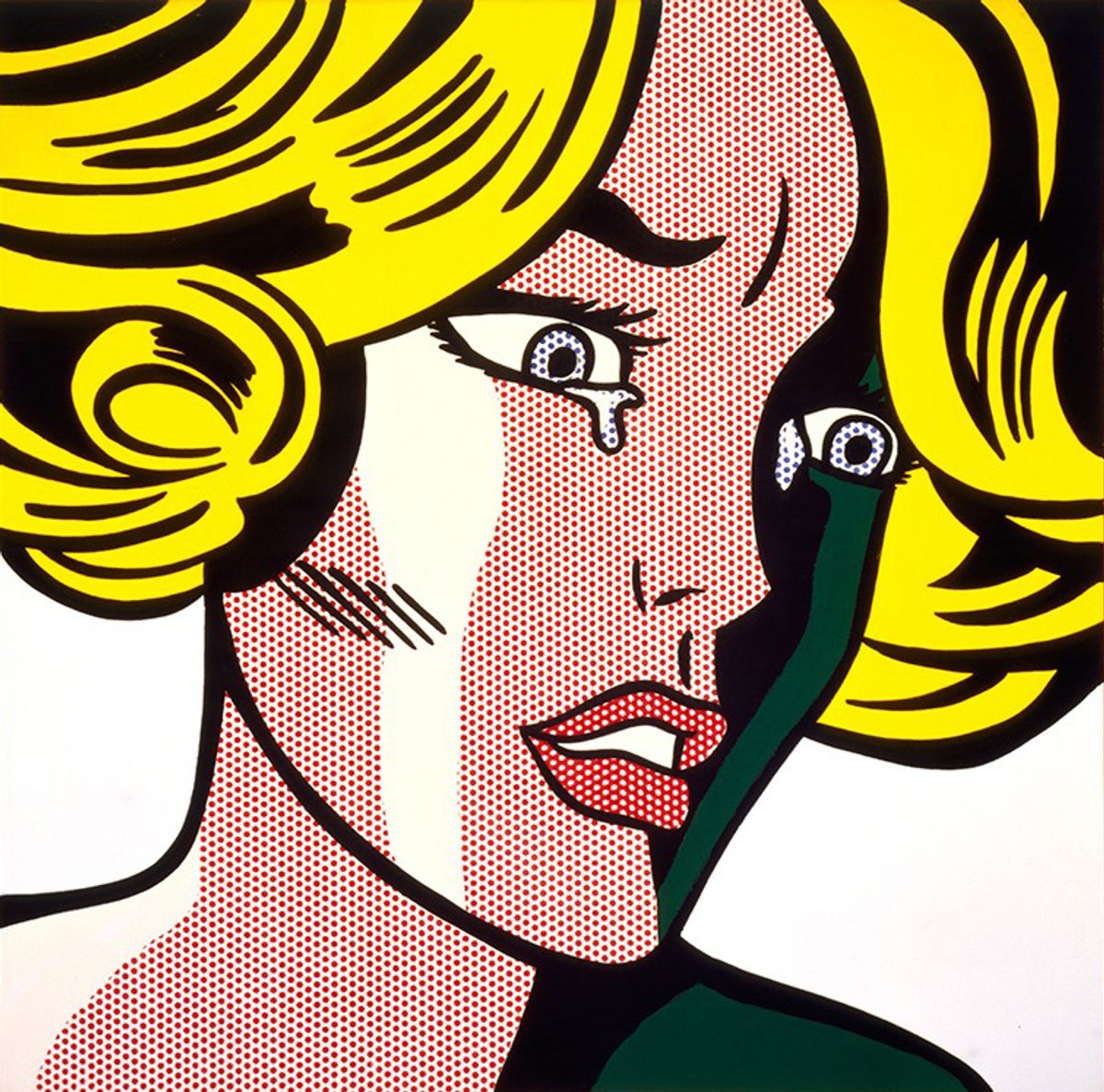

Roy Lichtenstein’s Ben Day dot painting of a fear-stricken woman is going on show for the first time in 25 years in London next month. Frightened Girl (1964) has been tucked away in a private collection in Europe since its last outing in 1993 when it was shown in the US pop artist’s retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

The work is the centrepiece of an exhibition at the newly expanded Lévy Gorvy gallery devoted to three artists who used the Ben-Day dot: Lichtenstein in the US, Sigmar Polke in Germany and Gerald Laing in the UK. All three adopted the printing technique in the early 1960s, although it is hard to pinpoint exactly who took it up first.

“I don’t think there was a first,” the gallery’s co-owner, Dominique Lévy, says. “One of the most striking things about the exhibition is just how international the art world was back then. Polke was much closer to Lichtenstein than we ever thought. There were far less frontiers.”

The Ben-Day dot was first invented in the late 19th century by the US illustrator and publisher Benjamin Day. The cost-effective printing process, whereby dots are rendered in different densities to produce an image, went mainstream in the 1950s and 1960s when it was used to print newspapers, advertisements and pulp fiction comics.

At that time artists were devouring the media for inspiration, both in terms of technique and subject matter. “Lichtenstein, Polke and Laing all came to the decision to use the Ben-Day dot as a vehicle, not because they were looking at each other, but because they were looking at the mass media around them. Particularly Laing, he was seeing posters on the underground and reconfiguring them in his works,” says the gallery’s senior director, Lock Kresler, who organised the first major British Pop art show in London at Christie’s in 2013.

In the Lévy Gorvy exhibition, Source and Stimulus: Polke, Lichtenstein, Laing (5 March-21 April, named after Laing’s 1964 exhibition at the Slade School of Fine Art), two of Laing’s works are to be reunited for the first time since they were created in 1965. Shout and Rain Check, two paintings of bikini-clad women, were sold the same year by the New York dealer Richard Feigen to two different collectors in the US. Neither work has been seen publicly since then.

Images of sexually liberated, coiffed and made-up women were popular among all three artists. Lévy sees this as a celebration, rather than an objectification, of women. “It took a long time to heal after the war and suddenly there’s a new energy,” she says. “With that, there’s a return to figuration after years of Abstract Expressionism. Beauty and desire were back.” The death of John F Kennedy and the Space Race were among the other newsworthy events that permeated the works of all three artists.

Other highlights of the show, of which around a fifth is for sale, include Polke’s Untitled (Couple) (1965-66), which was purchased directly from the artist and has never been seen or published before, and Girlfriends (1964-65), which featured prominently in Polke’s retrospectives in 2014 at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and London’s Tate Modern.