It has been one year since Donald Trump’s inauguration as the 45th president of the United States. In that time, he has presided over a profound degeneration in public life, actively discouraging trust in institutions and belief in the concept of truth, and inciting hatred and division. The art world, a predominantly liberal collective, has reacted with indignation to this degradation of democracy in the US. Many artists profess themselves to be “shocked” and “disgusted” by the new political reality. But beyond these individual expressions of outrage, how has Trump affected the art they are making?

Some say that they have been “paralysed” since Trump took office, finding it hard to work at all. In the past year, Brooklyn-based Fred Tomaselli has “consumed record amounts of news through print, radio, internet, TV, late-night comedy and beyond. It’s a sickness and it’s making me less productive. Trump is the parasite that won’t stop sucking on my brain stem,” he says. Tomaselli first started incorporating pages from the New York Times in his art more than a decade ago, but this source material now has renewed relevance, he says, as the press is “the only institution still holding Trump and his collaborators accountable for their lies”.

Trump is the parasite that won't stop sucking on my brain stem

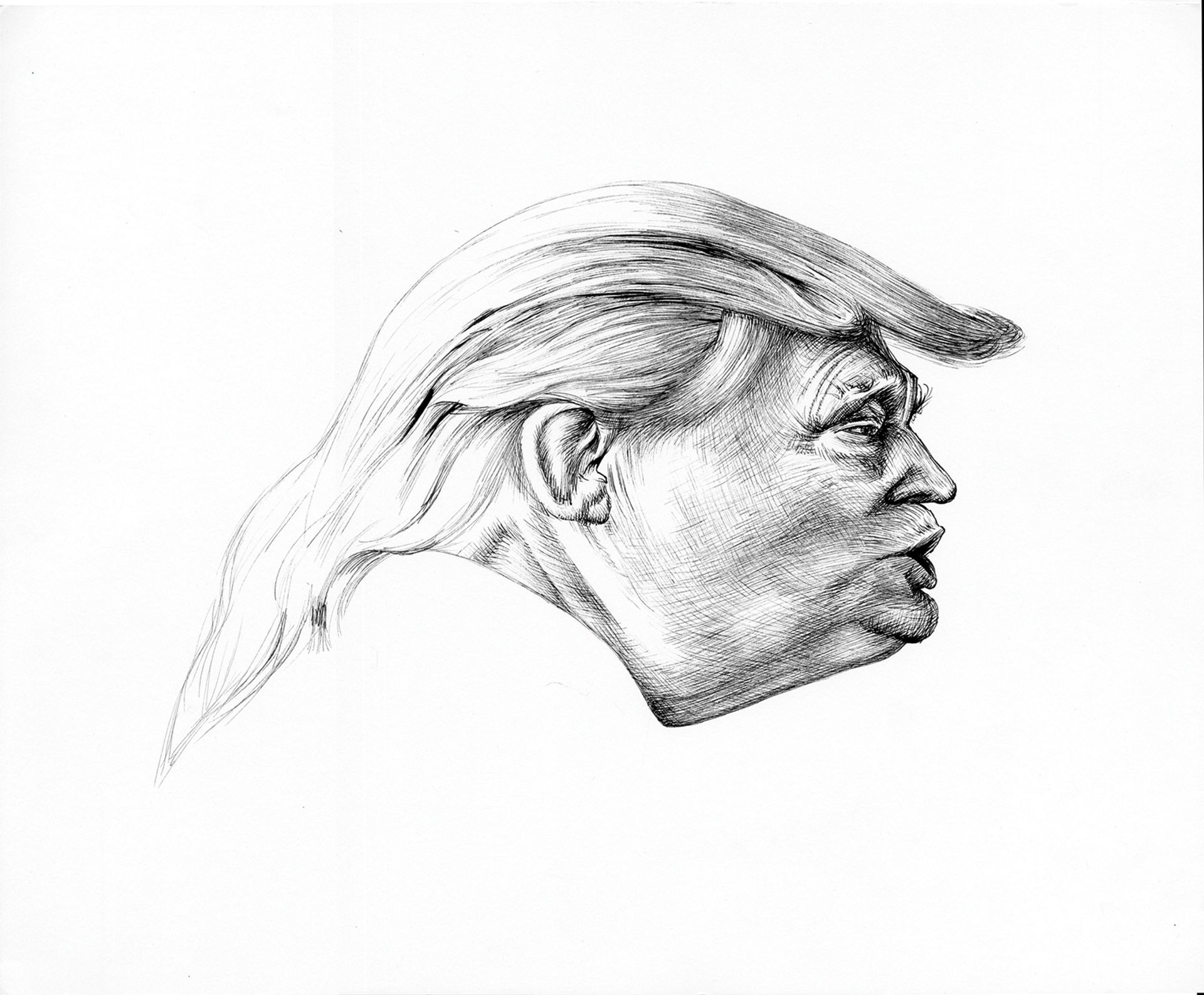

Many artists say that they now feel impelled to make work that expresses their sense of dread. “I feel as though we must, as individuals, state our dismay before the fascist wave overwhelms us,” the Los Angeles-based artist Jim Shaw says. A series of his black-and-white caricatures of Trump, which depict the president in grossly distorted poses, are on display at Metro Pictures in New York (until 9 January), alongside “Neo- Abstract Expressionist” paintings that show the commander-in-chief “smeared in and out of recognisability”. The work is vicious and very, very funny. “I have no illusions that the power of ridicule in the halls of the coastal elites will have any real-world impact, but it seems that it’s the least I can do,” Shaw says, adding that beyond art-making, those who oppose the president need to ask themselves difficult questions. “Trump is a symptom” who represents a “problem of the culture as a whole”, he says. “All of us progressives will need to do a lot of soul-searching as to how we got to this horrifying juncture, and so quickly.”

Fred Tomaselli’s June 2; 2017 (2017) features his signature use of the New York Times Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York

The New York-based artist Julia Wachtel has spent the past year making “more direct” political work than she ever has previously. She describes her new paintings, on display at Elizabeth Dee gallery in New York (until 20 January), as “distilled poems” on pressing political issues such as immigration and gun control. One canvas, called Sunday Afternoon (2017), shows a tornado racing towards a smiling hamburger waving a US flag. The cartoon figure appears blissfully unaware of the environmental catastrophe that is about to overwhelm him—a reference to Trump’s declarations that man-made global warming is a hoax, Wachtel says.

Another artist now feeling a greater sense of political urgency is the New York-based painter Carl Ostendarp, who has stopped using colour in his work since Trump’s inauguration. He now makes dark grey grisaille canvases that read as mountainous US landscapes with paint dripping through them, “like an entropic image that you can’t clear up”, he says, referring to the social decline ushered in by the new president. “After the election, there was a real sense that Americans were finding out just how fucked up we were; the assaults on journalists and people of colour were extreme,” he says.

Jim Shaw’s caricatures include Trump Distortion #1 (2017) Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York

All the artists who tell us that they have found a new political awareness since Trump took office are white. For some black artists, the current president represents a continuation of, rather than a break with, US history, and many of them are far less surprised by the state of their nation than their white peers. “If you look at the civil rights movement, US citizens had hoses turned on them; women and children were beaten by police officers. How is that radically different to where we are now as a country?” asks Adam Pendleton, whose new video, Just Back from Los Angeles: A Portrait of Yvonne Rainer (2016-17), is on display at the MIT List Visual Arts Center (until 11 February). It features the US dancer, choreographer and film-maker reading texts by Malcolm X and the civil-rights leader Stokely Carmichael, and also includes contemporary accounts of police brutality against black people. “We need to have a deep and nuanced understanding of America now, and America 40, 50 or 100 years ago,” Pendleton says.

At first, taking direct action, not making art, seemed to be the most effective way forward for the Los Angeles-based artist Andrea Bowers. “The first few months after the election, I was at a march, organisational meeting or protest every couple of days, participating and documenting,” she says. The turning point for her came with the #MeToo movement, which began in the wake of allegations of sexual harassment against the film producer Harvey Weinstein. Galvanised by the bravery of women telling their stories of abuse, Bowers returned to making art. “I was determined to push harder and make more acute work. I wanted to step up my practice; I still do,” she says. Now she collects materials at public protests and incorporates them in her work.

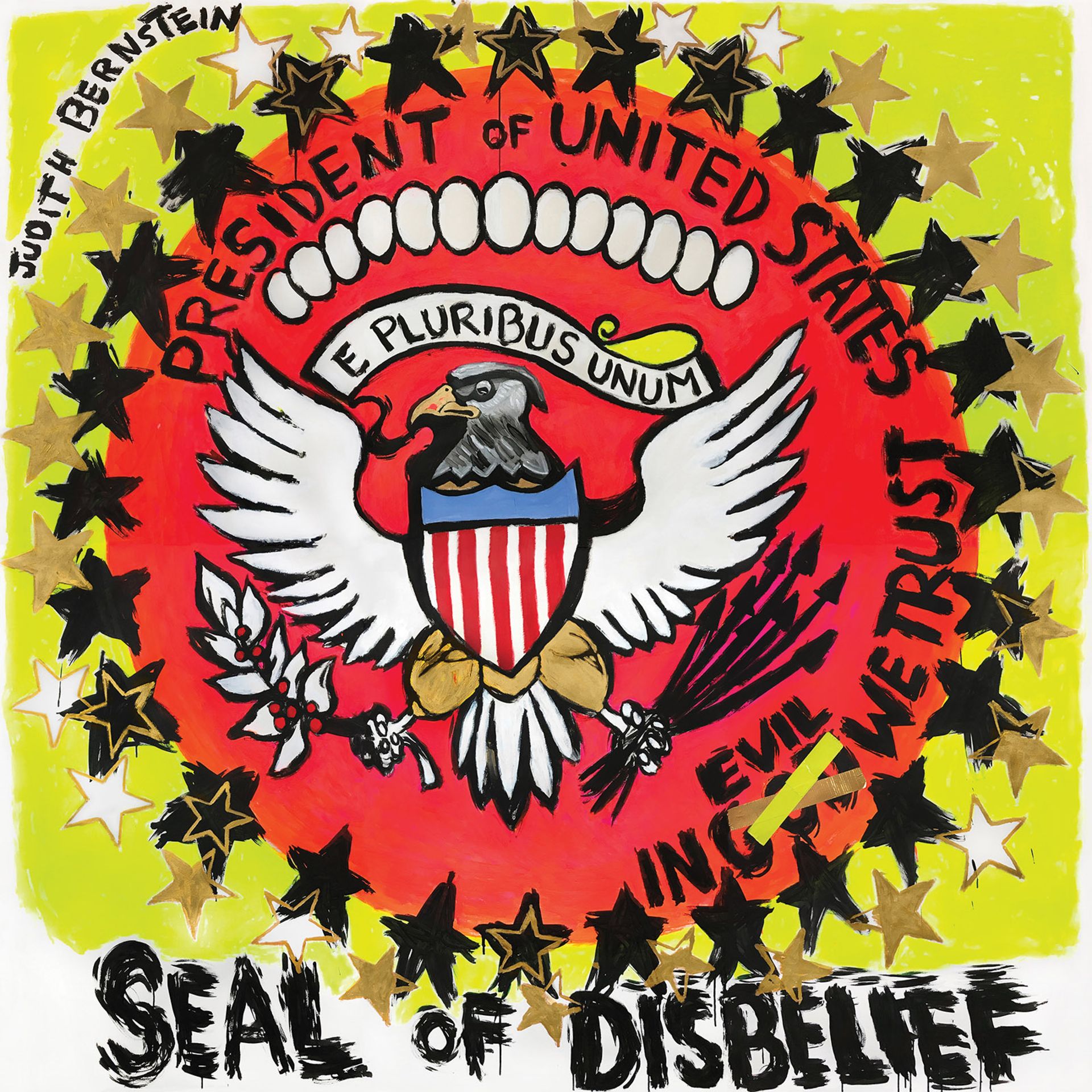

Judith Bernstein’s Seal of Disbelief (2017) confronts the inequities of Trump’s regime Courtesy of the artist

Judith Bernstein, a pioneer of feminist art, says that she is confronting “the very real inequities Trump is advocating”. Her new art is on display in two shows in New York this month; works on paper at the Drawing Center (until 4 February) include Seal of Disbelief (2017), which riffs on the official US motto, proclaiming: “In evil we trust.” Meanwhile, an exhibition due to open at Paul Kasmin Gallery later this month (18 January-3 March) will include seven new anti-Trump paintings. “I am showing [him] for what he is: a fool, a monster, a jester, a sexist, a racist… and a con artist,” she says. Like Bowers, Bernstein advocates direct political action. “Write to your senators and congressman,” she urges. “Be active and go to demonstrations. Run for president, as I will be doing in 2020—vote for Judith Bernstein!”

Showing anti-Trump art to predominantly like-minded viewers in galleries and museums is unlikely to initiate a dialogue with those on the other side of the political divide. But when overtly critical art is displayed in public places, the reactions can be swift and violent, pre-empting all discussion. He Will Not Divide Us (2017) is a performance devised by the actor Shia LaBeouf and the artists Luke Turner and Nastja Säde Rönkkö. Originally consisting of members of the public speaking the words of the work’s title into a live-streaming camera, which transmitted the images online, it was unveiled in New York on the day Trump was inaugurated but was moved after a month following repeated attacks. The work was again targeted at its subsequent stops in the US and the UK. Today, it exists as a flag emblazoned with the words of its title flying from the top of an arts centre in Nantes, France. “In the wake of recent events, in particular those of Charlottesville, where neo-Nazis chanted ‘You will not replace us’ and ‘Jews will not replace us’, the piece’s enduring public show of resistance is more vital than ever,” Turner says.

Much of the art we surveyed for this article is bleak, some of it despairing, reflecting the crisis of conscience that many artists are facing. But for Josh Kline, hope is important. He envisages a “radical utopia” in his video Another America is Possible (2017), which was displayed at Modern Art gallery in London last autumn. It shows a racially diverse group of people burning and burying the Confederate flag, which is “a symbol of slavery, racism and white supremacy in the US. It’s part of a very dark history that the country still needs to confront,” Kline says. “My film offers a glimpse of life in an America that has embraced inclusion, diversity, tolerance and equality—the values that Trump denies.”