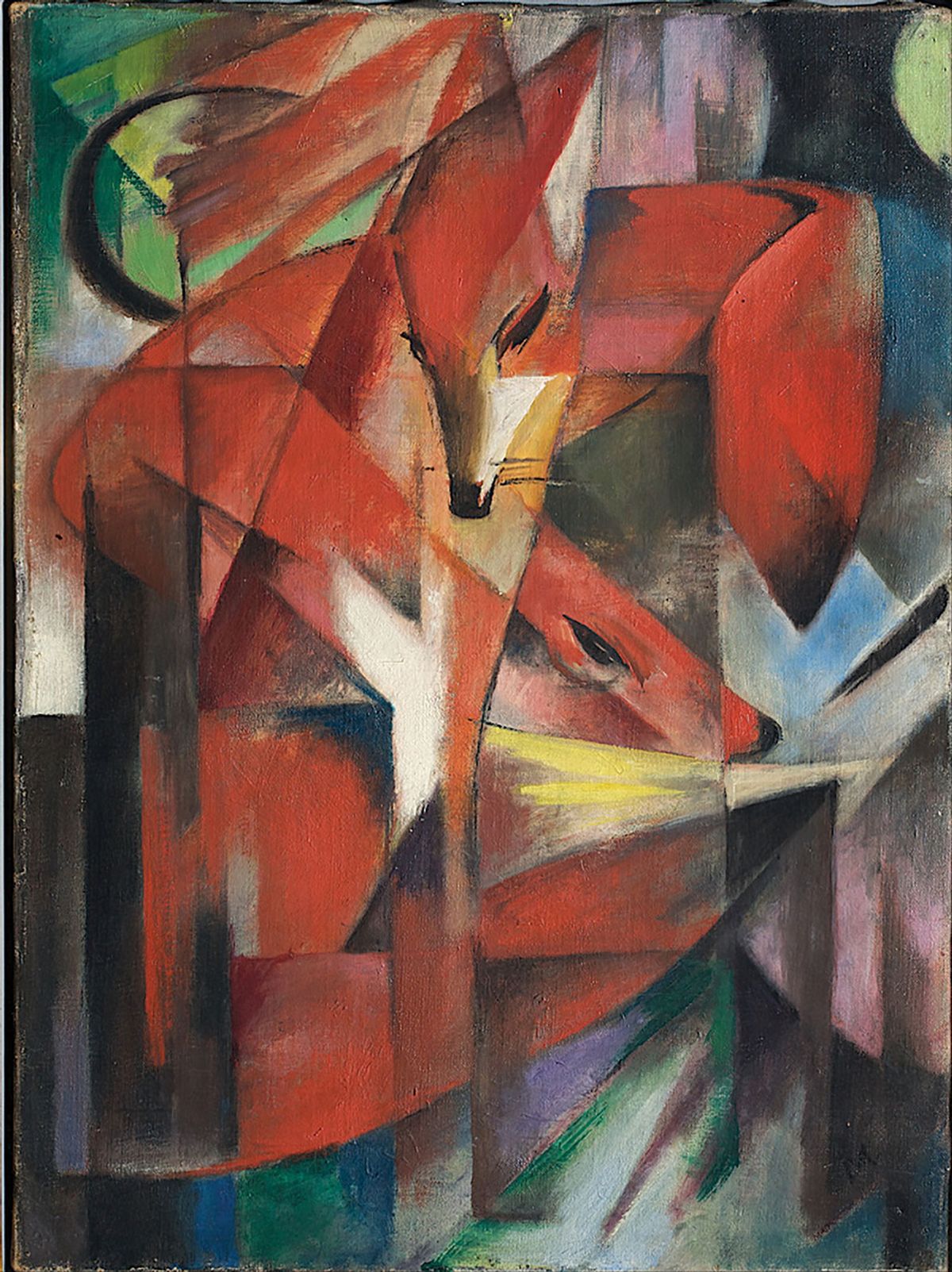

The heirs of Kurt Grawi, a Jewish investment banker who was forced to flee Berlin under the Nazis, are growing impatient with Düsseldorf over their claim for a 1913 painting of foxes by Franz Marc that hangs in the city’s Museum Kunstpalast.

Grawi assembled a small art collection, most of which he was forced to sell in a so-called “Jew auction” at the Leo Spik auction house in Berlin in 1937. Arrested on Kristallnacht, the night of the pogroms against Jews, he was incarcerated in Sachsenhausen concentration camp in 1938. After his release, he emigrated to Chile in 1939. His wife and sons followed him later that year.

The painting by Marc was not among the works in the 1937 auction and is known to have remained in Grawi’s possession until at least that year. It next emerged at the US art gallery Karl Nierendorf in 1939. Extensive provenance research by Düsseldorf has drawn a blank on the details of when and where the painting was sold, and by whom. The heirs argue that the exact circumstances of the sale have no bearing on whether it should be returned.

“My husband's family had to sell everything of value in Nazi Germany in order to pay for the discriminatory and confiscatory charges on Jews and for the costs of their emigration,” says Ingeburg Breit, Grawi’s Hamburg-based daughter-in-law who turns 88 this month. “That is how the painting was lost.”

Germany is one of 44 countries that endorsed the non-binding, international Washington Principles on Nazi-looted art in 1998. In 2009, these were updated by the Terezin Declaration, also endorsed by Germany, which specifically urged that “every effort be made to rectify the consequences of wrongful property seizures, such as confiscations, forced sales and sales under duress of property.”

While the heirs argue that the sale could only have been conducted under duress given the timing, Düsseldorf’s provenance researcher, Jasmin Hartmann, says it could have taken place in the US. Hartmann disputes the heirs’ view that the city is stalling on the restitution of the painting.

“This has been my main focus for the year,” Hartmann says. “But we can’t just give it back. There is too much that remains unclear.”

Hartmann says that Düsseldorf has proposed taking the case to the German government’s Advisory Commission, which mediates and suggests solutions in disputes over Nazi-looted art. But the heirs say they see no need because the case is clear-cut and, given the age of family members, they do not want further delays.

“We have been as patient as possible with the Düsseldorf museum, but it seems they are not willing to do what is simply morally and legally right and return the painting,” Breit says.