“When I arrived in London in 1964, racism was everywhere,” says Rasheed Araeen, whose first career survey opens at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven on 2 December. But it was not until 1969 that the 82-year-old Karachi-born artist, writer and curator encountered institutional racism in the art world.

“I was awarded the John Moores Painting Prize, and then I began my search for a gallery to show my work,” he recalls. “But wherever I went I was met with ‘no’. I couldn’t understand this until I read anti-colonial literature, particularly the work of Frantz Fanon. It was then I became aware of institutional racism, as the legacy of British colonial imperialism.” Fifty years later and little has changed, Araeen says, even though he is now represented by galleries in London, New York and Hong Kong.

One section of the show is dedicated to the artist’s politically charged works from the 1970s and 1980s. The performance piece Paki Bastard (Portrait of the Artist as a Black Person) was created in 1977 when the racial slur was still commonplace. “Things have changed since then, as many artists of non-European origins are recognised and celebrated. But all this is an imperialist game that is used as a smokescreen,” Araeen says. The exhibition also features a previously unseen video of the performance, in which Araeen plays the part of an immigrant worker, who then becomes a victim of street violence, ultimately to be murdered without anyone noticing or caring.

[Recognition of non-European artists] is an imperialist game used as a smokescreenRasheed Araeen

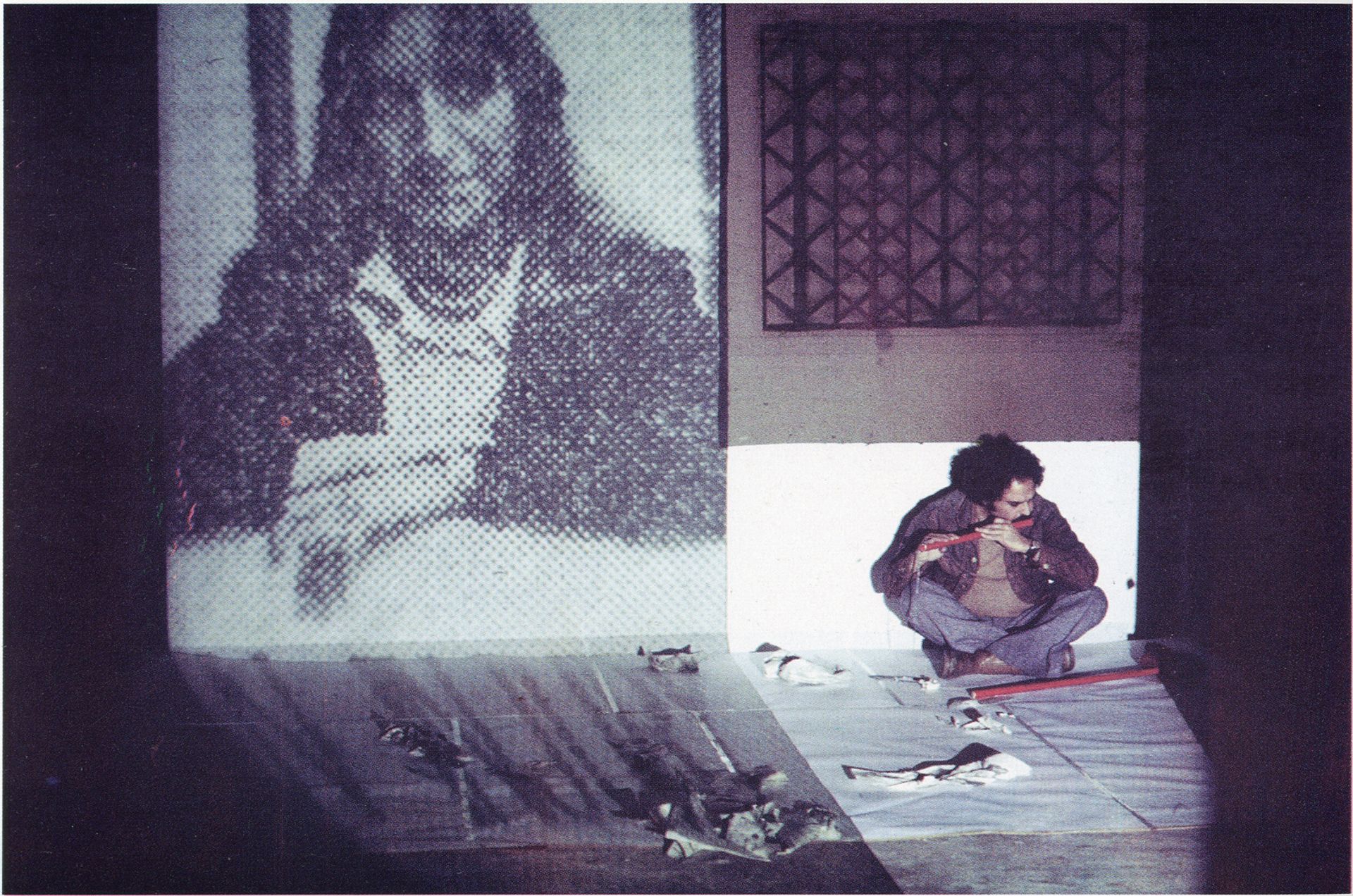

The show includes a photograph of Burning Ties (1975), a performance of Araeen setting fire to five red ties hanging from a stick held over his head. Behind him stands one of his Minimalist lattice works. Nick Aikens, the show’s and the Van Abbemuseum’s curator, describes this as “the destruction of an archetypal bourgeois symbol, of English propriety, of corporate boardroom formality”, but also as “a confrontation with a British art establishment that seemed to have told Araeen that his contribution to Modernism and Minimalism was not valid as each were the domain of white European and American men”.

Another section of the show includes the works the artist created between 1955 and 1964 while still living in Karachi. My First Sculpture (1959) is made of a burned bicycle tyre that Araeen found on a street, twisted into a figure of eight. Araeen says that white privileged views of art history have plagued readings of the sculpture. “Now when critics consider this work, they describe it as ‘Fluxus-like’, even when there was no Fluxus in 1959,” he says. “This is the problem with Eurocentric art history; it legitimises works that can be compared to works it has recognised historically.”

Courtesy of the artist

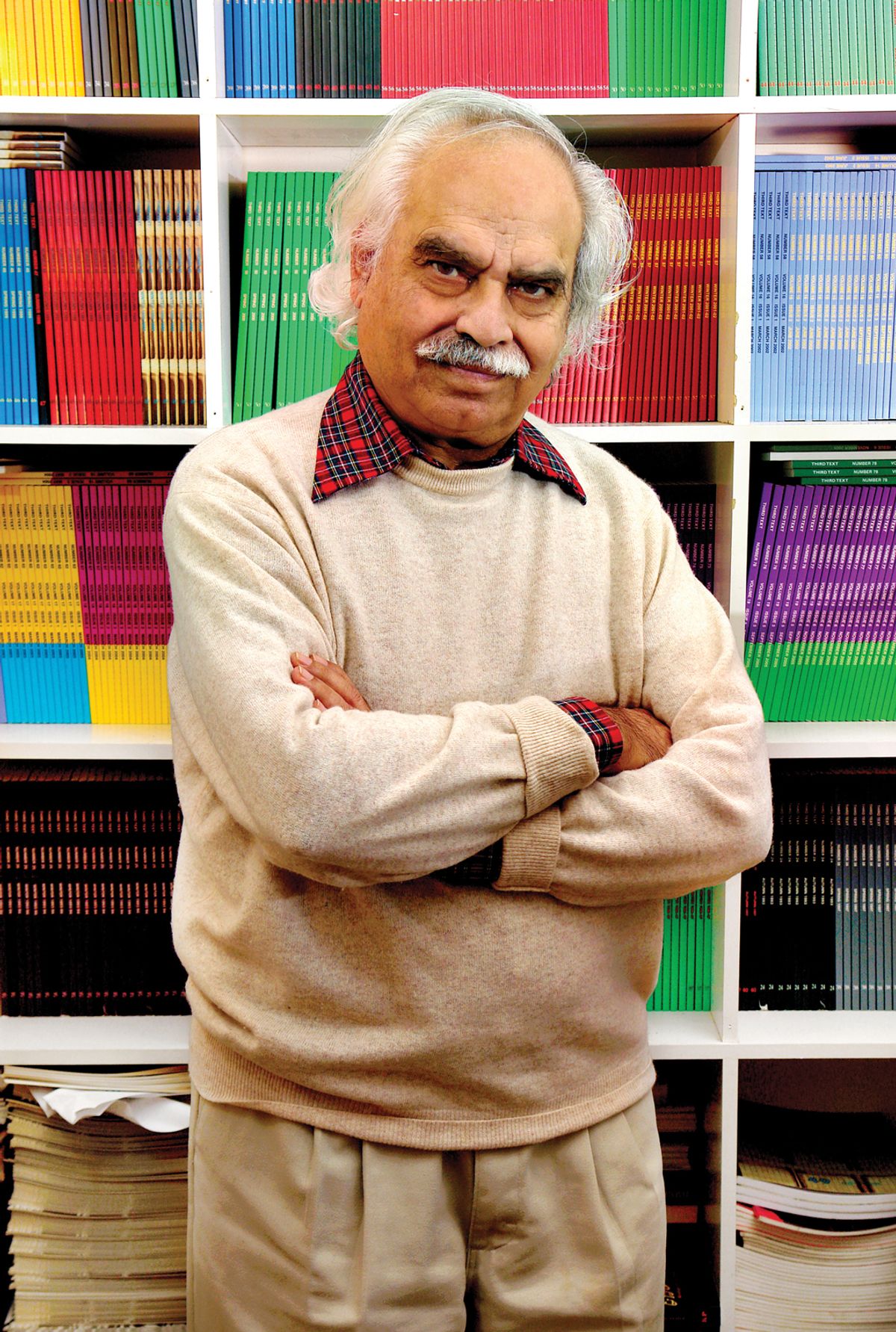

The show’s final section, titled Homecoming, includes the installation The Reading Room (2014-17), comprising copies of the ground-breaking theoretical journal, Third Text, which Araeen founded and edited from 1987 to 2012.

While the Van Abbemuseum show is Araeen’s first comprehensive survey (the museum is also producing an inventory of around 400 works), the artist is beginning to be recognised elsewhere. This year his work has appeared at the Venice Biennale, Documenta, Frieze Sculpture, Yorkshire Sculpture Park and the South London Gallery. The Tate now has his works (and is lending 11 pieces for the show) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Guggenheim in New York and the Pompidou Centre in Paris have also recently started to acquire works.

Araeen’s career survey will not be seen in London. However, it will travel to the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead, as well as the Musée d’art Moderne et Contemporain in Geneva, and the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow.

- Rasheed Araeen: a Retrospective, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, 2 December- 25 March 2018