The seeds may have been germinating for many years, but for the New York-based, Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar, there could not be a more pertinent time to plant The Garden of Good and Evil. Commissioned by the Yorkshire Sculpture Park (YSP), in northern England, as part of its 40th anniversary celebrations, the installation consists of a grove of 101 conifer trees concealing nine prison cells, which refer to the secret “black site” detention facilities operated by the CIA outside the US.

“The US could very well be on the verge of a civil war,” says Jaar, who left Chile for New York in 1982. “I am still under the shock of [the] Charlottesville [riots]; most of the country is. The black sites I refer to in my work are hidden, but unspeakable acts are happening in full view, in front of our incredulous eyes,” he says.

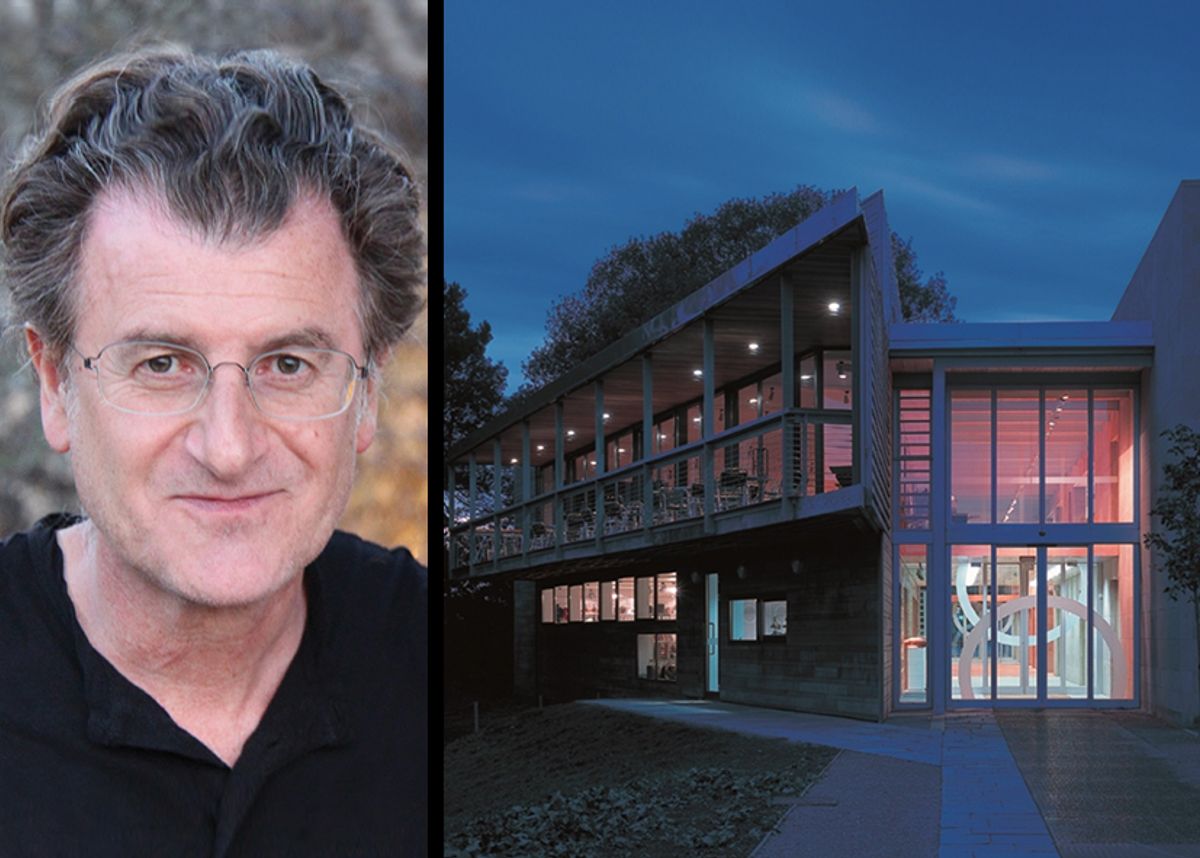

The Garden of Good and Evil is being unveiled at the YSP next month as part of a major solo exhibition by Jaar (14 October-8 April 2018). During the show, the trees will be planted next to the gallery, but thanks to a donation from the London-based non-profit organisation A/political, they are due to be installed permanently elsewhere in the park next year.

“Black sites”

Details are scant when it comes to “black sites”, which are used by the CIA to interrogate al-Qaeda suspects using waterboarding and other torture techniques. Their locations are secret, but reports have identified such prisons in Thailand, Poland, Afghanistan, Romania, Guantanamo Bay and Diego Garcia, among other places.

“The cells are based on what I have read about torture chambers, which contravene all humanitarian laws around the world,” Jaar says. The steel structures range in size from one to two metres high. Visitors will be able to enter the cells and experience the claustrophobia for themselves.

Three existing works by Jaar have been chosen to go on show in the YSP’s underground gallery. A Hundred Times Nguyen (1994) is a photographic installation of a young Vietnamese girl whom Jaar photographed in the Pillar Point refugee camp in Hong Kong in 1991. Jaar decided to include the piece because of its relevance to Brexit. “Immigration has become such an important issue everywhere, but it was a focal point with Brexit,” he says.

The two other works are part of an unfinished trilogy that Jaar is creating using images culled from the media. The Sound of Silence, which was conceived in 1995 but took a decade to realise, is based on a photograph taken in Sudan during a famine in 1993 by the South African photojournalist Kevin Carter.

The famous image of a starving girl bent double with a vulture behind her sparked a furore when it was first published. This was mainly directed at Carter for not intervening to help the girl. Shortly after being awarded the Pulitzer Prize for the photograph, 33-year-old Carter killed himself. Jaar’s piece recounts this story in a series of short texts and ends with Carter’s photograph flashing up on the screen.

Shadows (2014) is based on a image taken by the Dutch photographer Koen Wessing in Nicaragua in 1978. The image depicts the moment shortly after two women learn that their father has been murdered. In his video based on the still, Jaar fades the background to black and renders the women’s figures bright white. The effect leaves their outlines etched on the viewer’s retinas.

Jaar, who describes himself as a frustrated journalist, starts every day by poring over news websites in various languages. He is still searching for the third image in his trilogy. “I have never created a single work from my imagination,” he says. “Everything I have done is a reaction to reality—to give my opinion, or express rage, or discuss certain events poetically. It is my way to understand the world.”