In the entrance, there is the prototype of a leather armchair especially designed for Louvre Abu Dhabi awaiting the opinion of its architect, Jean Nouvel; tall, dressed as usual in black, and surrounded by models of the museum and its dome.

Here he explains his vision for Louvre Abu Dhabi as an Arab city dedicated to culture and the arts, and insists on a more holistic architecture.

The Art Newspaper: In Abu Dhabi, you worked under the best conditions: with a good budget, time and all the space you needed, along with the support of the authorities. Is this project the “ultimate Jean Nouvel”?

Jean Nouvel: I am, of course, happy to see what I hope will be a successful end to such an ambitious and accomplished architectural project, with all of its symbolic dimensions. As other nations have done throughout history, the Gulf countries are keen to mark their present “golden age” with educational and cultural monuments in their new capitals. Our Emirati partners had high standards. I didn’t even know which museum would occupy the site when I started to think about the concept.

The truth is, no project of mine is identifiable by its style. This would not correspond with my intention or my philosophy. My concept of style is an underlying intellectual attitude. I consider architecture as dependent on a context; there are always written and unwritten obligations that do not necessarily correspond with my aesthetic vision.

TAN: How would you define the concept of Louvre Abu Dhabi and its evolution?

JN: It is a museum that requires a certain type of architecture. It is not just a functional building; it has a symbolic and even a spiritual meaning, and I do not mean spiritual in the religious sense.

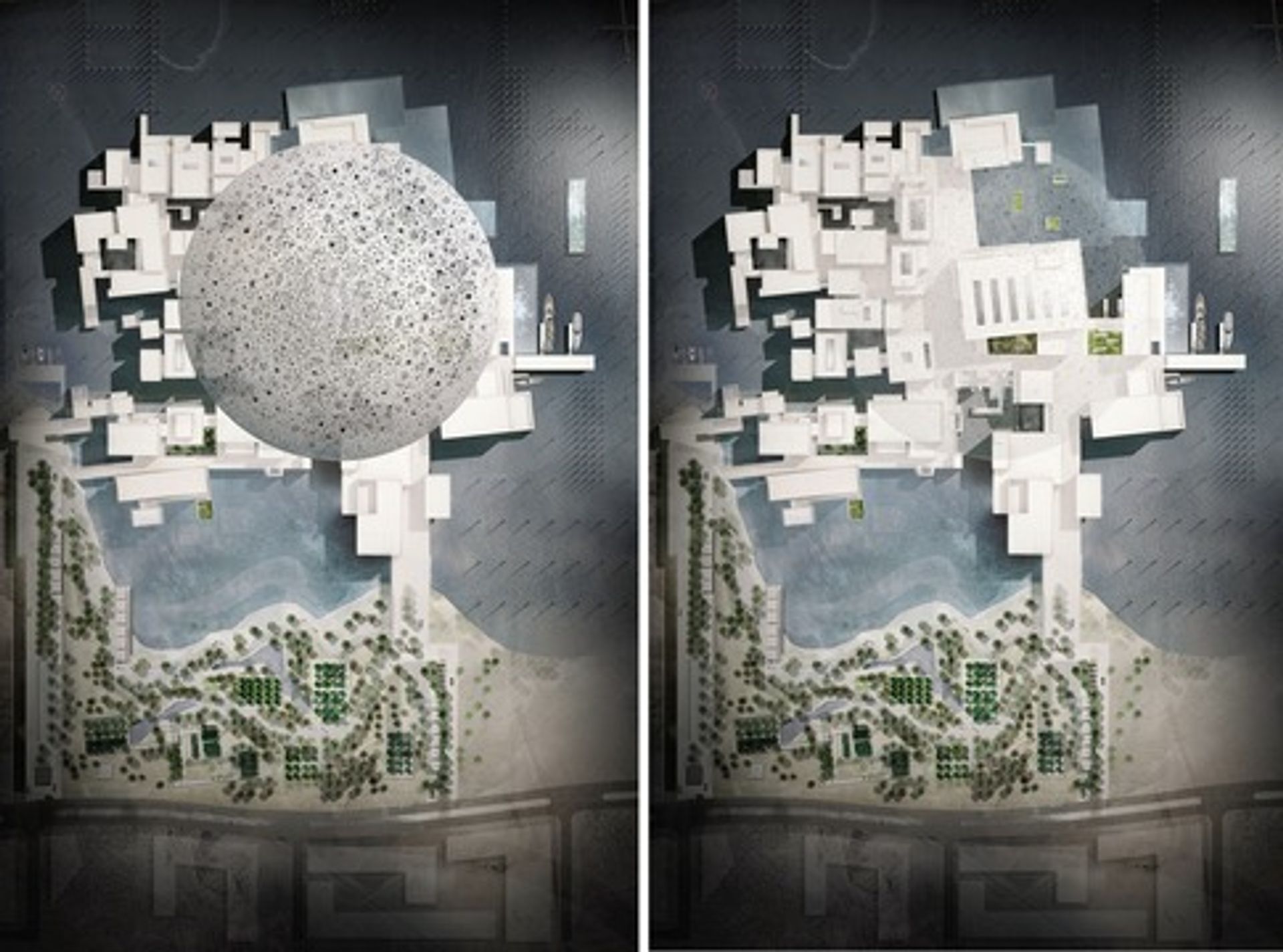

I always wanted the place to be more of a neighbourhood than a building. I began with interconnected blocks of differing proportions, inspired by white Arab cities—the medina. This concept allowed us all the flexibility we needed, but I was never completely free; changes were dictated by many parameters, some self-imposed, others imposed by the situation and the partners. The architecture had to respond to these constraints and fulfill a will and a desire. It’s not architecture for the sake of architecture; architecture has to be connected to ideas, to the spirit of the place.

TDIC, Architect Ateliers Jean Nouvel

TAN: You are also designing the displays; but isn’t this going beyond your role as an architect?

JN: How can you consider a building if you do not think about its content? I am stunned by this spreading schizophrenia—splitting the exterior and the interior of a building. The idea of an osmosis between a building and its content and meaning is fundamental. Architects are increasingly having to face this issue with developers, who often choose one architect for the shell and core, and another for the inside. In this project, I was glad to be able to develop a coherent concept, working on interior finishes and displays in direct relation to, and in harmony with, my building. I introduced the notion of the palace, with specific proportions and materials evolving with the content. We also had passionate and very detailed discussions with the client and the curatorial team to enrich this project with the scholarly and cultural programme.

TAN: How do you apply these ideas here?

JN: It means framing the site, working on connections between the galleries in a museum dedicated to civilisations, where the comparisons and dialogue between works of art should create an emotional shock for the visitor, comparable to the one felt by people when the objects were in their original context. How do we transfer such a feeling in a completely different milieu: that is the fundamental question to be answered when conceptualising links between spaces and the collections. There must also be a way to evoke the context in which the art was originally made and used: for example, this is what I was seeking at the Quai Branly — Jacques Chirac [for the indigenous arts of Asia, Africa, Oceania and the Americas] museum in Paris by evoking the kind of light in the places where the sacred artefacts originated. It is not a reproduction so much as a subtle allusion. What I did not want was a typical Western display on brightly lit, white walls and plinths.

In Abu Dhabi, we also had to take account of a specific relationship with time. I have accentuated and given extra space to the notion and expression of permanence, and we were asked to erect a permanent museum, even though the constitution of a permanent collection is still a work in progress. So we had to consider that any work in the show could be replaced later by a completely different one. This required some flexibility.

Abu Dhabi Tourism & Culture Authority, Photo: Fatima Al Shamsi

TAN: Louvre Abu Dhabi displays some of your most characteristic elements, such as the filtering of light.

JN: Perhaps you can see a formal vocabulary in my work that is the product of my unconscious. If I had an obsession, it would be with light, but each building is of a time and place; it is the product of the will and wishes of a client.

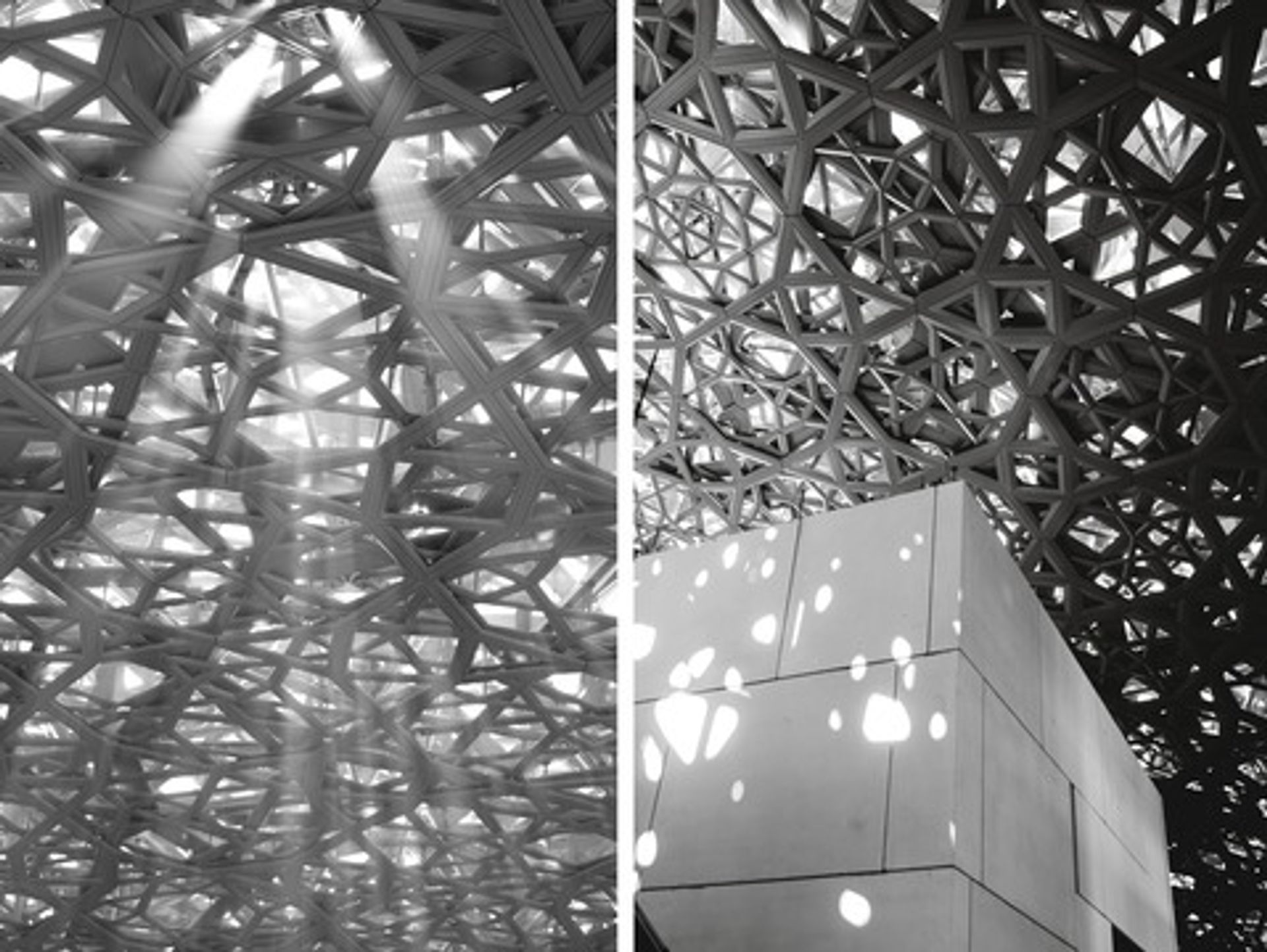

The architect should not impose a colour, technique or material before considering the various options and understanding the deep meaning of the location. This is a museum in an Arab capital, where light and shade punctuate the view, creating their own sense of mystery and culture. In Arab culture, seeing through the filtered light of a mashrabbiya [pierced screen] is very natural.

You have an international architecture that repeats the same reflexes based on the dictatorship of logic. It has a right to exist, but why must it be so generic? In some cases, a building should be conceived with a nature of its own, connected to history and geography and taking people’s desires into account, without any prejudice. It is an alchemy we have to find together. Again, I do not have a set of forms or colours that I want to repeat everywhere; I am an architect, not a painter or a sculptor.

TDIC, Architect: Ateliers Jean Nouvel

TAN: With this in mind, were you seeking to recall the shade of palm trees in an oasis with the dome?

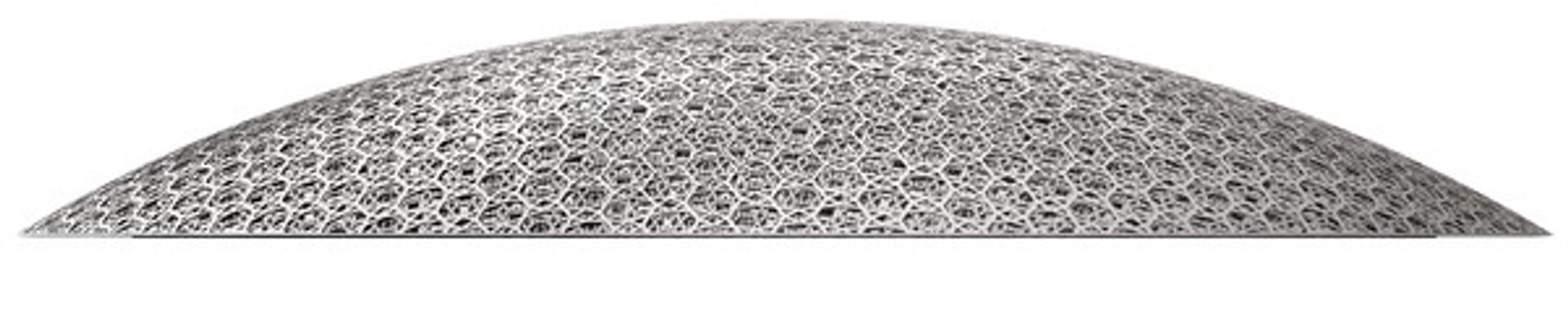

JN: I don’t see it as an oasis. It is a unique object, a drawing, a complex geometry interlacing Arab motifs from a forgotten past. The light is filtered through a layering of four fine domes, creating a spiritual and kinetic cycle. The shade will move constantly throughout the day and according to the seasons. The dome is not exactly white, but silvery, and with time, I hope it will remind us of the colour of sand.

The dome is a parasol, which can be interpreted in various ways. Traditionally, you can let the light enter a dome from the sides, through the lucarnes [slender dormer windows], or from above, through an oculus in the centre. Here the light falls like rain—I think it is a first. I wanted to create a moving relationship between light and water and find a connection with the elements of the climate. This is also why I wanted water in the building, as a reminder of the cooler streets of a city.

Louvre Abu Dhabi is a neighbourhood with its streets, squares and terraces, where the works of art are shown inside the galleries as well as outside. It is also a palace, with palatial proportions; a peninsula, with its own mystery, shaped by light and water, the archetype of a micro-city devoted to a spiritual mission that you can only guess at from the outside and only discover by entering.

• Exclusive: the first interview with Louvre Abu Dhabi’s French director

• Introducing the Emirati woman who is deputy chief of Louvre Abu Dhabi

• The architect of Louvre Abu Dhabi reveals his sources of inspiration