The World Monuments Fund (WMF) is launching a £500,000 scheme to train Syrian refugees living in and around the Zaatari camp on the Jordanian border in traditional stone masonry. The aim is to develop skills so that cultural heritage sites that have been caught in crossfire or destroyed by Isil can be rebuilt once peace is restored to Syria.

Organisers of the training course, which is due to launch in the border town of Mafraq in Jordan in August, are also hoping to recruit Jordanian students in a bid to alleviate some of the pressures put on the local community by the volume of people fleeing war-torn Syria. The project is being developed with Petra National Trust, a Jordanian not-for-profit organisation whose mission is to promote the protection and conservation of the Unesco World Heritage site of Petra.

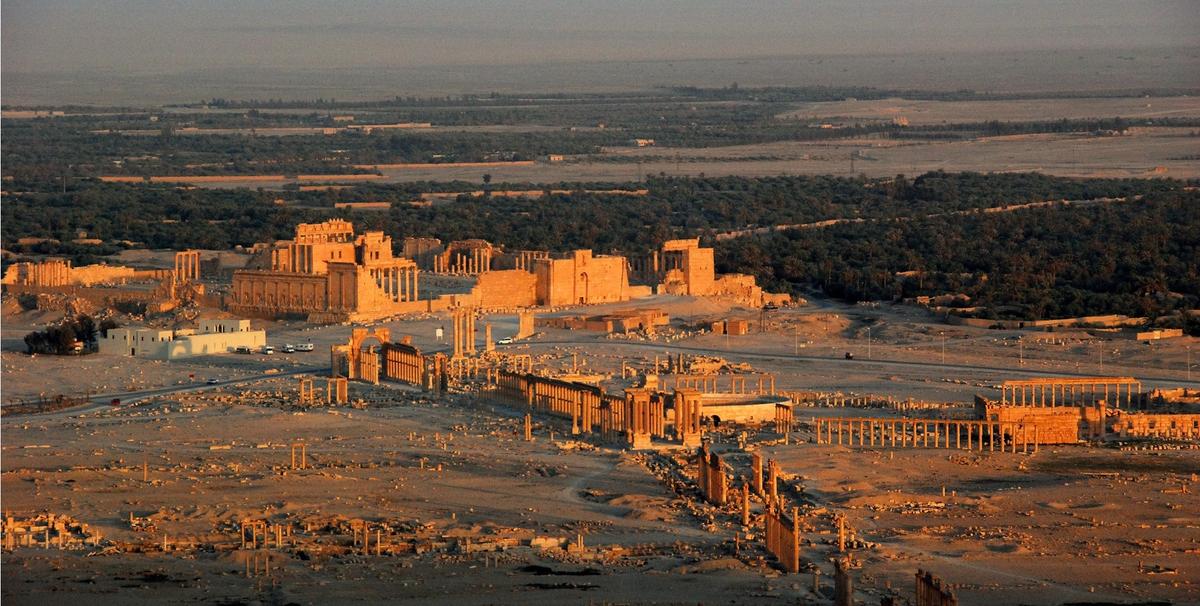

“There has been enormous destruction in Palmyra, Nimrud and Aleppo,” says John Darlington, the executive director of the World Monuments Fund Britain, which is working with the New York-based WMF on the scheme. “When the dust settles, one of the things that will stop restoration is that we will see money going into places like Palmyra but the skills on the ground won’t be there. Because so many people have left, there’s a huge skills deficit.”

There are an estimated 80,000 refugees living in the Zaatari camp, with a further 80,000 thought to be living in the neighbouring towns and villages.

The blueprint for the Syrian project came from a similar scheme begun by the WMF in Zanzibar two years ago. While the Anglican Christ Church Cathedral was being repaired, an intensive programme of skills development was also launched. There is now a pool of local trained stone masons to help with future repairs.

“We are looking for stone masons who are already living in the local community or in the refugee community. It’s a long-held tradition in that part of the world,” Darlington says. “We don’t want to parachute in a load of experts and then leave. The idea is to train people who will become trainers themselves, so it will cascade out.”

With the conflict in Syria raging on, it is too early to say how long the project will last, or indeed when the WMF will be able to start work there. “We are aiming to recruit 34 trainees who will be able to train others,” Darlington says. “If the project is shown to make a real difference, we will be rolling it out elsewhere.”

Since civil war broke out in Syria in 2011, much of the country’s cultural heritage has come under attack, especially in the cities of Palmyra and Aleppo, where historical buildings such as the Citadel of Aleppo and Great Mosque of Aleppo have been either destroyed or damaged.

The scheme is supported by the UK’s Cultural Protection Fund, which was established in 2016 to safeguard monuments and heritage sites at risk due to conflict. Other projects to benefit from the £30m fund include a scheme, led by the University of Liverpool, focused on Yazidi historic shrines in Dohuk, Mosul and Sinjar in Iraq; the creation of a database of cultural heritage on Soqotra, a Yemeni archipelago between Yemen and the Horn of Africa; and initiatives in the Occupied Palestinian Territories including the establishment of a new cultural and youth centre.