Visitors to Art Basel’s auditorium on Friday can expect something of a love-in. In the talk in the fair’s Artists’ Influencers series, hosted by Hans Ulrich Obrist of London’s Serpentine Galleries, it is the turn of the French artist Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster to pay tribute to an inspirational individual. Her choice is Kasper König, who spotted the artist while she was a student and has invited her to take part in various important shows since. But Gonzalez-Foerster’s selection also has huge personal significance for Obrist: König was his mentor, who took the young Swiss art critic under his wing in the early 1990s, and showed him the curatorial ropes.

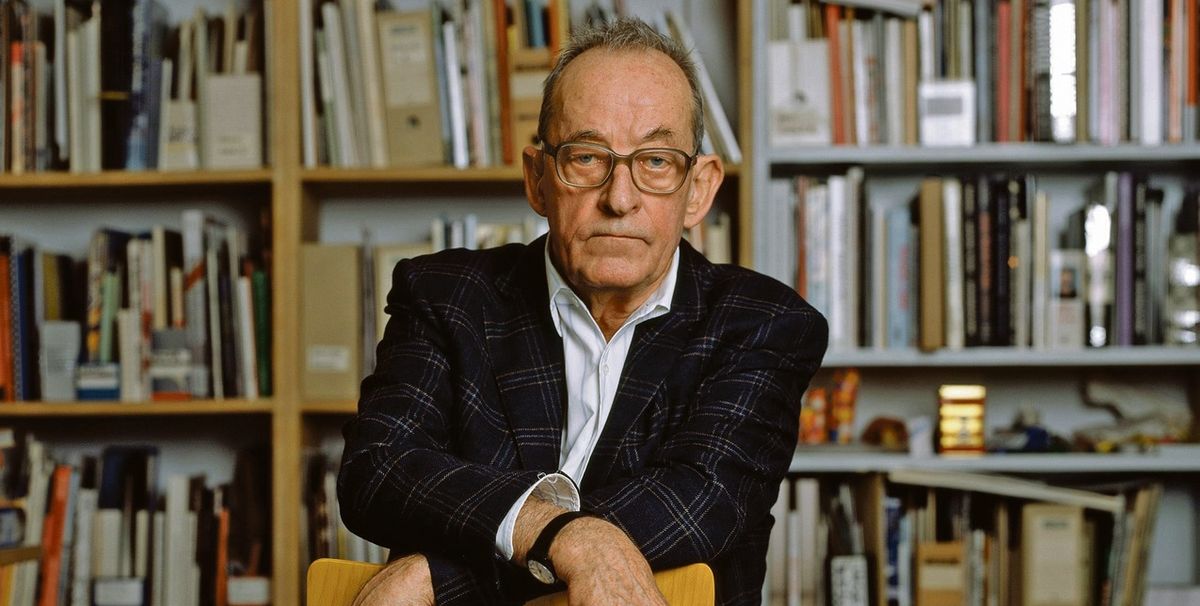

König has been a significant curator for five decades. In 1968, at just 24, he was instrumental in the organisation of Europe’s first museum exhibition dedicated to Andy Warhol, at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, under the guidance of the great Pontus Hultén. He went on to curate or collaborate on numerous influential shows of contemporary art in Germany and beyond, including the surveys Westkunst (1981) and Von Hier Aus (1984). He was a director at that prolific producer of significant artists, the Städelschule in Frankfurt (where he founded the gallery Portikus), and also taught in Düsseldorf and in Nova Scotia. He led the Museum Ludwig in Cologne between 2000 and 2012. But he is perhaps best known for curating the 100-day public art exhibition Skulptur Projekte, held every ten years since 1977 in the north-western German city of Münster. The fifth edition with König as chief curator opened on 10 June (until 1 October).

Gonzalez-Foerster met König in Düsseldorf in 1986 when he was doing a seminar on the Münster project, then about to stage its second edition. A year later he was on the selection jury for a curatorial course at Le Magasin in Grenoble, France, for which she had applied. She says it was important to König for an artist to be among the group chosen, “and this is how I entered this curatorial training”, she explains.

Gonzalez-Foerster’s work has consistently teetered on the curatorial-artistic threshold. Her piece for Skulptur Projekte in 2007, Roman de Münster, reflects König’s idea of the exhibition as an evolving dialogue between the sculptures made for the present edition and the ghosts from previous iterations, whether they have remained in situ or not.

“He is a great inspiration for me,” Gonzalez- Foerster says of König, “and this is what I tried to display in the piece in Münster—a curatorial approach from an artist is a way to relate to that.” The work featured sculptures from previous Münster exhibitions, recreated at 1:4 scale in one of the city’s parks.

“The Roman de Münster is a palimpsest of all the different Münster [editions], but it is also a tribute to this type of invention—an exhibition which happens every ten years, which happens in the city.” Her work was an exemplar of the way she tries to see “the different layers of the exhibition as a context, as a topic. I think for the Roman de Münster, that was very clear.” She adds that she is “super-happy” that “some leftover miniature sculptures” from it will go to Marl, the town close to Münster that is a second destination for this year’s event.

Obrist suggests that König’s keen awareness of artists’ differing sensibilities has been essential throughout his career. “His entire methodology had a lot to do with artists from the get-go. And the Münster project is very much based on that. The lead-up to Münster is a ritual that happens every ten years: he would have these conversations with many different artists all over the world, and then choose some to realise their public art projects.”

Tough, yet sensitive

König’s closeness to artists is illustrated in his own recollection that the US artist Dan Graham was “in a sense, my intellectual and spiritual adviser” for Münster’s first edition in 1977. While Graham declined to propose a work himself, he pointed König in the direction of Michael Asher, promising him that Asher had “a completely different sense of space and time, because he is from California”. Asher proposed the idea for a caravan (travel trailer) that would appear in different locations around Münster each week during the show. It has reappeared in every edition and has become a much-loved symbol of the project.

And this year in Münster, the process goes on. Together with his co-curators Britta Peters and Marianne Wagner, König has made sure that “the first artists we invited were young artists”. He reveals a certain toughness alongside his fabled sensitivity in making the artist selection. “Some of them are very smart, very activist-intelligent, but they think it’s an easy thing to be an artist, when it is the most fucking difficult thing to do,” he says. “So they had a high opinion of themselves and we said, ‘Come on, this is not a sculpture, this is not a physical necessity for 100 days.’” Some drop out at this stage. “We treat them extremely well. They come once or twice, and they make a proposal, and if it’s not feasible—either it’s too expensive or the effort is too enormous—then we say goodbye, and nobody is hurt.” Among those that made the cut this year is the Romanian artist Alexandra Pirici, born in 1982.

Many of the hallmarks that run through Obrist’s output began with König: he edited his first book with him—“my whole passion for editing books began with doing this book with Kasper”; his first museum show was a two-venue painting exhibition, The Broken Mirror, in Vienna, curated with König; he saw in König’s work the power of cross-generational exhibitions, of trusting and following artists rather than dictating to them; and he embraced his collaborative curatorial approach. Obrist says studying with König was “very organic … It was an amazing process to just learn on the job so quickly.”

He sees König as a teacher as much as a curator; it is this that has consistently provided König with a means to stay “connected to a younger generation of artists”, Obrist says. At the Städelschule, König notably married curating and teaching. “He accepted the invitation but only under the premise that he would also be given a space, the Portikus, where he could test exhibitions, and the school could be connected to an exhibition venue. It was very effective and practically very interesting, because you have both sides—you have the exhibition-making and the teaching of the next generation.”

Gonzalez-Foerster was present at one of König’s more difficult assignments, when he curated the edition of the travelling biennial Manifesta in St Petersburg in 2014. It “was not an easy context at all”, she says—events in Ukraine and growing concerns about artistic freedoms and human rights in Russia overshadowed the show. But there, too, she noted that “he is really into artists and at the same time has a vision of the total exhibition”.

She adds: “I really admire his practice as a curator and all his exhibitions, but also his way. He has a very artistic approach to curating, but not in the sense that he wants to be the artist. He’s just an fantastic curator.”'

The Snowman in the Volvo: König and Obrist’s first collaboration

Kasper König had come to know of Hans Ulrich Obrist through artists that the young Swiss curator and writer had befriended. Katharina Fritsch and Gerhard Richter recommended they meet, but the Swiss duo Peter Fischli and David Weiss prompted their first artistic collaboration.

“I did some errands for Fischli/Weiss at the time. From my late teens, I regularly visited them in the studio and they were my early mentors,” Obrist says. On their behalf, in 1990 he took a maquette for Snowman (1990)—“an eternal snowman, a snowman that never melts”, as he describes it—to Saarbrücken for a show curated by König at a nuclear power station. “My father had a very old Volvo and it never died, you could drive hundreds of thousands of kilometres in it. And so I would, with this old car, drive the snowman dummy to Saarbrücken and then hand it over to Kasper.”

• Artists’ Influencers, Hall 1, Friday 16 June, 10am-11.30am