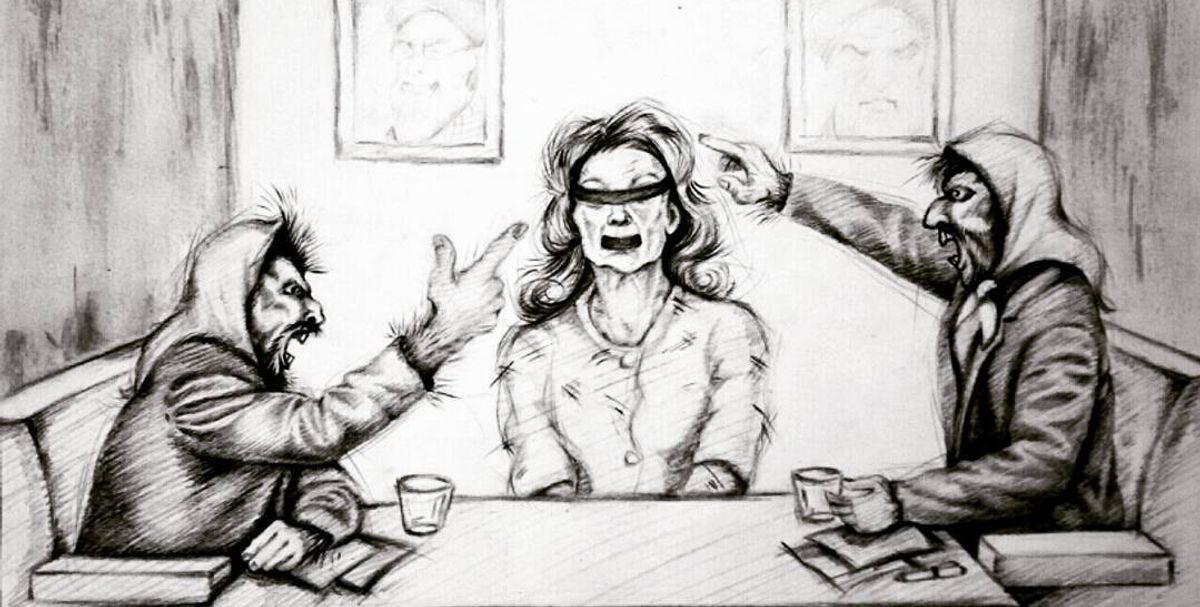

The Tehran-based artist Atena Farghadani, who was sentenced to 12 years and nine months in prison for her satirical cartoons depicting members of the Iranian government as monkeys and goats, says she is planning an exhibition of her protest art.

Speaking one year after her release from Evin prison, Farghadani says gallery owners in Tehran are too scared to mount such a show, but that she remains undeterred, posting critical works to Facebook and Instagram.

“I don’t intend to stop protesting or making political art,” Farghadani says in a podcast produced by Amnesty International. “My family is always checking up on me to see what drawings and cartoons I am producing. As I don't want to leave Iran, they get worried about me. But art is like a part of me and I can’t give up on political or protest art.”

In the podcast, Farghadani speaks out in greater detail than ever before about her harrowing ordeal in Evin and Gharchak prisons. She describes how she continued to create art by drawing on the paper cups used to distribute milk to prisoners.

“I’d gather flower petals and twigs in the prison yard and crush the petals into a paste to use as paint,” she says. “One of the drawings was of me at the moment of my arrest, sat in the car, about to be taken away. Some of the pictures were simply of my prison number: 93033. When one of the guards found my drawings in my prison cell, they stopped bringing me paper cups.”

One day Farghadani saw a paper cup in the toilet so she hid it under her clothes and went back to her cell. There she was attacked by two female guards. “They ripped my clothes off by force, tearing them,” she says. “One of them grabbed my arms and thrust me against a wall, pinning me there as the other woman searched me. I had lots of bruises and scars all over my chest and lower body where they had forced their hands into my underwear.”

The artist was first arrested in August 2014 for her cartoon that criticised two bills aiming to outlaw voluntary sterilisation and restrict access to contraception. She was sent to Evin Prison in Tehran and kept for 15 days in solitary confinement in a cell measuring 3ft wide and 5ft long. “It had no window and no toilet,” she says. “It was infested with insects and their stings irritated my skin. The cell was so dark that my eyesight deteriorated. It absolutely felt like I was in a grave.”

Farghadani was freed after two months, but rearrested after posting a video message on YouTube in which she says she was allegedly beaten by guards at Evin. She was sent to Gharchak Prison in the southern city of Varamin, and went on hunger strike over the appalling conditions there.

“[At Gharchak there were] 2,000 female prisoners, it was so overcrowded some had to sleep on the floor,” she says. “One section had four showers for 189 prisoners and only one hour of hot water per day.” Farghadani recounts incidents of rape and murder. “If anyone complained, they were threatened with solitary confinement. There was a prisoner in solitary everyone was afraid of, she had once raped a girl with a mop handle. No one ever complained.”

After 22 days on hunger strike, Farghadani was sent to Evin Prison where she remained in solitary confinement for three months before her trial. In June 2015, a Tehran court found the artist guilty of “spreading propaganda against the system”, “insulting members of the parliament through paintings” and “gathering and colluding against national security”.

She faced further allegations of “illegitimate sexual relations” with her lawyer who shook her hand after her trial. The pair was charged with “an illegitimate sexual relationship short of adultery” and indecent conduct, but was acquitted in October 2015.

Following an appeal, Farghadani's sentence was reduced to 18 months and she was eventually released on 3 May 2016. However, one year on and Farghadani says she suffers terribly from nightmares about being trapped in a toilet or confined spaces. “Much of what I have said today could get me in trouble, but I have decided to speak out because I have learned that when the media reports on an issue, others in the same situation won’t be treated as badly,” she says.

As for the future, she says she is sceptical about immediate change in Iran. “But I hope that future generations will see a democratic country, it’s hope for the future that keeps us going.”