In a defiant move in the face of Brexit, the Paris- and Salzburg-based art dealer Thaddaeus Ropac opened his first London gallery in Ely House, an imposing, five floor mansion in the heart of Mayfair today, 27 April.

“Brexit is the main topic of conversation, but the art world left behind its geopolitical borders a long time ago,” Ropac says. “We are part of an international movement, and so Brexit will not change anything.”

On a personal note, however, Ropac is less sanguine. “Morally, for me it was hard to swallow because I’m a staunch European,” he says. “One of the things that healed the tragedy of the Second World War and the Holocaust was this vision of Europe. That’s what I grew up with.”

His expansion in London is a boost for the UK art market, which has been buffeted by political and economic uncertainties after the UK’s vote to leave the European Union almost a year ago. “London will always be one of the quintessential art centres; it has the most successful museum in the Tate, a critical mass of galleries and an atmosphere of artists creating great art,” Ropac says.

Originally built in 1772 by Robert Taylor as the London residence of the Bishop of Ely, Ely House has been painstakingly restored by the art establishment's architect of choice, Annabelle Selldorf, who has designed galleries for David Zwirner and Hauser & Wirth as well as studios for Jeff Koons and David Salle.

Each of the distinct spaces on the ground and first floors, including a library and drawings room, have been transformed into four galleries. Offices and private viewing rooms occupy the upper floors.

The four debut shows, one in each gallery, are testament to Ropac’s international outlook (he represents around 60 major artists including European heavyweights Anselm Kiefer, Georg Baselitz, Imi Knoebel and the estates of Marcel Duchamp and Joseph Beuys). The exhibitions also reflect the gallery’s art historical range, from 20th-century titans to up-and-coming contemporary artists.

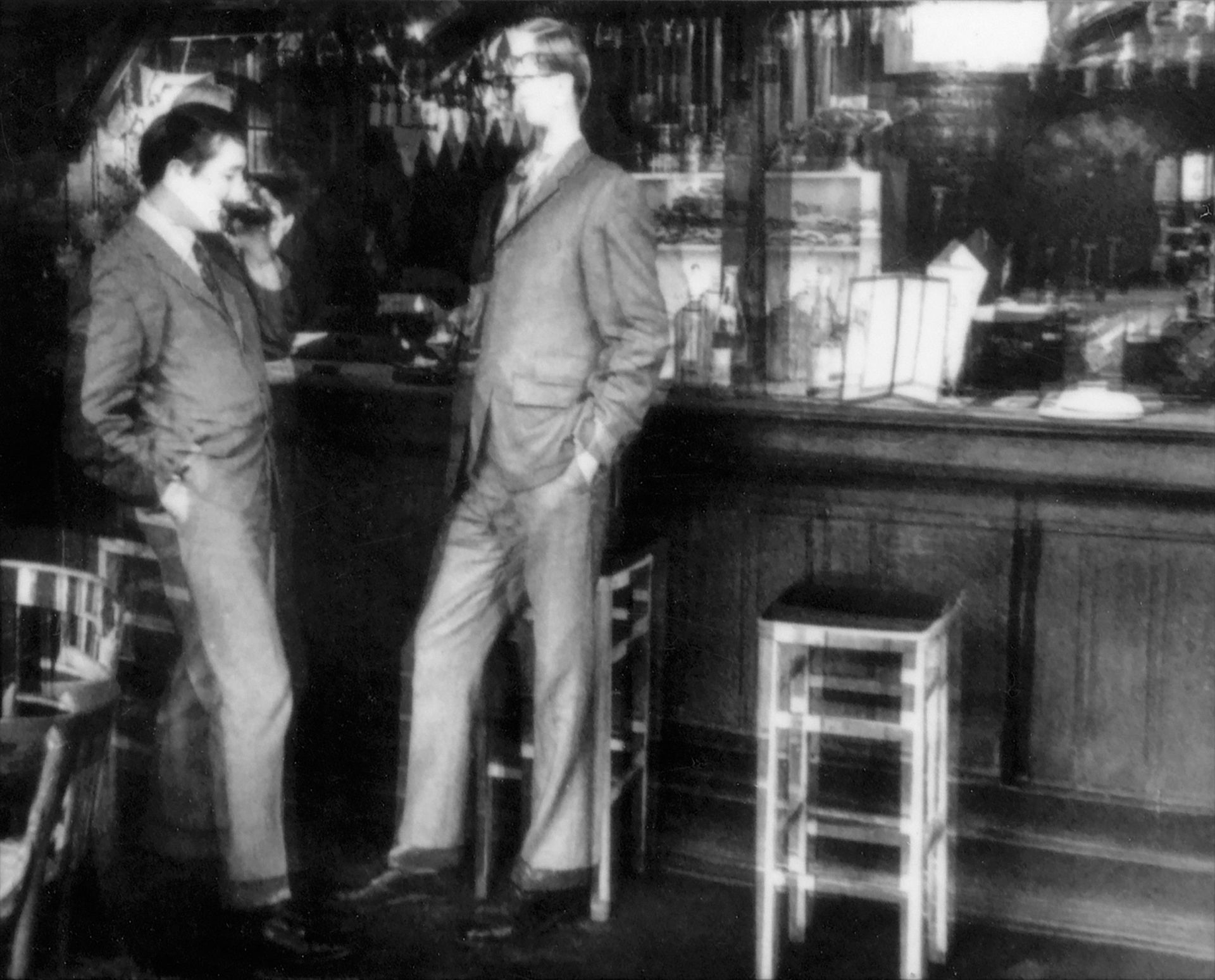

Twelve works from Gilbert & George’s Drinking series, dating from the early 1970s, have been installed among the 18th-century plasterwork adorning the walls in the Ely Gallery, formerly the Bishop’s sitting room. “Gilbert & George are part of my DNA,” Ropac says, noting that he has been working with the duo for 30 years.

Past the sweeping marble staircase, in the Berkeley Gallery, the young British artist Oliver Beer is showing Devils, a live sound installation broadcast through antique and modern vessels. Meanwhile, in the large hall at the foot of the stairs, five singers have been invited by Beer to respond to the natural frequencies, or voice, of the building. Titled Composition For London, the 15-minute piece will be performed every day for the next two months. “What better way to open a building than to find its sound,” Ropac says.

Upstairs, the bijoux Chapel gallery features a key sculpture by Joseph Beuys, Backrest of a fine-limbed person (hare-type) of the 20th Century AD (1972-82), plus drawings from the 1950s. Around a third of the drawings are for sale, priced between £25,000 and £300,000.

“Beuys is such a large part of my life,” says Ropac, who interned in the German artist’s studio in 1982 and has been working closely with Beuys’s estate since 2010. “He’s also such a part of London, with the Tate being very active and so on. But since Anthony d’Offay closed around 20 years ago, no gallery here has taken on Beuys.”

The final exhibition is dedicated to American Minimalists such as Dan Flavin, Richard Serra and Carl Andre. Ropac bought the 11 pieces from the Marzona Collection, a coup given that “everything else was gifted to museums”, he says.

Headed up by Polly Robinson Gaer, previously a senior director at Pace, Ropac’s London gallery joins a fleet of four extensive spaces in Paris and Salzburg, which is enough for now, the dealer says. Nonetheless he is eyeing up opportunities in Asia with the recent appointment of Nick Buckley Wood as his director in the region, plus an office in Hong Kong that is due to open soon.

“Our structure is very much tied to Europe, and I still see London as part of that,” he says. “But the art world is moving East and we are watching.”