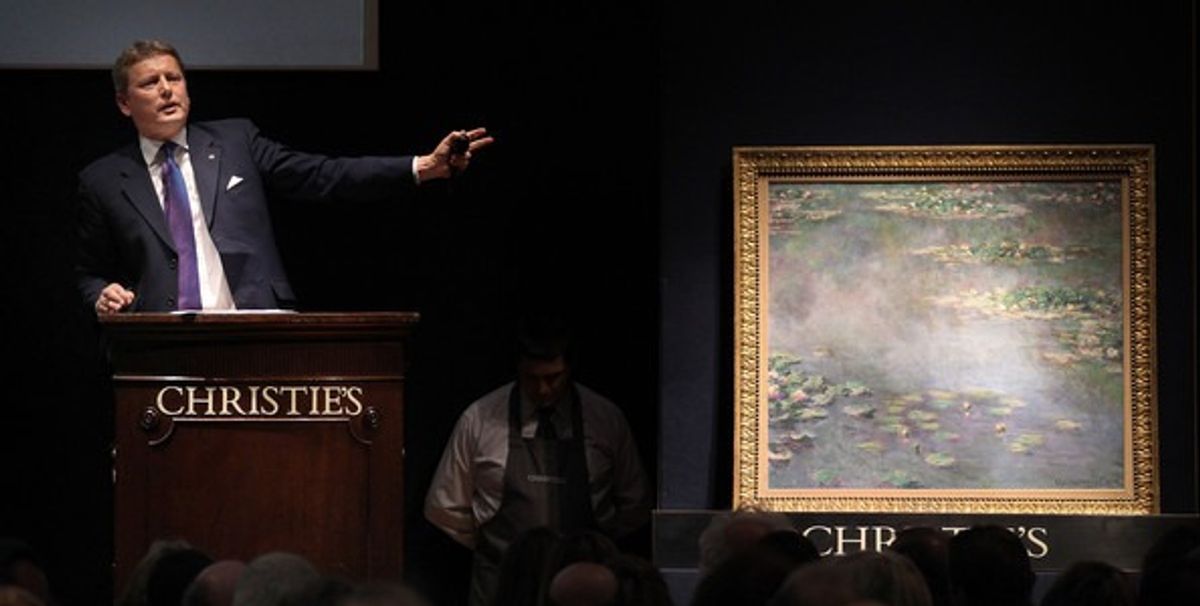

“Imagine having your pocket picked by a tongue,” says Nick Finch, Christie’s director of bids who is leading a training session in the arts of auctioneering. “That’s how one collector described being cajoled into bidding.”

Several other auctioneering metaphors crop up during the afternoon at King Street. Among them “game show host” and “circus ringmaster”. Charisma, salesmanship, humour and humanity are some of the other qualities Finch says Christie’s looks for in a potential auctioneer.

And of course there’s the numerical dexterity needed to keep track of the increments. Auctioneers usually take bids in 10% increments, but can be more flexible the higher the price climbs. “In the millions, any bid is a lot of money,” Finch reminds us.

But the ability to speak confidently in public must be the first requirement for any auctioneer. Finch recounts how Christopher Burge, “the best auctioneer of the past 50 years”, would calm his nerves before a big sale by “chilling in the department in his jeans and t-shirt”.

On occasion, a former actor whom Finch declines to identify is brought in to help budding auctioneers with their delivery. Reciting Humpty Dumpty while sticking your tongue out is a good lip-loosener, apparently.

Gavel in hand, trainees take our turns up on the Chippendale-designed rostrum. The original was destroyed when a bomb was dropped on King Street in 1941; no one was hurt and it is rumoured that Christie’s and Sotheby’s shared a space for a short while.

The first thing that hits you as you survey the saleroom is the number of channels you need to keep your eye on. There are bids in the room, which you need to elicit with a smile, then there are the “absentee” bidders listed on your sales sheet. We are reminded on more than one occasion not to forget to bid on their behalf and to try and engineer proceedings so that the maximum bid rests with them, where possible.

And then there’s the online bidding, which is becoming an increasingly popular channel for Christie’s, with a third of people registering for live sales last year doing so online. A training line set up to look as if someone is bidding online in Tampa, Florida occasionally flashes up.

Add to that reserve prices (the lowest amount a lot can be sold for, as agreed with the seller) and consecutive bidding (a legal practice whereby an auctioneer acknowledges a phantom bid as long as it’s below the reserve price). It’s a headache-inducing mix.

The auction business has dramatically changed since 5 December 1766, when James Christie sold his first lot at 83-84 Pall Mall–a set of six breakfast pint basins and plates, which went for 19 shillings.

Without any marketing material to whet a buyer’s appetite before the sale, for every lot Christie would read out a long description, sometimes lasting ten minutes. He averaged 100 lots in one day; now the auction house whips through 60 to 80 lots every hour. “Christie’s sales were great social events, they were more popular than the opera at nearby Covent Garden,” Finch says.

Evening sales are still celebrated social events, where many of the art world’s biggest players come to hob nob. “But most bidding is now done online or via the telephones,” Finch says. “Nonetheless there is still a great need for auctioneers; the show must go on.”

More and more women are also being encouraged to take up the profession. Out of 61 auctioneers employed globally by Christie’s, 20 are women. “We have certainly evolved as a company,” Finch says. “Public school boys used to be the face of Christie’s, but our image has changed very much over 250 years.”