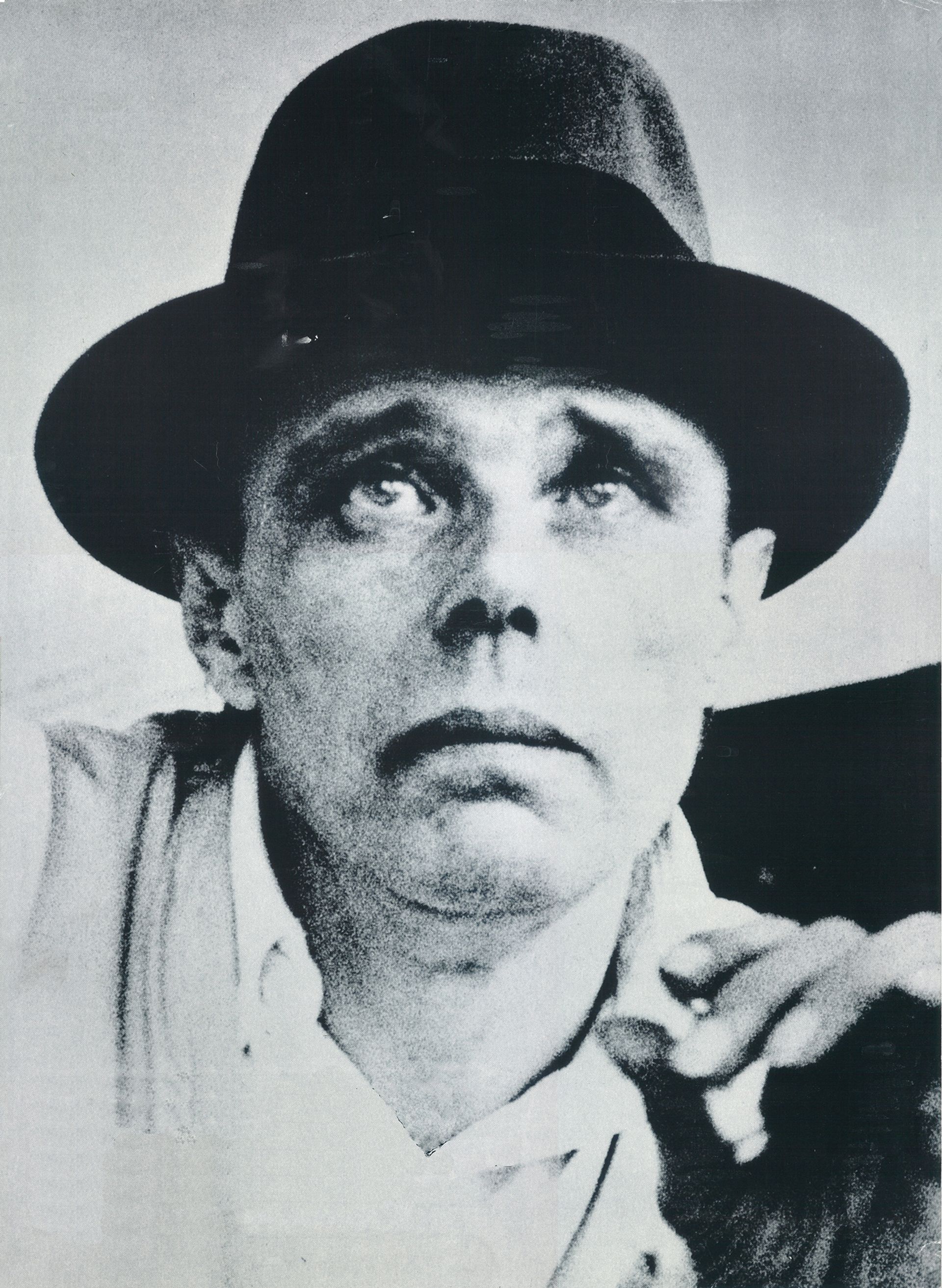

The Austrian dealer Thaddaeus Ropac is due to open his London gallery at Ely House in Mayfair on 28 April with four shows—one of them dedicated to Joseph Beuys (1921-86). But a year from now, Beuys will have the run of the place, with all four exhibition spaces in the Georgian townhouse devoted to the German conceptual artist. It will be the biggest commercial gallery show for the artist in London in two decades.

Ropac, who has galleries in Salzburg and Paris, is betting that the market for Beuys has room to grow. The dealer first encountered the artist during an internship in his studio in 1982 and has been working closely with Beuys’s estate since 2010. Although supported by institutions, the famously inscrutable artist has had an uneven track record when it comes to sales. Perhaps surprisingly for an artist of Beuys’s stature, his auction record is below £1m, but Ropac says his primary market prices are “much higher”.

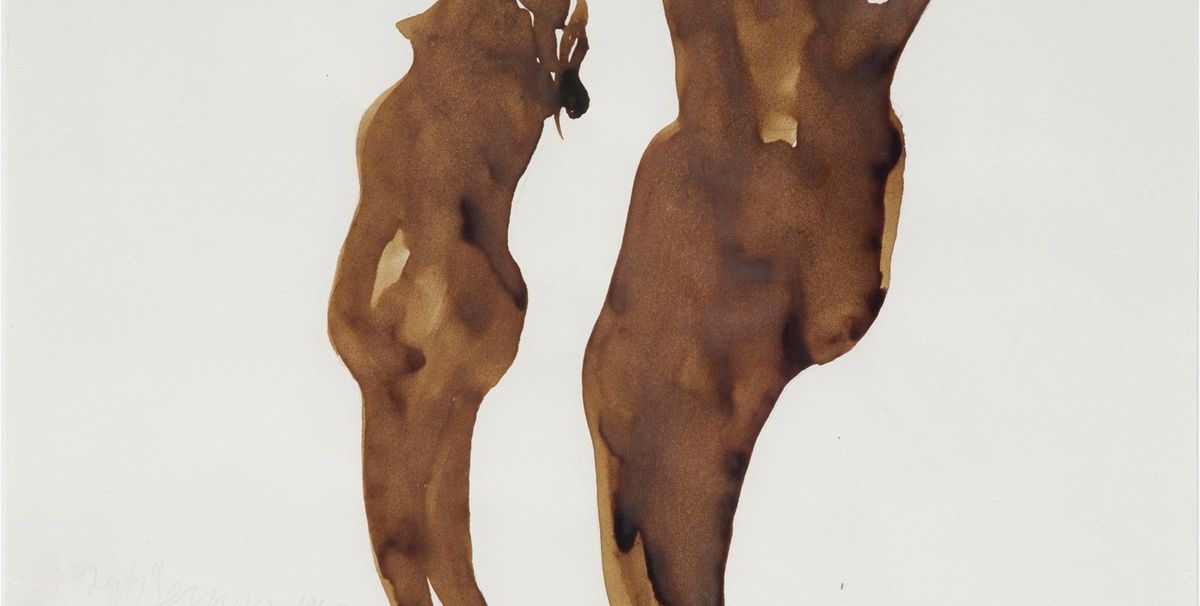

The key piece in Ropac’s presentation this month is also expected to surpass Beuys’s top price at auction. Backrest of a fine-limbed person (hare-type) of the 20th Century AD (1972-82), an iron multiple that Beuys cast from a therapeutic backrest used to treat young children, is priced at €2.5m. Created in an edition of 12, another backrest sold at auction ten years ago for £254,400. Ropac’s version, an artist’s proof that Beuys placed in a vitrine in 1982, will be installed in the first-floor Chapel Gallery with around 40 drawings from the 1950s, a third of which are for sale, priced between £25,000 and £300,000.

Addressing the issue of valuation, Ropac says: “Certain artists are difficult to sell at auction. Beuys’s work can be complex to install.” If this has kept major pieces from coming up for auction, important works have nonetheless been changing hands privately. Of a list of works he compiled in 2005, only 20% are still in the same collection, Ropac says.

Henry Allsopp, the worldwide head of Latin American art at Phillips, agrees that Beuys does not have the same immediate aesthetic appeal as Sigmar Polke or Gerhard Richter. “The conceptual nature of Beuys’s work somewhat undermines the market. He was trying to democratise art,” Allsopp says. “He also created editions, which doesn’t really lend itself to building a market.”

Nonetheless, Phillips London sold a felt suit, created in an edition of 100, for £81,250 in January, over its high estimate of £70,000. The result represents a small growth spurt in prices; in 2012 Phillips in New York sold one for £59,000. Before that, Beuys’s felt suits went in and out of fashion at auction; one sold in 1989 for £50,000 and another in 1999 for £13,000.

Momentum is building internationally as well. Allsopp says an exhibition last year at Bergamin & Gomide gallery in São Paulo was well received. “There are obvious parallels between Beuys and Neo-Concrete art,” he says.

But it is London that will host the great German conceptualist this spring. “London has always understood Beuys,” Ropac says, pointing to Anthony d’Offay’s landmark Beuys show in his Dering Street gallery in 1980, and acquisitions by the Tate. “We feel there is a need for Beuys in London, so we are stepping in.”