Every year, millions of commuters pass through an all-encompassing art installation of vibrantly coloured mosaics in London’s Tottenham Court Road underground station. While many may not realise it, this vast collage, drawn from images related to technology, jazz music, ethnography and Modern life was designed by Eduardo Paolozzi (1924-2005), one of the so-called “godfathers of Pop Art”.

His style may seem familiar now, but it has been hidden in plain sight and the current survey at the Whitechapel Art Gallery is the first major show of his work in a London institution since 1971, although Paolozzi has recently been the subject of substantial exhibitions outside the capital at the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester in 2013 (which I organised) and the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in 1999.

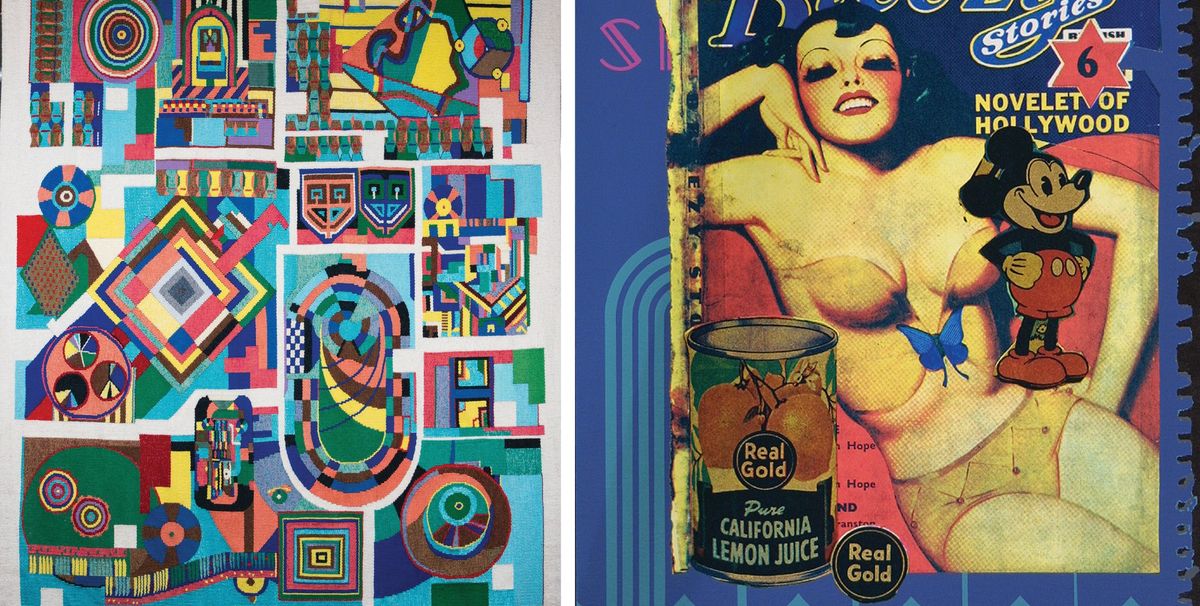

Daniel Hermann, the former curator of the Scottish institution’s Paolozzi collection, is responsible for the Whitechapel exhibition and he brings to it a light touch. Although there is a substantial catalogue with contributions from writers including Hal Foster, Jon Wood and Beth Williamson, there is very little interpretation in the exhibition. Instead the argument is largely visual: a dialogue between an astonishing array of media ranging from robotic figures to tapestries, ceramics, a film and even a Lanvin-brand blouse and skirt.

Although it spans 50 years, from the 1940s onwards, Paolozzi’s prolific output is presented in a way that emphasises his relevance to contemporary art, repositioning him for an audience used to experiencing art in a constantly changing digital landscape. On entering the exhibition, the visitor is immediately faced with a recreation of his event at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts from April 1952: projected images taken from post-war American advertising, science fiction and popular magazines. The combinations are subversive and witty, and act as a bridge between European Surrealism and the aesthetics of consumer persuasion that was to define American Pop Art in the subsequent decades.

Paolozzi once claimed that “all human experience is one big collage”—a statement that reflected his experience as the son of Italian immigrants growing up in the working class Scottish port of Leith. Born in 1924, his adult interest in consumer culture was shaped by his experience helping in his parents’ ice cream and confectionery shop after school. It also resulted from collecting cigarette cards of film stars, aeroplanes, battleships and motorcars. Although he is considered one of the most important post-war sculptors—and a key figure in the “Geometry of Fear” group of artists, who worked with an “iconography of despair,” according to the critic Herbert Read—it is collage that underpins all Paolozzi’s work, regardless of medium.

Powerful influences

This is strongly conveyed in works from the late 1940s and 1950s, when the artist was working in London after studying at the Ruskin and Slade Schools. The non-Western art he saw at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford and in French ethnographic museums during a spell in Paris from 1947-49 (during which he befriended arists such as Alberto Giacometti and Tristan Tzara) had a powerful influence. Collages, drawings and totemic sculptures of organic and mask-like forms made after his sojourn reflect his time in France.

In the show, sculpture, printmaking and collage are presented as a continuum, underlining the diversity and inter-relatedness of Paolozzi’s work. He abandoned the traditional hierarchies between different media when he founded the textiles, wallpaper and homeware company Hammer Prints with Nigel Henderson in 1954. Abstract patterns are displayed alongside screen prints that tap into ideas of the unconscious Paolozzi developed with the theorist Anton Ehrenzweig.

His central role in the Independent Group of artists, architects and theorists (which also included Rayner Banham, Richard Hamilton and the architects Colin St John Wilson and Alison and Peter Smithson) is emphasised through works like the Contemplative Object (around 1951), an organic sculptural form that was shown in the seminal exhibition This is Tomorrow at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1956. Paolozzi’s ability to tap into the existential anxieties of the Cold War comes through in sculptures like his Maquette for the Unknown Political Prisoner (1952), a fractured group of totemic figures. The pitted surfaces of Paolozzi’s isolated figures suggest survivors of a nuclear holocaust. The critic Lawrence Alloway observed that “the consuming interest of Paolozzi is the physiological and psychological limits of man”, which had “been widened lately, with concentration camps, exposure at sea, the pressure of -45 gravities.”

Paolozzi is often associated with machine aesthetics, but his relationship with it later became ambivalent. His J.G. Ballardian depictions of crash test dummies and a garish image of a smiling elephant painting an American flag were a rejection of uncritical images of automobiles, slick household goods and exotic foodstuffs. Sculptures like 100% F*rt (1971), which criticised the art world, inevitably undermined his later reception and relationship with art dealers. But he went on to develop an alphabet of shapes, often inspired by jazz music, that characterised his public sculpture of the 1970s and 1980s, through which he regained some stature. In these works and others, as Alloway wrote, Paolozzi’s work “integrates the modern flood of visual symbols, a primary fact of urban culture, with his art”.

• Simon Martin is the director of the Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

• Eduardo Paolozzi, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, until 14 May