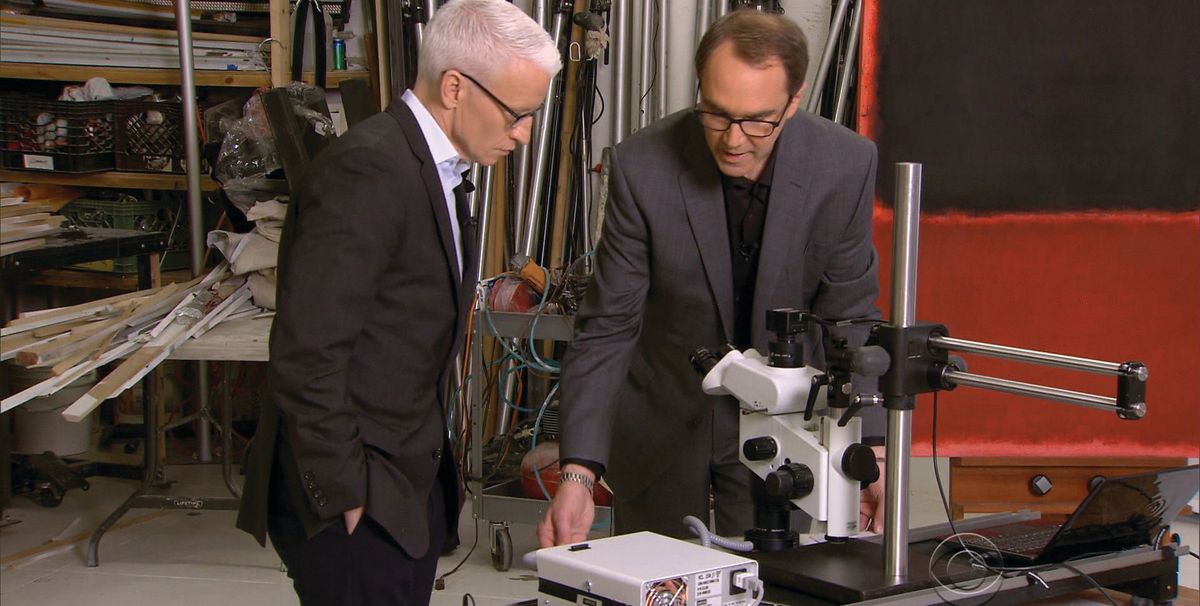

Forensic scientists usually stay behind the scenes, shining a strong light on fine art. Sotheby’s appointment of James Martin as its director of scientific research—and its acquisition of the firm he founded, Orion Analytical—has turned the spotlight on the experts.

Prior to the recent art market boom, scientific laboratories for art were mostly the preserve of institutions. But in recent years, small businesses focused on conservation have begun offering some types of analysis to private clients. There are now a handful of dedicated art labs, of which Orion was perhaps the best known.

The establishment of the first in-house scientific research department at a major auction house “is indicative of where the market is going”, says Colette Loll, the founder of the specialist firm Art Fraud Insights, based in Washington, DC. “It’s all about mitigating risk.”

Sotheby’s move has also effectively taken off the market a leading figure in a niche and fragmented field just as demand from buyers, and their lawyers, is growing. “There is a hole that hopefully someone will fill, but it takes entrepreneurial nerve to leave a museum job and do this… it’s not for the faint of heart,” says John Cahill, a lawyer who represented two plaintiffs in suits related to fakes sold by the Knoedler gallery.

The sector has considerable barriers to entry. Expensive equipment and lengthy training are only the start; analysts also need to be comfortable being the bearers of bad news, as most works are questioned for a reason. Their findings can be dragged into lawsuits. Martin’s testimony last year that a consultant for Knoedler had asked him to alter a report regarding works purportedly by Robert Motherwell was a turning point in the ultimately settled case brought against Knoedler by Sotheby’s chairman Domenico De Sole.

For Sotheby’s, which under chief executive Tad Smith has spent much of the past 12 months adding in-house expertise to its core auction business, Martin’s hire adds distinction. The new department will primarily support the auction house’s specialists and researchers rather than its clients directly.

If Martin can weed out even a few major fakes before they arrive on the auction block, the firm’s investment will probably prove cost-effective. Last October, Sotheby’s reimbursed the buyer of an £8.4m painting purportedly by Frans Hals after Martin identified modern materials in the work. The seller says that more forensic analysis needs to be done before making a final judgment.

In January, the auction house confirmed that it was reimbursing a client $842,500 for a work it sold in 2012 as from the circle of the 16th-century artist Parmigianino but which was found to be “undoubtedly a forgery”, according to a Sotheby’s statement. The auction house submitted both works to Martin when he was at Orion.

Forensic proof? The value of forensic analysis is expected to grow as authentication boards shut down, art historians become reluctant to offer opinions, and technology improves. “Forensic analysis can see more deeply and more subtly into works than it could even ten or 15 years ago,” says Jack Flam, the president of the Dedalus Foundation, which gives opinions on the authenticity of works by its founder, Robert Motherwell, and which used forensics to identify Knoedler fakes. He calls Sotheby’s acquisition of Orion “rather brilliant”.

In a field riddled with disputes, one more expert view—particularly with the comfort of science behind it—can make a huge difference. “When you have someone who can speak to methods that are generally reliable and thus admissible in federal court, it’s tough to beat,” says Jordan Arnold, the senior managing director of K2 Intelligence, who oversaw several art fraud cases when he was an assistant district attorney in Manhattan.

Nevertheless, some think the emphasis on technology is overkill. “Science is never black and white,” says Stuart Lochhead, the managing director at Daniel Katz Gallery. “You are relying on the calibration of a machine, how samples are taken. There’s a bit of a concern that everything will now have to be tested.” Still, he acknowledges the value of certain analyses, citing thermoluminescence testing, which can determine in what century an object was made.

Even the scientists admit their methods are not fail-safe. “Just like in any other industry, I’ve seen bad reports and junk science,” Loll says. Some regard seemingly objective methods, like the identification of an artist’s fingerprints in a work, as too easy to manipulate. Forgers can also go to great lengths to use historically accurate materials. Martin describes forensic analysis as a “powerful tool to understand art, especially when used to support scholarly connoisseurship and historical research, as part of a tripartite model”.

While forensic analysis is often used when there is a major question about an expensive work, such as a provenance gap, collectors are increasingly using it to understand better how to care for their holdings. Vittorio Calabrese, the director of the Olnick Spanu collection of post-war Italian art, has been working with a laboratory in Rome. “Scientific analysis is quite important to assess the stability of the various unusual or unconventional materials,” he says.

Buyers’ reluctance Not every collector will request pigment analysis before handing over their credit card, though. “Buyers are still reluctant to do a lot of pre-purchase research,” Cahill says, adding that even on transactions over $100m, deeper analysis is not always taken up. Some collectors do not want to offend the dealer or appear “uncool”, as Cahill puts it, while others bristle at the additional expense. Tests start under $1,000, but more molecular investigations, such as pigment analyses, can cost tens of thousands of dollars. Although the legal obligation to ensure a work’s authenticity usually falls on the seller, Cahill says it can be “wise” for a buyer to take such measures. Nicholas Eastaugh, director of London-based Art Analysis & Research, says forensic analysis should be standard when purchasing art “in the same way as when you buy a house, you get a survey done”.

High-tech future Rapid developments in technology could make authentication debates a thing of the past. New options include a tamper-proof label or embedded tag encoded with a digital record. Lawrence Shindell, the chairman of Aris Title Insurance, which sponsors the non-profit i2M Center, likens i2M labels to vehicle identification numbers in the car industry. By scanning a label on a work with an app, individuals can confirm its authenticity, add to its provenance and even record details of its conservation. Tagsmart, meanwhile, offers synthetic DNA tags for artists to apply before a work leaves the studio (Marc Quinn and Idris Khan are among the early adopters).

Steve Cooke, the chief product officer at Tagsmart, praises the “growing understanding of what is happening in materials at a molecular, or even a quantum, level”, but warns: “You can present artists with really cogent, scientific reasons [to incorporate tags] but you often get pushback.” The scientists still have their work cut out.

The analysts’ case-cracking tech

Visual and magnified inspection

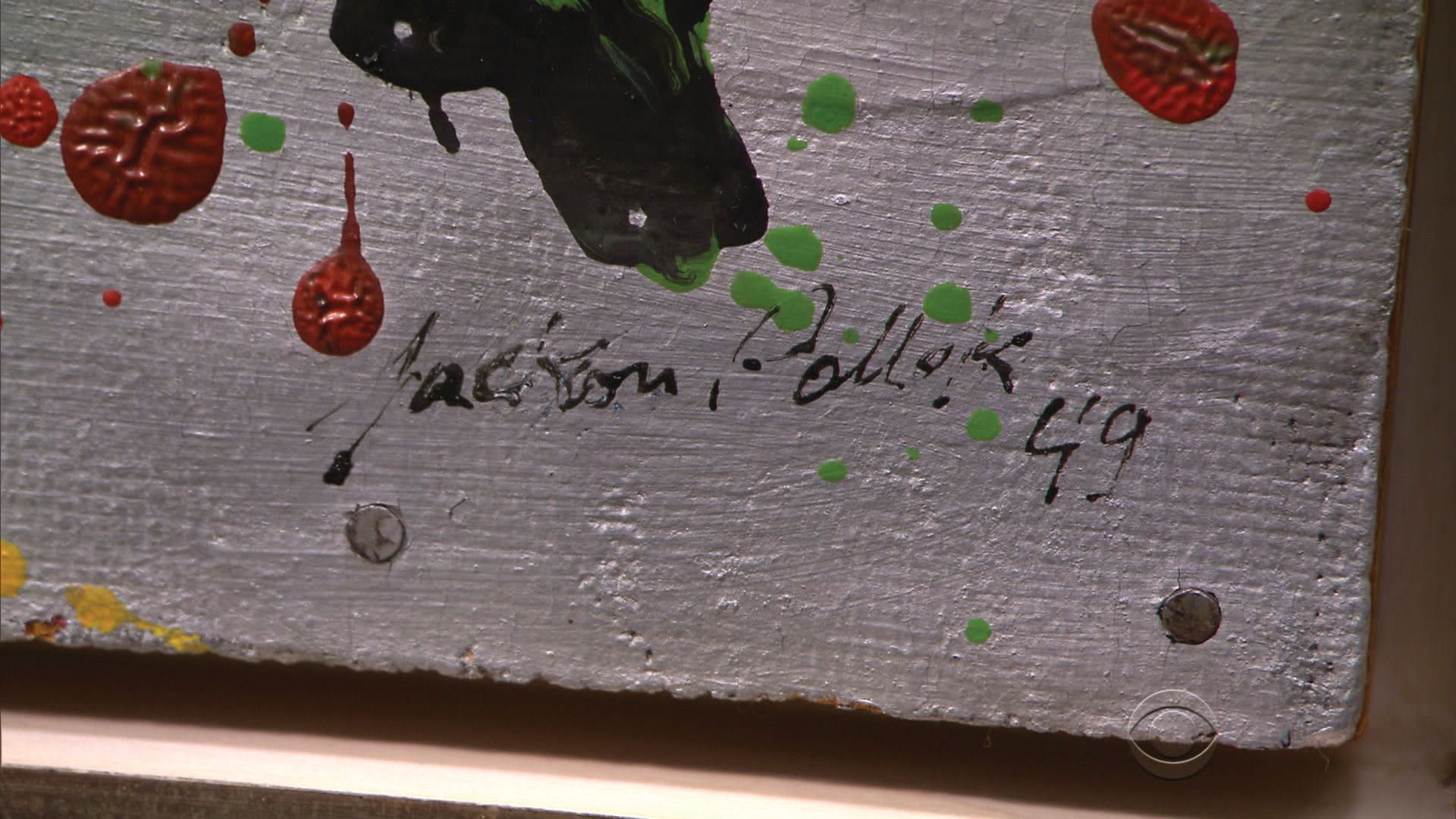

Discrepancies can often be found simply by looking closer. Magnification of up to 90 times is possible under different kinds of light, allowing investigators to discern whether cracks in a painting are real or simulated, or if a signature has been applied over damage or restoration. James Martin of Sotheby’s says that one work he examined as part of the recent Knoedler investigation was signed “Jackson Pollock”, but “close examination with a stereo microscope revealed that the signature was painted over a precise tracing of a genuine signature”. Subsequent molecular analysis of the paints revealed materials that had not been developed until decades after the artist’s death in 1956. Another purported Pollock had a misspelled signature.

The artist is a forgers’ favourite in part because records of his output are rather haphazard. Many mistakenly believe that his drips and pours are easy to replicate.

Elemental analysis

This technique identifies the quantities of elements such as lead or zinc that are present in paint and other cultural property. The underlying science has been around for decades: in 1954, an x-ray radiograph on a painting attributed to Francisco Goya (Portrait of a Woman) suggested the presence of zinc white, a pigment that was rarely used in the artist’s era.

Nowadays the process is most commonly undertaken by a portable x-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer, and is often used by galleries or art fairs to help vet works. XRF can find historically inaccurate elements, such as cadmium and selenium in red paint, which would date a painting to after the 19th century.

Prices of handheld XRF devices are coming down—a rarity in an otherwise expensive field—but the technology has its limits. As Martin points out: “Groups of elements can make different compounds, like different letters can be arranged to make different words.” Just as problematically, different elements can display similar features: barium, for instance, can mask titanium, an element whose presence would push a painting’s date into the 20th century.

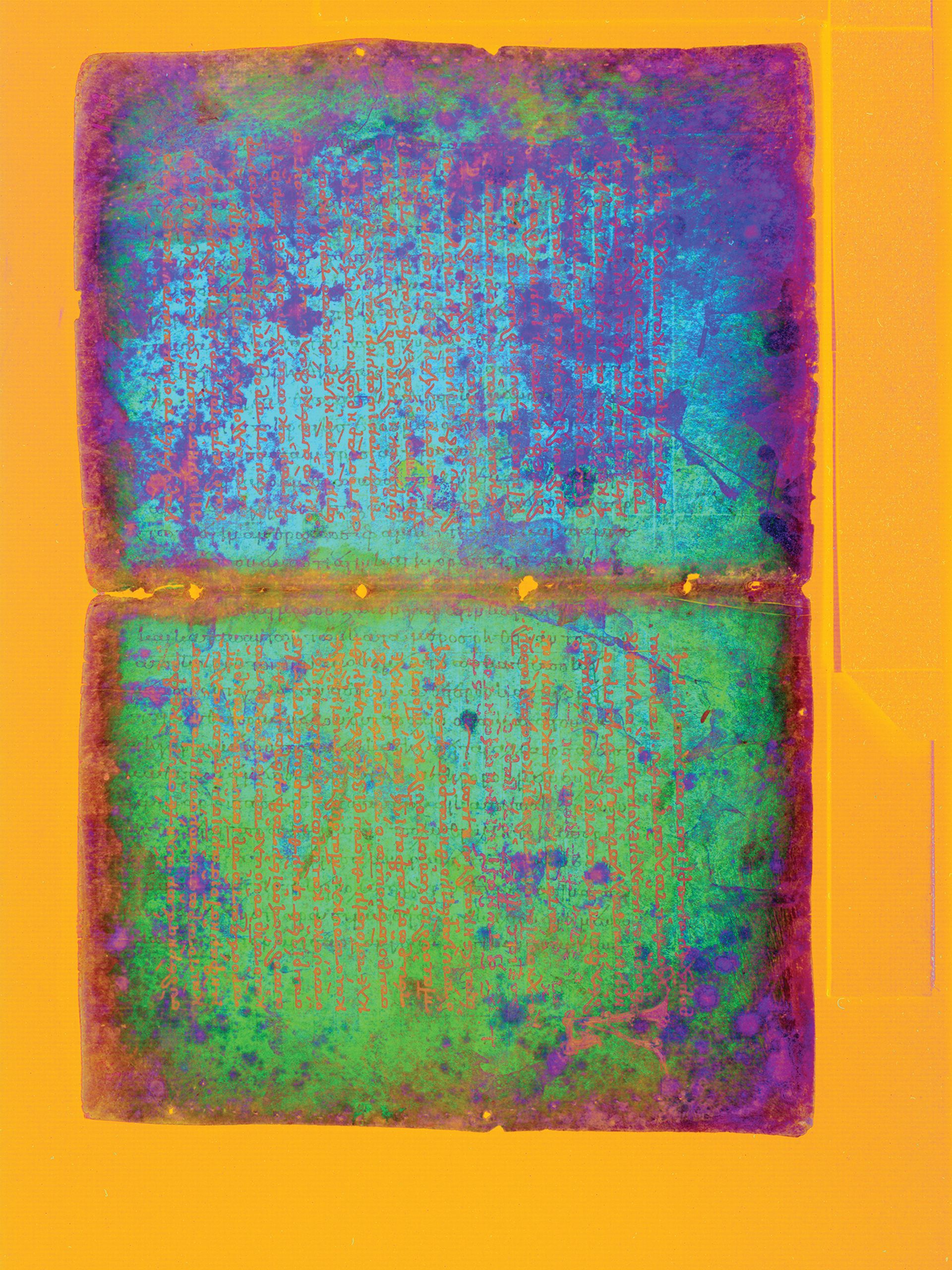

Molecular analysis

One of the downsides of publishing technical studies is that would-be forgers can use the information when making fakes. The German forger Wolfgang Beltracchi, who was convicted in 2011, was careful to use paints that listed ingredients he knew were historically accurate. But he was unaware that some paint manufacturers use synthetic organic pigments to boost the colour of inferior paints, and these traces were detectable through molecular analysis. Using Raman spectroscopy—which detects molecular vibrations with laser beams—Martin found phthalocyanine green, a pigment first introduced in the late 1930s, in a painting that was dated in the 1920s.

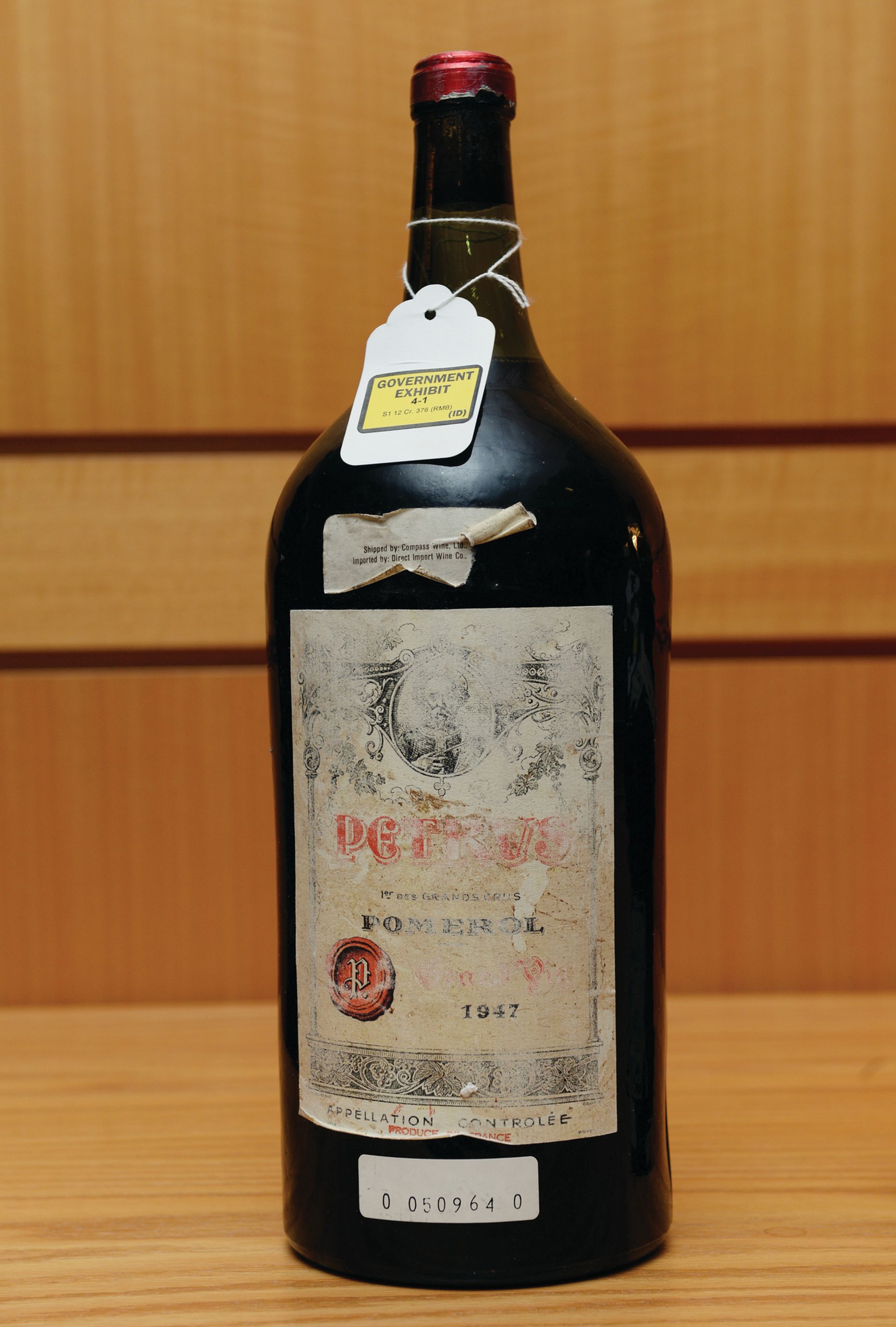

Old-fashioned detective work

“A big part of what I do is good old-fashioned research,” says Martin. In 2012, he examined evidence for the US attorney and the FBI in the Rudy Kurniawan wine fraud case. Kurniawan, a dealer in fine wines and a frequent consignor to wine auctions, was sentenced to ten years in prison in 2014 following his conviction for wine fraud.

Martin noticed that many of the paper wine labels found in Kurniawan’s apartment featured the same watermark, and he used the internet to track down the Indonesian manufacturer, which confirmed that it had only started producing the paper in the 1980s.

Martin’s evidence was not needed at trial, however. When FBI agents raided Kurniawan’s home, they found a fully equipped wine laboratory.