On the heels of a US election season riddled with cries of “fake” and “rigged”, it is worth remembering that certain Modern artists embraced those exact qualities as being more truthful than truth itself. None did this more so than Francis Picabia (1879-1953).

From the outset, he was blatantly fraudulent. Reeking of unabashed insincerity, he cannibalised every -ism he encountered, chewed it up and joyfully spit it back into the faces of the establishment. David Bowie used to say that he wasn’t really a rock star, but an actor playing a rock star. The same could be said for Picabia: he played the role of an artist, producing an oeuvre of spectacular fakeness—fake Cubism, fake Surrealism, fake Social Realism, fake Romanticism, and finally, in his last works, fake Dadaism. For a half century, Picabia brilliantly trolled the art world. Everything he did was purposefully “wrong.”

Nowhere is this more apparent than in his first body of “mature” work, a series of “bad” Impressionist-style paintings that he made in his mid 20s. Looking at them in his career survey at the Museum of Modern Art, you sense that something is very off. Instead of the lyrical play of light and air that are the hallmarks of Impressionism, these are wooden, static and claustrophobic. Desperate for some explanation, I turned to the wall text: “Picabia is believed to have worked from photographic postcards rather than immersing himself in nature and painting outdoors. In this he travestied the original spirit of Impressionism and that style’s en plein air (in the open air) techniques.”

The master of kitsch

It’s hysterical—he cheated! And what’s more, when these paintings were shown, they were lauded. One reviewer enthusiastically declared: “Never would we have dared imagine that M. Picabia could arrive so quickly at this maturity, this mastery.” It was a great prank, but it was more than a mere leg-pull; it was an act of institutional critique perpetuated on Impressionism before the paint on their pictures had dried (Picabia’s works were painted in the early 1900s). Picabia outed Impressionism’s secret relationship to technology; after all, as photographs of Monet in his studio prove, he did not always paint en plein air. And wasn’t his serial way of working influenced, in part, by photography? In retrospect, Picabia’s faked Impressionism is every bit as authentic as Monet’s.

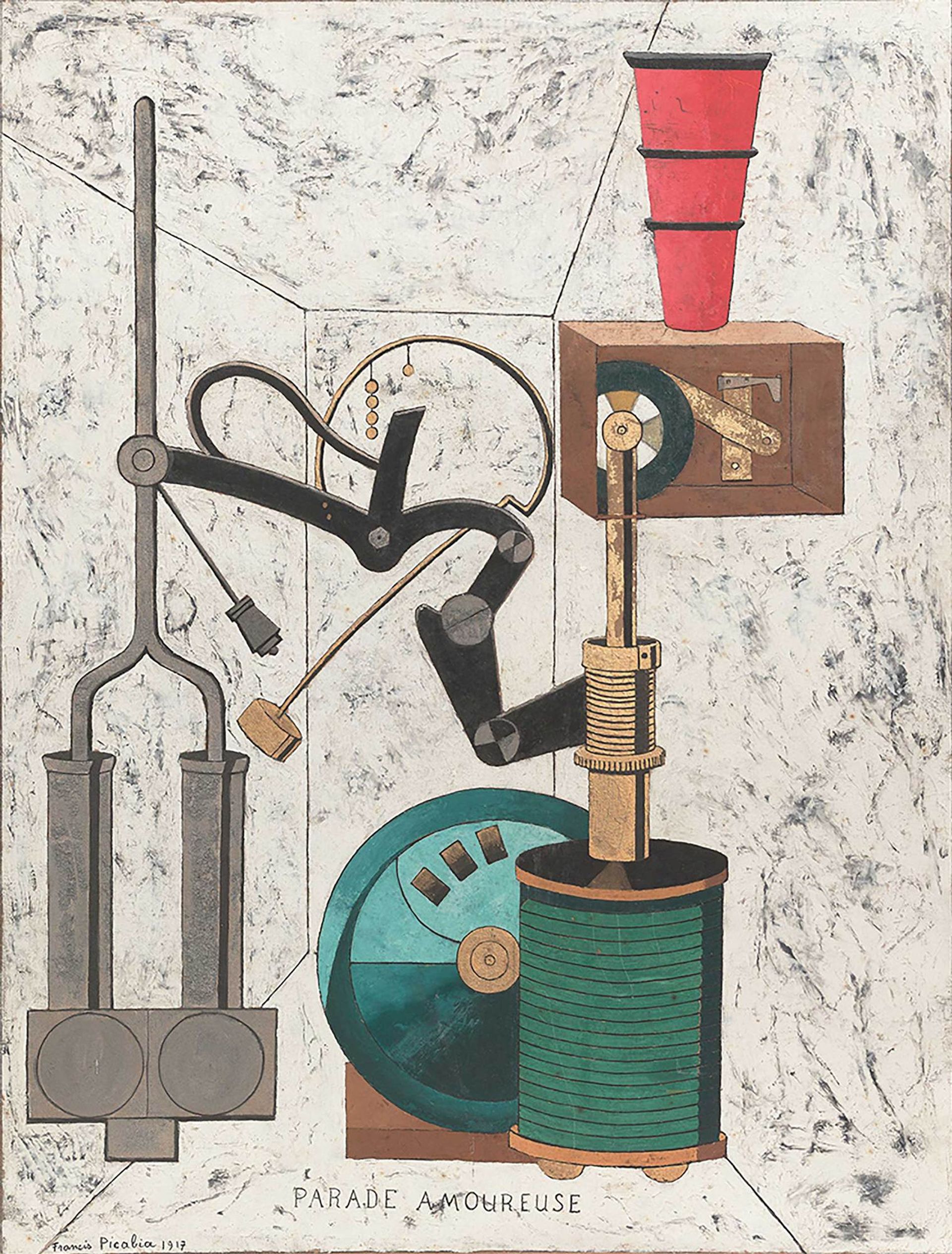

His take on Cubism was equally skewed. As opposed to Picasso or Braque’s finely crafted, small-scaled, monochrome, brainy canvases, he produced eight-foot tall Expressionist abstractions drenched in brash color. Instead of café culture tropes—chair caning, absinthe bottles and newspapers—Picabia’s Cubist paintings depict what looks like the motion of fleshy bodies having sex seen from many angles. In the mid-1920s, after Cubism blew over and things swung back toward figuration, Picabia followed suit by using kitschy postcards as the basis for his “Romantic” figurative work. By the early 1940s, during the French Vichy regime—and shortly before his arrest as a Nazi collaborator (the charges were later dropped)—he made “bad” Social Realist paintings derived from images he swiped from softcore porn magazines. Although they came awfully close to the style of Nazi-sanctioned artists, there was something “wrong” about them; they were too perversely weird to ever pass for official art. And so it goes until the early 1950s when he deconstructed Dada—his own movement, if he ever had one—with a series of painterly dots that referred back to his mechanical works of the 1910s. Bereft of any political or artistic urgency, he purposely deflated his own radical legacy into decorative pabulum.

Ironically, the only gallery that rings of true authenticity is the one dedicated to his earlier Dada period from 1915-22. The heroic mechanical paintings and drawings based on machines and industrial parts are entirely original. The same goes for his profusion of ephemeral journals, poems and prints, which are typographical masterpieces of invention, beauty and elegance. Yet weirdly, his Dada room contains the least amount of Dada sprit in the entire exhibition.

What Picabia predicted

There is no one iconic image that stands for Picabia in the way that, say, water lilies do for Monet or soup cans do for Warhol. By comparison, Picabia’s oeuvre is an ongoing series of purposely “weak” images that dance around Modernism’s strong points in order to undermine them. But from a 21st-century digital perspective, the “poor” image—as critics like Hito Steyerl and Boris Groys have suggested—is an effective way of critiquing power structures. Picabia, it seems, predicted the way images would be circulated and consumed in the digital age.

The timing of the show is perfect: in Dada’s centenary year, America elected a latter-day Ubu Roi for president. The Dada dictator first imagined by Alfred Jarry in his 1896 play of the same name is a narcissistic kleptocrat who impetuously invades various countries, swears like a sailor and sets about robbing his populace blind. He specialises in disinformation and is the early Modernist embodiment of “post-truth”. You can almost hear Picabia on the sidelines giggling with delight, saying: “See? I told you so.”

• Kenneth Goldsmith is a poet and the author of Wasting Time on the Internet (Harper Perennial) and Capital (Verso)

• Francis Picabia: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction, Museum of Modern Art, New York, co-organised by the Kunsthaus Zurich, until 19 March