It was number 493 of the 681 submissions to a 1971 architectural competition set up by the French government for a grand cultural centre on the Plateau Beaubourg in Paris. The design by the young architects Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers (together, less famously, with Gianfranco Franchini and the engineers Ove Arup), was a radical proposal for “the construction of a building for information, fun and culture, a sort of machine, an ‘informative tool’”, as Piano and Rogers put it.

With glass walls and an outer skeleton in elegant cast steel, in which the usually hidden or underplayed functions of buildings—staircases, escalators, ducting, cooling towers—were unabashedly exposed and foregrounded, it prompted shockwaves in the French capital (and beyond). “It’s an extraordinary tribute to the jury to have recognised these two great architects so early on, and not have gone for a more renowned practice,” says Hans Ulrich Obrist, the artistic director at the Serpentine Galleries. “And it’s probably the best jury for any building in the 20th century: it included Jean Prouvé, Oscar Niemeyer and Philip Johnson.”

It took another five and a half years, and various modifications, for the 700m franc, 100,000 sq. m building to be completed. But it instantly welcomed a broad and curious public. Inside and around the Beaubourg complex were the Musée National d’Art Moderne; the Centre de Création Industrielle, dedicated to industrial design; a huge, free public reference library; and the Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique (Ircam), which took a scientific approach to music.

The programme seized on the building’s radical spirit. Led initially by the Swedish director Pontus Hultén (“a genius”, says the artist Philippe Parreno), it was from the start interdisciplinary. It opened with shows dedicated to Gerhard Richter and Marcel Duchamp (“This exhibition pays tribute and gives justice to an artist whose work, regarded as major outside France and at the origins of contemporary art, has remained singularly misunderstood and even ignored in his own country,” the press release said of the Duchamp show). Pioneering group shows followed, in particular four seminal surveys of international avant-gardes: Paris-New York (1977), Paris-Berlin (1978), Paris-Moscow (1979) and Paris-Paris (1981).

To mark the 40th anniversary of the Pompidou, also known as Beaubourg, we asked leading cultural figures to ponder its legacies, artistic and architectural, and to highlight moments in its history of particular cultural or personal significance.

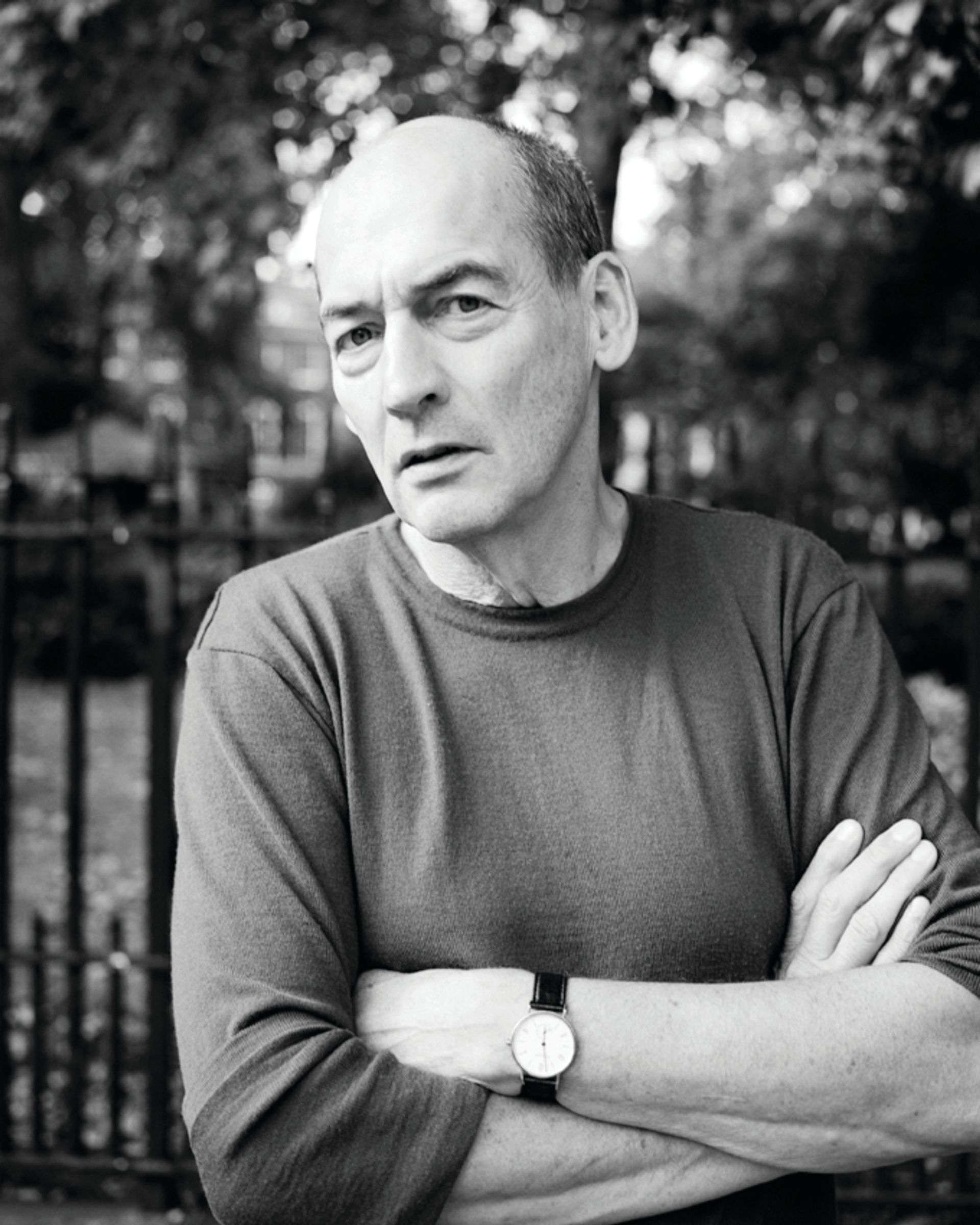

Rem Koolhaas, architect, founder of OMA architects

“It was a perfect project which, rather than initiating a new period, turned out to be the end of a period”

The Centre Pompidou was maybe the last moment that a museum competition won with that degree of abstraction, radicality and that degree of newness. It was more a hypothesis than a project and I think museum competitions since then have moved as far as possible away from that. The very model of a museum that the Pompidou offered has been avoided as much as possible by subsequent museum competitions, juries, clients and realisations.

Very soon after it opened there was a strong critique from the museum world, and the art world particularly, that the floor plates were undifferentiated, not divided into rooms and not offering ideal museum conditions—it was very far from the “white cube”. And not long after it opened, there were redesigns implemented that supposedly corrected those conditions. So it has been influential mostly in terms of what has been avoided in the museum world. It has had a very different effect on the museum world than on the architectural world.

It was the last time that a hypothesis won, and for me it was a totally euphoric moment, the euphoric evidence of what was possible in architecture. Therefore, maybe as a generalisation it showed an incredibly vigorous architectural model and an incredibly vigorous model of state involvement in the cultural sector, exactly at the moment that that vigour from the state and from architecture was becoming less powerful.

It’s been a very important project for me in the sense that many of our projects—and I would say our best projects—are mixtures of engineering and architecture, and that is what the Pompidou is. So in that sense, the engineering of the Pompidou played a big role in our architecture.

We now seem to be talking about the Pompidou only as a museum, but it was initially a hybrid of many different programmes and different conditions. Of course, that was a very 1970s mentality, inspired as much by Cedric Price’s Fun Palace as by anything else. A lot of that was, in the end, surrendered or sacrificed to the museum. On the whole, I think you can say it was a perfect project which, rather than initiating a new period, turned out to be the end of a period, perhaps. So that what could have been seen as an instrument for opening up a new territory in the end became a monument to a mentality that was unsustainable.

There were a number of ground-breaking exhibitions in the very beginning when Hultén was director and because it coincided very much with my own interests, I was very excited that the Pompidou had a particular relationship with Russia, or the Soviet Union. I remember, for instance, that the Soviet government—or maybe it was a combination of the [Malevich] family and the government—delivered to the Pompidou in 1979 and 1980 the plaster models—Tektoniks—that had been made by Malevich himself. They were too controversial to show in Russia and were then exiled to Paris. It was an astonishing moment where you could see those things for the first time. [The] Paris-Moscow [exhibition] was a total eye-opener.

Hans Ulrich Obrist, artistic director, Serpentine Galleries

“One goes with the other: the amazing building and the amazing programme”

The Pompidou was part of my lern- und wanderjahre. In the 1980s, as a teenager, I would always go to Paris. It’s the big city that one would always travel to by train from Switzerland. I would go there systematically as a teenager to see shows.

It’s an important moment to celebrate this great building by Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano and also celebrate Pontus Hultén, because one goes with the other: the amazing building and the amazing programme in Hultén’s laboratory years. He used, in such a brilliant way, this vision of a building as a radical event, a building as a happening; he played the building almost like a musical instrument. In those early shows like Paris-New York and so on, art, literature, dance, film—and, of course, music, with Ircam next door—were brought together. And that is the history of the avant-garde: those moments always went beyond the fear of pooling knowledge.

A view of the Pompidou’s ground-breaking 1985 exhibition Les Immatériaux Photo: Centre Pompidou-Mnam-Bibliothèque

Of the many epiphanies I have had at the Pompidou, one is an exhibition that I didn’t see: Les Immatériaux [in 1985]. But it has always inspired me, through the catalogue and through the images I have seen. It has proved a huge influence on my generation of artists. I’ve always had the catalogue, a collection of loose sheets, with me since I was a student, and look at it almost every day. It was organised by the philosopher Jean-François Lyotard together with Thierry Chaput [the director of the Centre de Création Industrielle] and it was a catalyst for many artists of my generation. It really anticipated our digital age; it looked at what it meant to move from material objects—because art history from the 19th century to the 1960s is very much a history of objects—to immaterial information technologies. It was a labyrinthine parcours, with one entrance and one exit, but then you could choose the way you went and the walls were flexible. Visitors could listen to radio transmissions, it was fluid, all kinds of disciplines met there; you could have painting but also astrophysics. A lot of our exhibitions, like Laboratorium in the late 1990s, or Cities on the Move [1997], were deeply inspired by Lyotard’s labyrinth.

Iwona Blazwick, director, Whitechapel Gallery “They were bold enough to have a thesis and ask questions through exhibitions”

The Pompidou pioneered these great argumentative shows, such as Magiciens de la Terre [1998], the much derided and controversial but tremendously influential show—for nothing else than the debate it raised about post-colonialism. There was the exhibition Féminin-Masculin in 1995, which was so pioneering in looking at sexuality, identity, psychoanalysis and in including so many women artists. Those courageous shows were bold enough to have a thesis and ask questions through the process of exhibition-making. They have been so influential for me and, I think, for a generation of curators like Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, the people who went on to do the big biennales and Documenta. They showed exhibition making as a kind of discourse, as a way of asking, what if? Or, how do we capture a zeitgeist? Or, what are the big issues?

Neil Dawson’s Globe (1989), from the Centre Pompidou’s Magiciens de la Terre show Photo: Centre Pompidou-Mnam-Bibliothèque

And the other thing was curators like Christine Van Assche and Catherine David, commissioning work for their collection—that was a first. They commissioned Mona Hatoum to make Corps étranger [1994], one of her best works, I think, and Stan Douglas’s Hors-Champs [1992], a fantastic work—they pinpointed really interesting artists. Christine Van Assche saw that moving image work was the future and they put in the money and the resources to make great new works which then went into the collection.

When I was at the ICA [in London], we worked with the Pompidou on an exhibition about Situationism: On the Passage of a Few People Through a Rather Brief Moment in Time. It was such a radical movement, so opposed to institutions, so it was very courageous of the Pompidou to embrace a movement so against everything they stood for. That was a really wonderful encounter, w here a giant museum worked together with a kunsthalle like the ICA; everything about it was radical, exciting, political, provocative.

Mona Hatoum, artist “Its exoskeleton and visible entrails give you a feeling of non-conformity and freedom”

I have always seen the Pompidou as a centre of innovation and experimentation. The absurdity of the building’s architecture, with its exoskeleton and its visible entrails, so to speak, gives you a feeling of being “outside the box”, and a sense of non-conformity and freedom to embrace the multidisciplinary and new media. I have seen so many great exhibitions there, it is difficult to choose just a few. The ones that stand out are the Joseph Beuys exhibition of 1994, especially the felt room installation Plight, the Gerhard Richter exhibition [Panorama, 2012], which was beautifully installed, and, the most recent highlight for me, the amazing presentation of Pierre Huyghe’s work [2013], which I visited several times.

The Pompidou have been very good to me, with a long history of support for my work. I was first approached in 1991 by Christine Van Assche, the curator of video and new media, to create a video installation for the Pompidou. I spent a lot of time working with their technicians in the belly of the Pompidou. In 1994, I was offered my very first museum solo exhibition in one of the street-level galleries, which they called Le Studio at the time. I showed the newly commissioned work, Corps étranger, which became emblematic of my work, along with two other large installations and a room of single-channel video works. This exhibition practically launched my career.

Twenty years later I was approached by the same curator to mount the largest and most comprehensive survey of my work to date. This time it took place in the beautiful large space on the sixth floor with its amazing panoramic view that inspired me to make a specific work for the space, Map (clear) [2015]. It was also the exhibition with the highest attendance I have ever had.

Philippe Parreno, artist “It’s a machine that produces form, and form produces collectivity”

Beaubourg opened in 1977 and I am 52, so you can imagine that I literally grew up with Beaubourg and what it represented. I used to hang around Beaubourg all the time. There is the Café Beaubourg nearby and Gilbert Costes the owner was nice to me when I did not have much. He proposed that I made a table for him; a table where I would scratch things and write things. He would keep the table as an artwork, and in exchange I would have free coffee and free food. So I used to spend a lot of time at Beaubourg, because it was a place where I could live. Beaubourg gave its name to a neighbourhood.

And then Beaubourg is also a public space, a place where you go in for free, whether or not you decide to go and see a show. It had all those ingredients of what I like in art, meaning the idea that it’s a public space and it’s a machine that produces form, and form produces collectivity—so there’s a sort of chain of sense in it. There was the idea that the building will be completely open to different contingencies and situations, a modular architectural space where the walls appear and disappear. The museum was a place not only to collect and present a collection, but to produce exhibitions. And one exhibition changed my life, Les Immatériaux by Lyotard. I am still haunted by that show, by the way it was made, the way it was produced, the fact that it was an exhibition not as a display of objects but a place to think, to produce thought.

More recently, Beaubourg became a monument to its own prestige, which is a very French thing; the French are very good at making their own statues. When I did a show there, it was really hard even to move a wall, so it had become static. The idea of Piano and Rogers was that it [Galerie Sud, the ground floor space] was completely open to the street—it was literally in the street except for windows, so people could see what was inside. But over time the Pompidou started to put in filters because they want people to pay to get inside, and it became an aberration. So what I did was the opposite: I cleared out the entire plateau, because it was polluted with walls that couldn’t move, to make it accessible to the street once again. So the blinds would go up and down as part of the show, but people would be able to see the exhibition from outside. All these things were ideas embodied within the architecture; it is full of ideas like that.

When I was given the Turbine Hall commission [Parreno’s Anywhen is at Tate Modern until 2 April] one of the first things I did was to go to see Herzog & de Meuron. And strangely enough, they told me that the starting point of the Tate Modern and the Turbine Hall was precisely the open space of Beaubourg. So Beaubourg still echoes, it has a really big resonance, even today.

Massimiliano Gioni, artistic director, New Museum, New York “It created the model of the truly interdisciplinary institution”

In my experience and memory, the Pompidou was the very first contemporary art museum that took on the idea of the audience as a mass phenomenon. And the fact that such an attitude emerged at the beginning of the 1970s and from two very young architects made the Pompidou a kind of strange relative of the transformations and hopes, utopias—and perhaps even the failures—of the 1960s. In its shameless embrace of technology and modernity, it also expressed an idea of art and culture as engines of change.

The square in front of the Pompidou and the fountain by Jean Tinguely and Niki de Saint Phalle did for art and culture and for Paris—and for many other cities, probably—as much as all the shows inside. They created a sort of amphitheatre for urban life. And I still remember how excited and afraid I was to be there for the very first time when I went to Paris alone as a teenager.

Every time I look at old installation photographs from legendary shows there I am always blown away by how radical and conventional they were at the same time. I remember, for example, that there were plants in the lobby of the Duchamp retrospective in 1977. That’s the fate for every radical institution. But it has continued to embrace the most diverse audiences and you can go any day and hang out in the library or the videotheque and still have a clear feeling of how much more than just a depot for art the Pompidou has aspired to be.

For me, it’s mostly through the books and catalogues that I have come to love the Pompidou (and its ghosts and memories). All the Paris-Moscow, Paris-New York etcetera catalogues, which you can still see in the libraries of anybody who has a decent sense of style and art history: those books were just incredible. As was the beautiful Duchamp retrospective book. Or Lyotard’s Immatériaux book. I remember always spending as much time in its bookstore as in the galleries.

Bruce Altshuler, Director, Program in Museum Studies, New York University “It was a perfect project which, rather than initiating a new period, turned out to be the end of a period”

I tend to think of two facets that made the Pompidou radical. One that is often remarked on, which is its move towards a more open, apparently democratic design for a large, broad public; a non-elitist institution reflected in the transparency of the architecture and the Place Georges Pompidou in front. Of course, it’s one of many moves in that direction in the US and the UK, etcetera. But it is the model of that.

Another aspect of its opening, which I am interested in, in terms of institutions and specific ways around content, is that it creates the model of the truly interdisciplinary institution, one composed of all these different departments. To me, that is extremely interesting, the way that was expressed in that great series of exhibitions curated by Pontus Hultén, starting with Paris-New York in 1977, exhibitions ranging across all areas of cultural history: visual art, music, architecture, dance, etcetera. It is the model of an institution that combines many different cultural areas, that’s truly interdisciplinary.

You see that in the exhibition Les Immatériaux, which came out of the Centre de Création Industrielle. It was often thought of as an art exhibition but it was wholly interdisciplinary. The structure of the exhibition was designed with this open, multi-directional plan and acoustic elements that would come on with long quotations from literature and philosophy, with these relatively obscure themes, although I don’t think the organisers thought that way. It began as a show of materials, and then it moved into this other realm. It’s an interesting example of a show that used an elitist language, in a way, but I think they probably believed there was something for everyone. And the public loved it because there was this interactive, technological element. It was both democratic and elitist at the same time.

"An extreme interpretation of a changing world" Renzo Piano looks back on his creation and how it influenced subsequent projects

When the Centre Pompidou opened in 1977, “it was the beginning of a revolution”, says the Italian Pritzker Prize-winner Renzo Piano. The museum’s architects—Piano, Richard Rogers, and Gianfranco Franchini—had a radical idea. They wanted to turn conventional museum architecture on its head by turning the building inside out. They had no idea that their design would shape approaches to museum building for the next four decades.

The team’s proposal was chosen from 681 submissions to France’s first international government-run architectural competition. The concept was inspired by the spirit of protest and democratisation that swept across the globe in late 1960s. “We thought, ‘You need to open museums to everybody’,” Piano says. “It was not us changing the world—it was the world changing by itself, and we made an extreme interpretation of that change.”

In 1977, the openness and flexibility exemplified by the exposed structural elements and the column-free gallery spaces were unprecedented. “Museums at that time were not what we see now,” Piano told us in a largely unpublished interview conducted in March 2015. “At the time, museums were still quite intimidating places for people.”

Now, Piano must reckon with the trends he created. “The pendulum went a bit too much to the other side,” he says. “Now, we almost see the opposite problem.” Some institutions are more interested in acting as social spaces than as homes for art.

“When I was young, and we were doing Beaubourg, our duty was to break the rules and to open museums to everybody. Now, I am 78, and the duty is to defend the fact that the museum is fundamentally a place where you can of course meet people, but also where you need to enjoy art,” Piano says. “Of course, we preserve the openness and accessibility that we started to preach 40 years ago. But we also have to defend more and more the silence.” — Julia Halperin