The death of Richard Rogers opens up his contribution to architecture, urbanism and their perception and politics, to a review that will no doubt continue for many years. His life story was made public, in the authorised version, in Bryan Appleyard’s biography of 1986, marking the completion of Rogers’s new headquarters building for Lloyd’s of London, and has been repeated in different versions since.

Dyslexic, displaced, nurtured by devoted Anglo-Italian parents far from his native Florence, Rogers reached manhood with a mixture of self-doubt and self-assurance. Contact with his father’s first cousin Ernesto Rogers, a leader of Italian architectural thinking, shaped the direction of his career. Rogers was always the leader of a gang, and gathered those who could make up for his own deficiencies (including an inability to draw). He emerged from study at the Architectural Association, in London, in something close to his finished form.

With Su Brumwell, his first wife, at his side, he won a two-year scholarship to Yale. Norman Foster was another scholar, and they acknowledged the radical thinking of their teacher Serge Chermayeff, whose contacts from England in the 1930s intersected with the circle of abstract artists and scientific/political thinkers supported by Su’s father, Marcus Brumwell, a noted champion of British Modernism in art and design. When Marcus commissioned designs for a house in Cornwall from Ernst Freud, Rogers was furious at not being asked and, on their return from the US, he and Su, in partnership with Foster and sisters Georgie and Wendy Cheesman, set up their practice Team 4 to produce the small but ingenious retirement and holiday home, Creek Vean, in Cornwall, for Su’s parents.

Rogers wrote to the architect and artist Humphrey Spender that the ideal house ought to allow for outdoor sex in privacy

Team 4 was short-lived—as Appleyard says, “two powerful personalities… had burnt out their capacity for cooperation”. The travails of dealing with conventional construction prompted both to dispense with “wet trades” and build instead with metal and glass, not in the sober crypto-classical manner of Mies van der Rohe, but with Pop art colours and broad, undifferentiated internal spaces, given a trial run with the Reliance Controls building at Swindon. In 1967, Richard and Su Rogers, now working together as an adjunct of Marcus Brumwell’s Design Research Unit, conceived the Zip-Up House, and realised the concept in bright yellow steel frames, at 22 Parkside, Wimbledon, for Richard’s parents, and at Ulting, Essex, for the photographer and artist Humphrey Spender. In both cases, the house and separate pavilion-studio plan derived from Chermayeff’s studies of single-storey courtyard houses as a universal solution to replace suburban norms. Rogers wrote to Spender that the ideal house ought to allow for outdoor sex in privacy.

The Centre Pompidou in Paris

Rogers was introduced to a like-minded Genoese contemporary, Renzo Piano, and they produced an abortive scheme for a stand at Chelsea football stadium, in west London. Then, Ted Happold, who was leading the “Structures 3” team at Ove Arup engineers, decided it might be fun to submit an entry to the competition for a new multifunctional modern art museum in Paris, the response of President Georges Pompidou both to the redevelopment of the Les Halles quarter and the evénéments of 1968. The brief, written by the competition jury chairman, Jean Prouvé, called for an unconventional anti-museum. Happold thought Piano and Rogers might be right for the job, although the latter’s diffidence almost prevented it happening. Their entry, one out of 681, was a concept and image, largely drawn by Gianfranco Franchini, rather than a building. The architectural historian Francesco Dal Co has described how, while its anti-monumental character appealed as “linear, flexible, functional, multi-purpose and simple… actually it was none of these terms.”

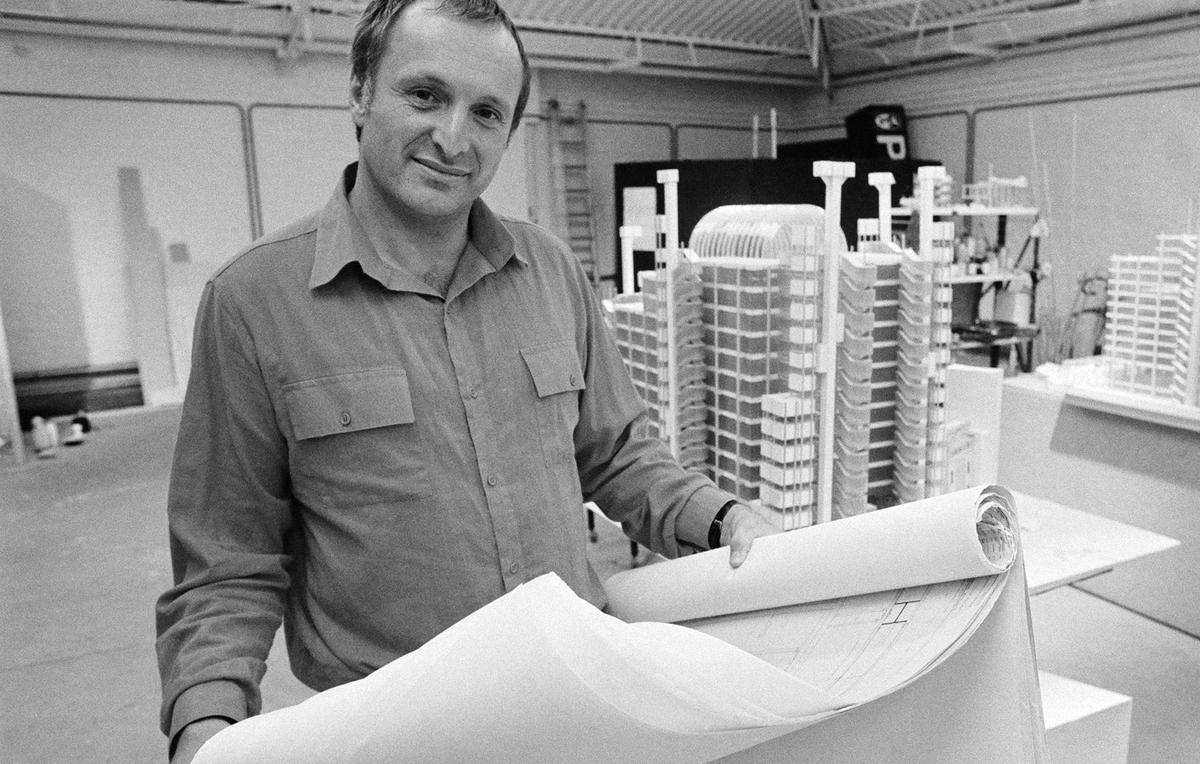

The stuff of legend

The near-miss of dispatching the roll of competition drawings, the shock of the news of victory, and the twists and turns of turning the concept into a structure are the stuff of legend and two books. A museologist might agree with Kenneth Frampton’s verdict of “a case of under-provision of wall surface and over-provision of flexibility”, but while the collection of the old Musée d’Art Moderne at the Palais de Tokyo was at its core, the ancillary activities of open-access research library and temporary exhibition space, initially programmed by Pontus Hultén, were equally important to its identity.

[Centre Pompidou], rather than initiating a new period, turned out to be the end of a periodRem Koolhaas, architect

At the 40th anniversary point, the architect Rem Koolhaas declared in The Art Newspaper that “It was a perfect project which, rather than initiating a new period, turned out to be the end of a period.” Arguments continue over the need for major overhauls of the building at intervals of about 25 years, but since the opening in 1977, the Centre Georges Pompidou has overcome most nay-sayers.

The foundations of Richard Rogers Partnership and its egalitarian working methods were laid with a multi-talented and harmonious team, including the partners Mike Davies, Laurie Abbott, John Young and Marco Goldschmied, and the inspired Arup engineer Peter Rice.

Lloyd's building in 2011, designed by Richard Rogers

Lloyd’s of London opportunely filled the gap in the work schedule when commissioned in 1977, a project committed to a tighter brief in which flexibility again played a part. With its knobbly exterior of service towers, WC pods and wall-climber lifts, it was the anti-type of the smooth Miesian tower slabs by Gollins Melvin Ward from ten years before facing it across Commercial Union Plaza, while inside the central atrium and open serviced floors anticipated the future direction of office planning.

By the time Lloyd’s was unveiled in 1986, Rogers and his building had become players in architectural culture wars, following the opening shots by the Prince of Wales two years before, in which Rogers’s National Gallery competition design, although not the selected choice, appeared to be a target. In 1984 Rogers produced a lengthy inquiry statement defending the Mies slab proposed by Peter Palumbo for the projected Mansion House Square, despite the building representing everything that the Lloyd’s building had superseded.

A new wave

While continuing to berate conservation, Rogers began to develop urban schemes for London that largely left older buildings in place while changing how they could be enjoyed by pedestrians in traffic-free public spaces. This form of cognitive dissonance may only have been an amplification of what most architects require to function, but posterity will ask whether it was counterproductive for winning the culture war. The machine imagery of the early buildings was painstakingly hand-made; Rogers’s 1994 scheme to cover the South Bank Centre in an open-sided glass “wave” was supposed to generate, in his memorable marketing phrase, “the climate of Bordeaux”, but could never have tempered the winter winds off the Thames. And for an advocate of public space and universal good housing, his practice designed a surprisingly large number of luxury flats for very rich people.

Yet Rogers’s collaboration with Ken Livingstone, mayor of London, and Tony Blair, when prime minister, produced a sequence of interventions to reduce traffic and stimulate regeneration of a more benign kind and publicise the merits of high-density housing. If Londoners can now take the “cappuccino culture” of their streets for granted, they may have an Anglo-Italian architect to thank for it.

In the 35 years since completing Lloyd’s, the Rogers partnership has produced landmark buildings around the world including the Millennium Dome in London (1996-99); the Senedd Cymru in Cardiff (1998-2005); Terminal 5 at Heathrow Airport (1988-2008); the extension to the British Museum (2007-14); and 3 World Trade Centre in New York (2006-18).

The practice was based for many years by the river Thames at Hammersmith, where Rogers’s second wife, Ruth Elias, opened the River Café with Rose Gray, in 1987. This location provided Rogers with the name of his peerage, Lord Rogers of Riverside. In 2007, he arranged a succession plan, renaming his practice Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners in acknowledgment of two long-standing younger collaborators, with a new London base in the practice’s own Leadenhall Building, known as the Cheesegrater.

Richard George Rogers; born Florence 23 July 1933; chair of trustees, Tate Gallery 1984-89; RIBA Gold Medal 1985; knight 1991; created Baron Rogers of Riverside 1996; Stirling Prize 2006 and 2009; Pritzker Prize 2007; Companion of Honour 2008; married 1960 Su Brumwell (three sons; marriage dissolved), 1973 Ruth Elias (one son, and one son deceased); died 18 December 2021.