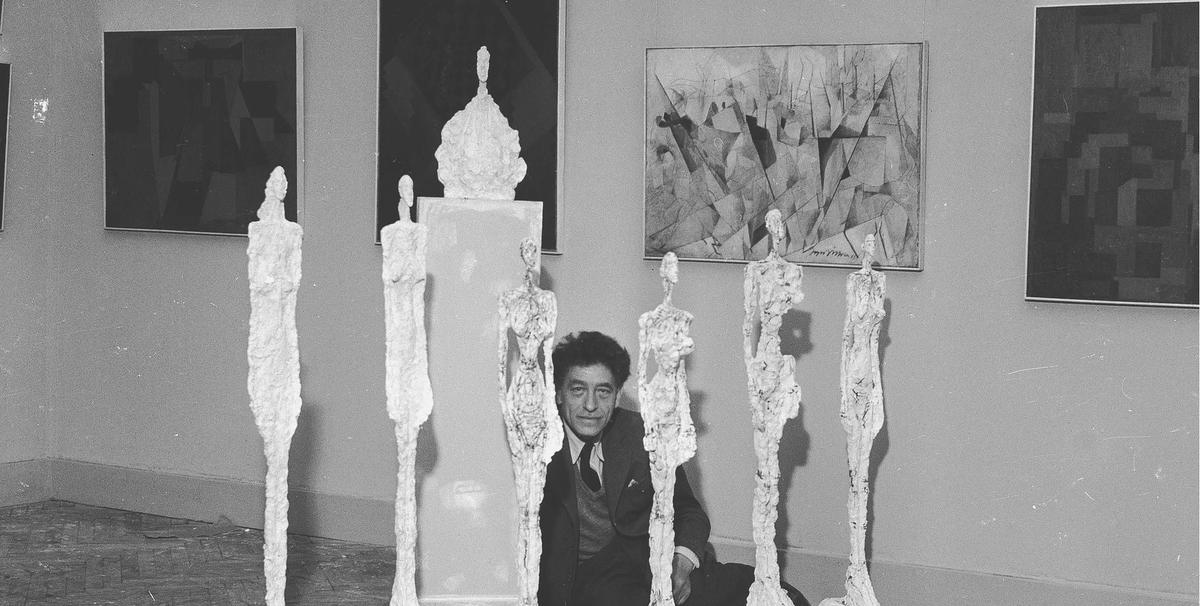

A group of six tall spindly female nudes created in plaster by Alberto Giacometti for the Venice Biennale in 1956 are to be reunited for the first time in 60 years at Tate Modern this spring. The Women of Venice plasters will be shown alongside two further sculptures from the same series, which Giacometti unveiled at the Kunsthalle Berne that year.

Giacometti’s emaciated bronze figures are considered among the most important sculptures of the 20th century–his 1947 L’Homme au doigt (Pointing Man) became the most valuable sculpture to sell at auction in 2015, fetching £91m. But his plaster and clay works are less well known, something Tate Modern hopes to redress.

“We always think of Giacometti as an artist in bronze, but of course bronze was the final outcome of a process that began with more informal, liquid materials,” says Frances Morris, the director of Tate Modern and a co-curator of the retrospective (10 May-10 September). “He started making bronzes because people wanted to collect his work, but he wasn’t terribly interested in the casting process, which his brother Diego oversaw.”

It took Giacometti roughly three weeks to mould each of the Women in Venice figures in clay before casting them in plaster and reworking the surface with a knife. He then painted some of the sculptures in red and black–details that are lost in the bronze versions.

The plasters, modelled on Giacometti's wife and muse Annette, are being restored ahead of the show by the Paris-based Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti–one of the foundation’s most ambitious conservation projects to date. “After the exhibition the plasters will go back to Paris where they will be available to scholars, but they won’t tour,” Morris says.

Other revelations in the exhibition include Giacometti’s deep engagement with art history and his relationship with decorative art. “He had an extraordinary library, which he would return to every day,” Morris says. “There’s barely a page that he didn’t annotate with drawings. He was constantly looking at African, ancient Egyptian, Cycladic and Renaissance sculpture; he saw the world through examples of the past.”

More than 250 works spanning five decades are to go on show, from early works such as Head of a Woman (Flora Mayo) (1926) to classic bronze sculptures such as Walking Man I (1960). It will also include examples of Giacometti’s Surrealist and abstract works, which were heavily influenced by African sculpture.

There has been a long association between the Tate and Giacometti dating back to the 1940s when the then director John Rothenstein made the “bold decision”, Morris says, to buy a bronze, Pointing Man (1947), just two years after it was created. The acquisition put the Tate ahead of French museums, which were yet to collect Giacometti’s work. The purchase, which demonstrated the Tate’s “early commitment to risk taking and innovation”, paved the way for the 1965 exhibition of Giacometti’s work at Tate Gallery.

Morris describes the retrospective as a “long time coming”, noting that Giacometti’s generosity following his 1965 exhibition allowed the Tate to acquire eight sculptures and two paintings for just £30,000. “We are indebted to Giacometti for helping us with our holdings and contributing to our history,” Morris says. “This retrospective is a posthumous thank you.”