Gustave Courbet’s The Origin of the World (1866) a painting of a woman’s “lower groin” (bas-ventre), as the writer Edmond de Goncourt coyly described it in June 1889, is as beautiful as it is brazen. Courbet’s model is portrayed only by her vulva, her thighs parted so as to reveal vaginal lips, offset by black pubic hair, a white sheet, and the pink flesh of her lower breasts. As the title confirms, Courbet pays homage to the origin of life and the world as we know it, but in the process he stages a call to arms for a radically new realism too.

The painting has remained closely guarded by the Musée d’Orsay since its acquisition in 1995, and so the recent public and critical attention is long overdue. Where Courbet has been rightly viewed as a key painter in the birth of modern art, the time has come to appreciate just how much he revolutionised the long tradition of the female nude.

Gustave Courbet was born on 10 June, 1819, in Ornans near Besançon in the French Jura and he died on 31 December 31, 1877 in La Tour-de-Peilz in Switzerland. It is said that his mother gave birth to him under an oak tree, on her way from Flagey to her parents’ home at Ornans. The story is appealing when considered alongside The Origin of the World: perhaps Courbet was destined to bring nature, woman, and art together in a powerful new way.

However, the painting goes beyond the autobiographical and is best viewed as a manifesto offering an allegory of sexual pleasure. It follows perfectly from Courbet’s The Artist's Studio, a real allegory summing up seven years of my artistic and moral life (1854-55) in which Courbet portrays himself painting a landscape with his brush in mid-air. His back is to a naked model and there is a young boy by his side, both fascinated by his skill and forming an Oedipal triangle with the artist. All around, his studio is littered with characters that helped define the painter. As he explained in a letter to his art critic friend Champfleury, “friends, fellow workers and art lovers” are on the right, including Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Charles Baudelaire, and Champfleury himself, while, on the left, we see “the world of commonplace life”, including a merchant, a priest, and a beggar woman. The Artist’s Studio insists that the artist had to be at the throbbing centre of society and had to portray it honestly. In a letter to the editor of the Messager de l’Assemblée on 19 November 1851, Courbet had asserted that he was “not a socialist … but a democrat and a Republican as well—in a word, a partisan of all the revolution and above all a Realist … for ‘Realist’ means a sincere lover of the honest truth.”

The Origin of the World goes further again in this honest vision of the real. The viewer becomes part of the tableau vivant, drawn so close that the perspective is almost gynaecological. Many artists before Courbet had staged peek-a-boo trysts with the viewer either by displaying the nude in nature in such a manner as to give the best view of her unclothed figure, despite her supposed virtue and innocence, or by displaying her as the very embodiment of vice, cheekily looking out of a boudoir with blushing nude buttocks. Courbet’s radical move lay in portraying the pudenda without any mythological, historical or moralistic narrative, even in a state of arousal.

He was not the first to focus on the vulva in this manner—it had already enjoyed a long history of explicit representation from Sheela na Gig carvings in Celtic Ireland to Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical drawings and 19th-century erotic lithographs by Achille Deveria and Octave Tassaert. Scholars such as Dominique de Font-Réaulx and Thierry Savatier have also directed attention towards the erotic stereographic works of Auguste Belloc (1800-1867) as possible sources of inspiration for Courbet’s painting, as he embraced the new medium of photography and used it for his art practice. However, if Courbet looked to erotic photographs as visual aids he did not reproduce them. It is his technique with brush and palette knife, and the very materiality of his paint, that renders the work and its eroticism so modern.

The Origin of the World has enjoyed a rather sensationalist history and Courbet’s subject-matter has fuelled the idea of the artist and the collector of art as secret fetishists with obsessive desires. Courbet painted the work for the Ottoman diplomat and collector Khalil Bey (1831-1879)—“a Moslem who paid for his whims in gold”, according to Maxime du Camp in his history of the Paris Commune, Les convulsions de Paris (1889). Bey’s collection also included Courbet’s The Sleepers (1866), an image of lesbian lovers, one with red hair, the other with dark hair, their bodies intertwined, and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ The Turkish Bath (1862) where a harem of curvaceous female beauties are staged for visual pleasure. In his book Trois dîners avec Gambetta, edited by his son Daniel Halévy in 1929, the French author Ludovic Halévy recounted seeing The Origin of the World at a party in Khalil Bey’s home, also attended by Courbet. Halévy reports that in response to his company’s many admiring comments on the work, Courbet replied “You think this beautiful …and you are right. …Yes, it is very beautiful, and listen, Titian, Veronese, Raphael, I myself, none of us have ever done anything more beautiful.” Unsurprisingly, in the public mind, Courbet was strongly associated with the daring painting: in a famous caricature of the artist for the cover of the June 13, 1867 edition of the weekly satirical magazine Le Hanneton, Courbet stands with a beer in one hand and a palette in the other, while a large picture of a fig leaf is prominently displayed behind him.

When Bey’s collection was sold in 1867, The Origin of the World was not included in the sales catalogue but resurfaced later, in the home of the Hungarian Jewish collector, Baron Ferenc Hatvany. He had purchased it from the Bernheim-Jeune gallery in Paris in 1913. Surviving two world wars, The Origin of the World was then sold at auction for 1.5 million francs in 1955 to the renowned psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan and his wife Sylvie Maklès, an actress and the ex-wife of Georges Bataille.

The manner in which each successive collector displayed the work has also intensified its erotic reputation. Indeed, Linda Nochlin once described it as an “Origin without an Original” (October, no 37, Summer 1986) because its provenance has been the subject of so much intrigue. When displayed, The Origin of the World was typically covered in some way by its owners, adding a further titillating layer to Courbet’s canvas. It was veiled under a green curtain when in the collection of Bey, under a painting of a church in snow by Courbet when viewed by Edmond de Goncourt in the antique shop of Antoine de la Narde in Paris in 1889, and it was kept under a painting of a nude on a wooden panel by Surrealist André Masson when Pablo Picasso, Dora Maar and James Lord saw it in Jacques and Sylvie Lacan’s country house in Guitrancourt. Masson’s painting was perhaps the most eloquent of screens as it was produced specifically for Courbet’s work - Erotic Landscape (1955) displays a truncated female nude whose nubile contours echo those of mountains. It reminds us that Courbet’s landscapes have an erotic potential too, as, for example, in the suggestive dark cavern in the foreground of The Source of the Loue (1864).

Rumour has also surrounded the identity of the model for The Origin of the World, usually said to be the beautiful Irish woman Joanna Hiffernan. She was introduced to Courbet by James Whistler in the seaside resort of Trouville in 1865. Whistler enjoyed the contrast between white clothing and Jo’s fiery red hair in many of his portraits of her, including The White Girl (1863). However, where the English painter gave Jo a rather awkward, pubescent look and always kept her at arms length, Courbet’s Portrait of Jo, the Beautiful Irish Girl (1865-66) emphasised her physicality and self-awareness, even using the mirror as a symbol of vanitas to highlight the ideas of looking and being looked at. The falling out between Whistler and Courbet after that seaside sojourn and speculation over the sexual as well as artistic sharing of the Irish model has become the stuff of legend. As recently as February 2013 a cover story in Paris Match claimed that the supposedly missing upper half of the painting had been discovered, depicting a red haired beauty, although the story was soon called into question by forensic analysis.

Notwithstanding such intrigue, the identity of female artists’ models has traditionally been a minority concern while the master painter of the work has won the critical acclaim. In The Origin of the World, not only is the model an anonymous torso, but the female sex is naked, available and framed looking down from a height. Hence, Courbet seems to place the viewer in the shoes of the master—from a Freudian perspective, this is a close up which might be read for its privileging male sexual desire and fear. It restages what Freud described as a seminal moment in every male’s development when the little boy looks up his mother’s skirt and realises that her genitals are quite different from his own. However, whilst it is tantalising to view Courbet’s painting in light of Freud’s idea of castration anxiety, to do so would be to foreclose the work’s erotic and revolutionary potential. If we view it as a glorious celebration of woman, open to the male or female gaze, or even as an image of auto-eroticism, we can better explain its cultural impact.

In a 1959 interview, Marcel Duchamp declared that Courbet’s revolution was a visual one, demanding a physical reaction and having “not much to do with the brain”. His installation Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas (1946-66) is undoubtedly a homage to Courbet, staging the exposed vulva of a reclining female nude in a startlingly confrontational manner typical of the Dadaist: the viewer witnesses the work by peeping through two small holes cut in a wooden door at eye level, creating an intensely private encounter with the erotic work. For Duchamp, Courbet also presaged the Abstract Expressionists in his gestural brushwork and tactile intensity. Certainly, without looking back to Courbet, one cannot appreciate Willem De Kooning’s visceral use of paint or his approach to the female form in The Visit (1966-1967).

Subsequently, generations of women artists have added a further layer to our appreciation of Courbet’s remarkable painting from feminist “vulvic art” of the 1970s to contemporary installations. Carolee Schneemann’s Interior Scroll (1975), Hannah Wilke’s Venus Envy (1980), Sherrie Levine’s After Courbet: 1-18 (2009), and Pilar Albarracín’s L’Origine du Nouveau Monde (2012), all subvert male artists’ obsessive framing of the female vulva whilst reclaiming it and reframing it for themselves.

To one degree or another, Courbet’s vulvic image paved the way for this progressive return of the repressed and the call to make desire not just visible, but egalitarian.

Private Nudes, Public Masterpieces Works originally made for the enjoyment and titillation of patrons that have since become linchpins of great museum collections

Titian, Venus of Urbino (1538, Uffizi, Florence)

Painted for the Duke of Camerino, Guidobaldo della Rovere, possibly to celebrate his 1534 marriage, Titian’s nude brings Venus indoors and, by making a maid and lady visible in the chamber behind her, domesticates this mythological beauty. The composition is based on Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus (c1510), with one hand coyly covering the genitals but as such, of course, the viewer’s eye is actually drawn to that erotic spot. Details such as her jewellery and flowers accentuate her charms, whilst the faithful dog symbolises fidelity. However, it is her eyes that seduce as they meet those of her admirer, staging an erotic dialogue between the female and male. As the work was intended as an instruction piece for the Duke’s young bride, Giulia Varano, and as the model has been identified as a well known Venetian courtesan with whom Titian used to dine, Angela del Moro, the art of seduction is perhaps presented as an essential element of the role of the wife.

Diego Velázquez, The Toilet of Venus/ Rokeby Venus (1647-51, National Gallery, London)

Velázquez’s nude is said to have been painted for Don Gaspar de Guzman, the Count-Duke of Olivares (1629-88), who was Philip IV’s prime minister between 1621 and 1643. As well as a powerful political figure, he was a passionate collector of art and a bon viveur, lending authority to the idea that he would have commissioned such a titillating nude. In Catholic Spain, painters were dissuaded from drawing from the nude model. In his Arte de la Pintura Pacheco, Velázquez’s teacher and father-in-law, wrote that the artist should only paint the face and hands of a female after nature—everything else should be painted from ancient and modern statues, drawings, and engravings to ensure the ideal was achieved. The mirror is employed here as a symbol of vanitas, as a metaphor for the passing of time and, by extension, of beauty. Its presence, especially in the hands of a Cupid, may speak to the transience of love, or, on an even higher moral ground, to the superiority of true love over base desire. It is a detail which also lends erotic intrigue to the work as we see only a sketchy image of the model’s face and as it still does not reveal her beautiful front—an element accentuated by the Count-Duke in pairing it with a 16th-century painting of a nude in a landscape, seen from the front.

Francisco Goya, Naked Maja (1795-80, Prado Museum, Madrid)

Goya’s Naked Maja was first documented in the collection of Manuel Godoy in 1800. When it and a companion image titled The Clothed Maja were confiscated by King Fernando VII in 1813 they were labeled “Gypsies”. According to J. F. de Bourgoing, the French Ambassador to Spain writing in 1788, the maja was “the most seducing priestess that ever presided at the altars of Venus”. Goya portrays his reclining nude in this light, with flushed cheeks, bold expression—she has no shame in her nudity. In fact, she seems to enjoy the power it gives her. Goya may be fusing the erotic and political here as it was rumoured that the model was his patron the Duchess of Alba, though she has also been identified as Pepita Tudó, who became Godoy’s mistress in 1797.

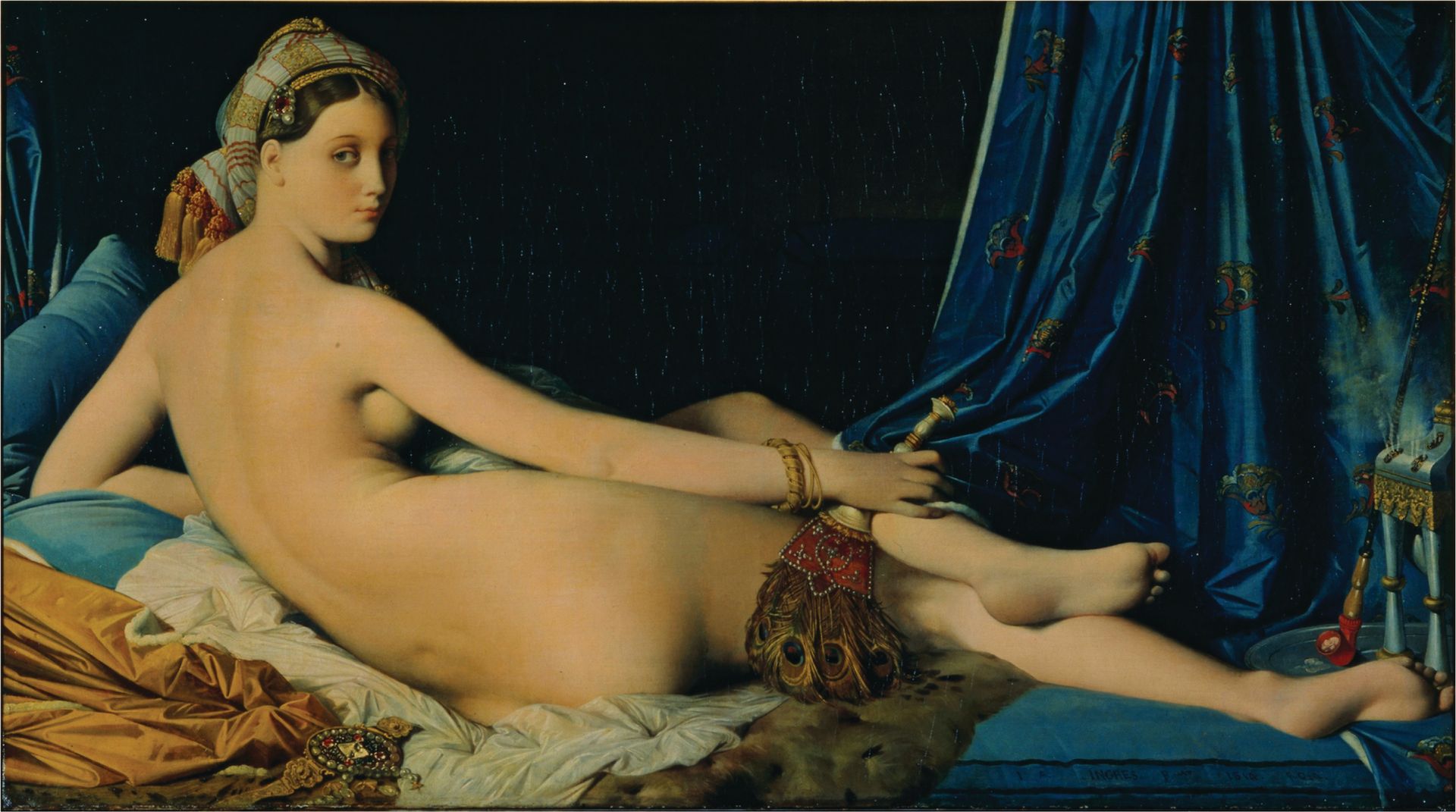

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque (1814, Louvre Museum, Paris)

Caroline Murat, Napoleon Bonaparte’s sister and the Queen of Naples, commissioned this painting in 1813, though by the time she received it, her kingdom had collapsed. It was intended as a pendant for a painting her husband Joachim Murat had purchased in 1809, a life size nude seen from the front titled The Sleeper of Naples. The idea that this pairing played to both a female and a male patron’s erotic tastes is tantalising, though it was typical of Renaissance art and its legacy through to the 19th century—nudes painted from a variety of perspectives demonstrated an artist’s skill while also allowing the unclothed body to be enjoyed from every angle. Ingres stages his nude in a very contemporary fashion by transposing the traditional, mythological nude to the imaginary Orient. Her supine form, almost Mannerist in style and anatomical inaccuracy, exaggerates the erotic appeal of the back and half visible breast, whilst her pearly skin is enhanced by the many colours and textures around her—velvet, fur, silk, peacock feathers. As an odalisque, she is unapologetically displayed for the viewer’s enjoyment; she is a concubine, a sexual slave whose life in a harem is hedonistic, as suggested by the perfume burner and opium pipe at her feet. The work flatters not only the male gaze but also the imperialist gaze and its civilising mission.

• This article appeared in our October 2014 print edition

• Read our most-read story of 2016