Westkunst, Kasper Koenig’s sprawling, contrarian and magisterial show of paintings from the 1930s to the 1980s, was our introduction to late Picabia. In the giant exhibition hall where the show took place, Picabia’s slightly unhinged-feeling paintings of the 1930s and 1940s came as a shock to those who knew only his early Cubist paintings—which is to say, nearly everyone in 1981.

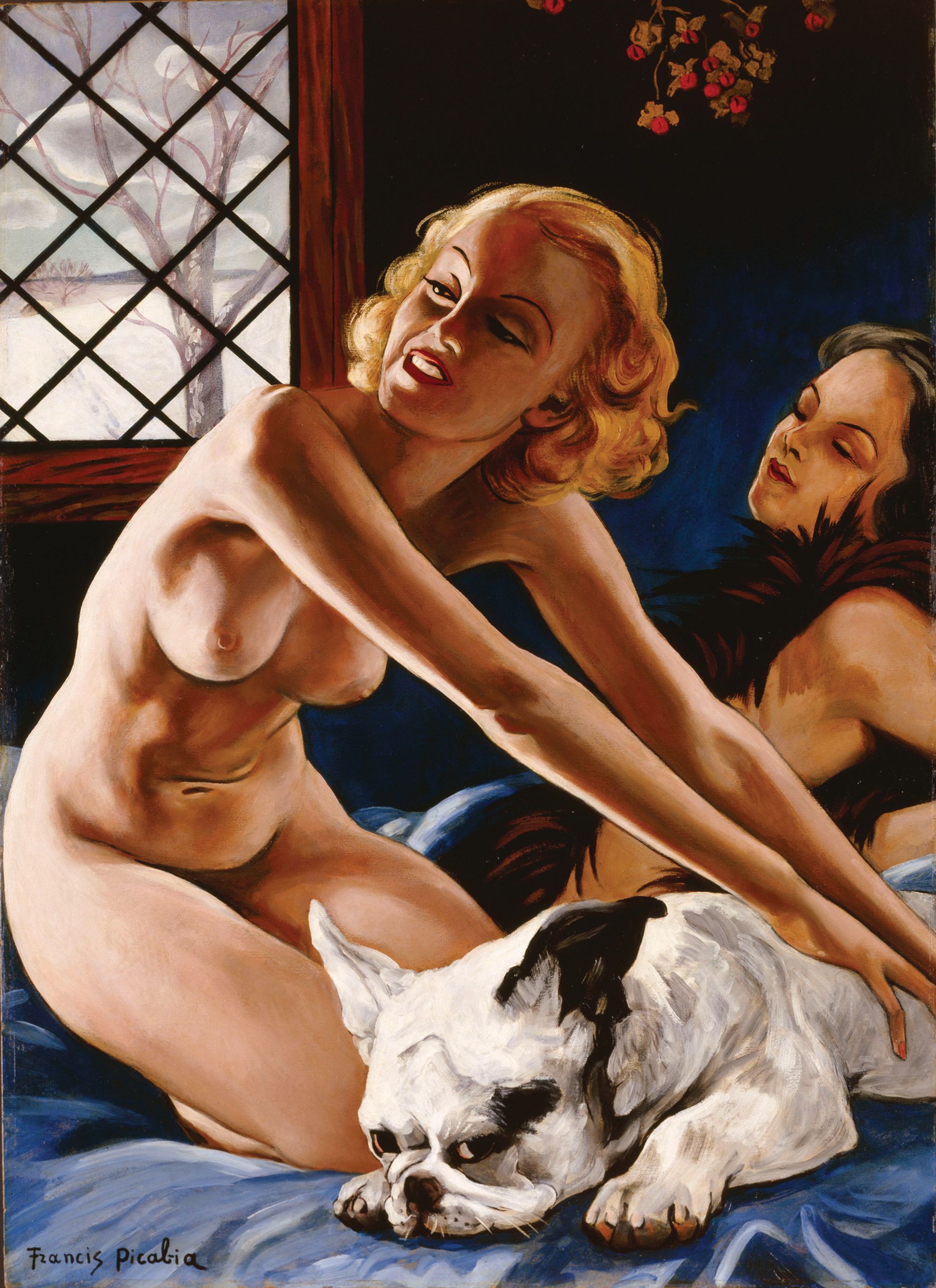

Picabia, if he was taught in the schools at all, was a footnote in the social history of the avant-garde; a sportif playboy and Dadaist provocateur who helped give the teens and early 1920s their savour, but hardly someone to be taken seriously as a painter. As I remember it, Kasper had installed a single large room with works from the late 1930s to early 1950s, mostly realistic scenes painted from photographs—female nudes, nudes with dogs, nudes with eroticised flowers, mixed-gender nudes (Adam and Eve), bullfighters and flamenco dancers all rendered in a lurid, heavily outlined and varnished style that was, even at the time of their making, a good 40 years out of date. The look of those late paintings leans heavily on a use of line—alternately elegant or crude—that Picabia had cribbed from Lautrec and Picasso. A cursive brush mark becomes an eyebrow, or a plump mouth, or any other part of a face. He had something of the sign painter’s way with a brush, attentive to the way an image could be simplified into a sign.

Brazen provocations When Picabia turned his hand to realism—basically a system in which volumetric form is defined by contrasts of light and shadow—he kept his penchant for outlining as a kind of graphic stimulation, and the mash-up of volume plus outline gives the paintings of the 1930s and 1940s a brazen, provocative feeling. At the time, no one had seen anything like them.

Picabia’s sensibility, though newly seen, already felt familiar in a way that was hard to account for. Melodramatic and full of unlikely juxtapositions, the somewhat ham-handed illustrational way of painting, with its chiselled brush strokes alternating with little curlicues, and the unabashedly erotic second-hand imagery presented with sincere interest and theatricality—all that made sense to me in a way that was hard to account for. His pictures struck a strange, dissonant chord that coincided with the general collapse of formalist pieties. I had never before seen painting as untethered to notions of taste or intention; there was no way of knowing how to take it, or whether even to take it seriously at all. The work was so undefended—it was exhilarating.

What was going on? For one thing, this was painting made during a collapse of authority. The war had scattered the avant-garde to the winds, or at least to America. Picabia decamped to the south of France in 1941 and sat out the Occupation in relative isolation. Funds were running low, an inheritance from his mother having largely been spent on the high life, racing Bugattis and collecting African sculpture. Picabia turned to girlie magazines as source material and, in one of the strangest intertwinings of art and commerce, sold a quantity of the resultant paintings to an Algerian businessman, who used them to decorate brothels in North Africa. One can only imagine. Whatever the motivations, what Picabia produced over the last 15 years of his life really had no precedent—and not much follow-up until the 1980s.

After Westkunst, Picabias from the late 1930s and 1940s started to turn up here and there, mostly in German galleries—Hans Neuendorf and Michael Werner mainly, but also at Rudolf Zwirner and a few others. As soon as I could afford it (they were not expensive), I bought one. Mine was a portrait of the French actress Viviane Romance (1939). It was clearly painted from a photograph: a trashy-looking redhead in a slip glancing over her shoulder at the viewer, with wavy hair and bright red lipstick, a heavy vamp look in her eyes. It was painted on a cheap board, and thickly varnished to boot—a real mess. Sadly, the painting disappeared in a divorce and I have no idea where it is now. It hung for years in my living room as both a compass point and a dare: I bet you can’t make something as discordant and unsettling as this!

A number of the painters I started out with were interested in Picabia’s transgressive taste; it was reassuring to know another rebel in the field. He seemed to foreshadow Sigmar Polke’s early work, and you can see his influence on Julian Schnabel, Francesco Clemente, Martin Kippenberger, Albert Oehlen and myself, among others. Liking Picabia’s work in 1981 or 1982 was almost an affront to the people who had championed, say, Robert Ryman’s all-white paintings. Every generation must feel some version of wanting to correct the story; to extricate painting from the narrows and constrictions of theory, and letting the air out of the story of linear progress had been our mission in a way. We wanted to create our own precursors.

Aesthetic, satirical or camp? The work of Picabia’s that feels most alive to me now is the figurative paintings, which were made from photographs first seen in nudist magazines of the time like Paris Sex Appeal. Sometimes the paintings are a direct translation of the photographs; others are collaged together from different poses. He painted himself into several of them, a satyr with flowing white hair and white teeth. It’s hard to say if their main attraction is aesthetic, satirical or camp—or a comingling of all three. Some pictures are so detached and schematic, painted with such indifferent technique, as to feel a bit hollow, as if his attention were elsewhere. But in pictures like Adam and Eve (around 1942), Women with Bulldog (around 1941) and Woman with Idol (around 1940-43)—and many others from that period—Picabia found the right container for his instincts. Those paintings make me deliriously happy; they sing. It’s amazing they exist.

• David Salle is an artist and the author of How to See: Looking, Talking and Thinking about Art, published by W.W. Norton & Company. This is an edited version of Picabia C’est Moi, which also appears in the catalogue of the exhibition Francis Picabia: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction (Museum of Modern Art, New York, until 19 March 2017). The show is organised by MoMA and the Kunsthaus Zurich