Asking a veteran conservator or museum professional where they were when the Arno River burst its banks 50 years ago this month, submerging the historic centre of Florence under 18 billion gallons of filthy water, is akin to asking someone what they were doing when Neil Armstrong walked on the moon. The flood was a pivotal moment in the history of conservation in terms of the development of new methods and techniques, key lessons learned, the formation of lasting relationships and, significantly, attracting a younger generation to the field. It is being marked by a series of events in Florence and Venice (which also sustained extensive damage).

Catastrophic destruction

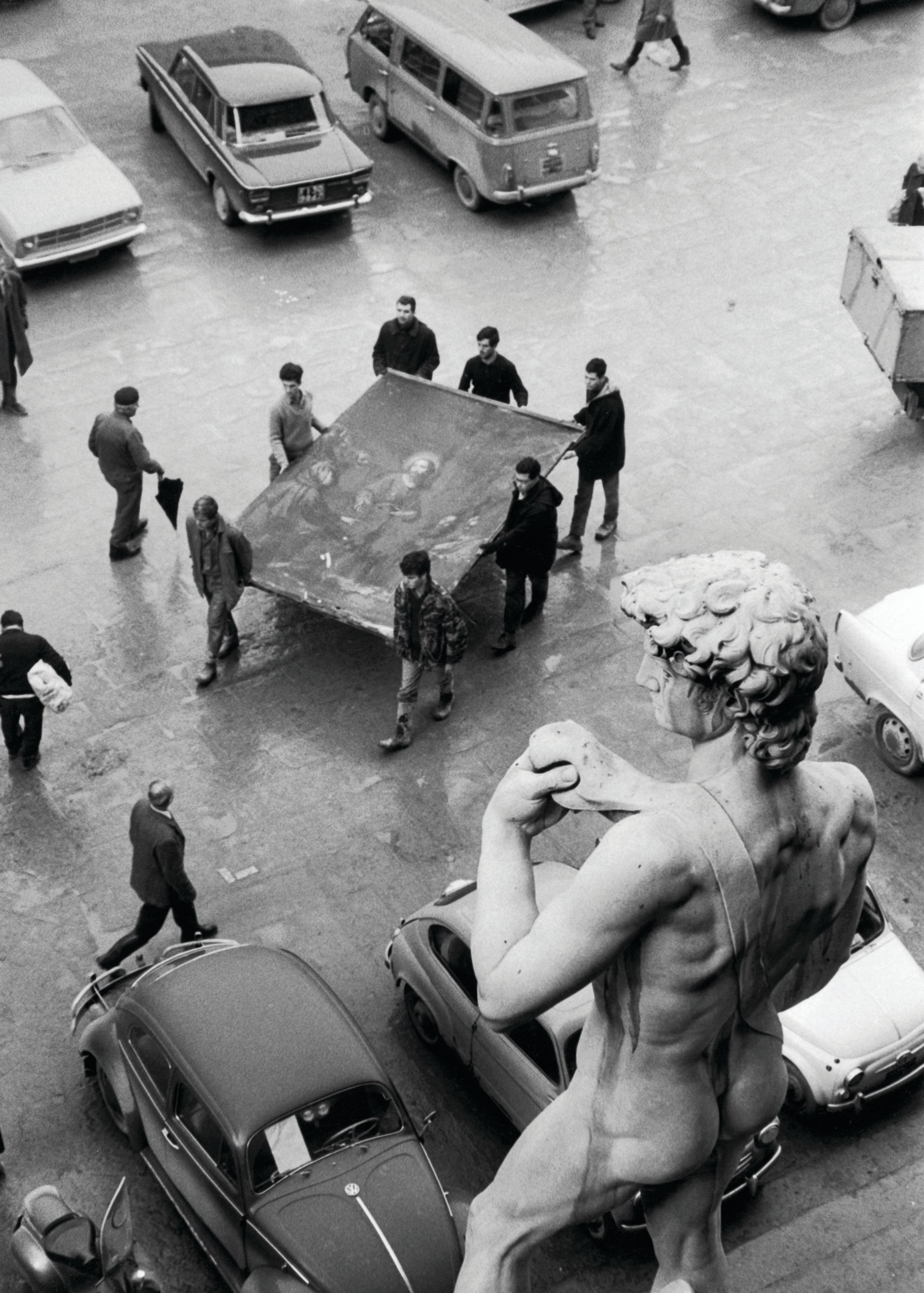

Within a matter of hours on 4 November 1966, more than 30 people had been killed in Florence, and the city’s rich artistic heritage had taken a seemingly insurmountable beating. The cultural disaster toll included damage to 120 frescoes, 300 panel paintings, 500 sculptures, 800 paintings on canvas, 6,000 volumes from the archive of the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore and 1.3 million rare books from the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze. Images of the destruction galvanised people from all over the world into action. Italian and foreign volunteers, known as mud angels, worked tirelessly, in often forbidding conditions, alongside Italian professionals to salvage the city’s art treasures. For the past 41 years, the Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation (FAIC) has collected the stories of these first responders as part of its ongoing oral history project, which documents the history of the conservation of cultural property. While the 320 interviews conducted so far cover all areas related to the field, around 10% of them provide new or significant information related to the Florence flood.

It is because of the FAIC initiative that we know that Ugo Procacci, the superintendent of Florence’s museums, cried when he saw the state of Cimabue’s 13th-century Crucifix (widely considered the Medieval artist’s greatest work)—half of its paint had been stripped away by the waters, which crested at Christ’s halo. It is also how we know that one panel painting still bears the imprint of the shoe of a museum guard because he did not realise what he was stepping on when he went to retrieve his raincoat, and that a representative from DuPont drove all the way from Paris with large container of Elvacite (a synthetic resin) for the conservators to use. The oral histories also revealed that a technique devised to remove oil stains from the city’s many sculptures came from a discussion on the best methods for getting spaghetti bolognese stains off clothes.

Conservators’ Tales

A group of conservators, including “Monuments Man” George Stout—the epithet referring to his part in helping rescue art and architecture from destruction and looting during the Second World War—started the oral history project in 1975. “No one else was collecting the history of the care of art collections,” says Joyce Hill Stoner, a paintings conservator from the Winterthur/University of Delaware art conservation programme. “We initially looked at other oral history projects at places such as Columbia University and the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art and wondered if we should be sharing efforts. But they were more interested in photographers, museum directors and artists than conservators. We had to start our own project to ask the questions required for us to care for these works of art.”

Hill Stoner has co-ordinated the project since its inception and was picked for the job because “I was young, energetic and could get things done.” She stresses that while an abundance of technical information can be found in specialist journals, what the profession lacks is anecdotes and the project is working to correct that. She says that some still “pooh-pooh” oral history as a credible source of information because they think memories are not trustworthy, but points out that memories do not necessarily have to be true to be useful. “People may have different memories of events, but those memories are still valuable because it is how they chose to remember a particular event,” she says.

She cites the 19th-century American artist James McNeill Whistler as an example. “He lied all the time, even under oath,” she says. “He liked to tell everyone he was born in St Petersburg, when he was actually born in Massachusetts. This detail actually tells us a lot. It tells us he wanted people to believe he was from Russia.” For Hill Stoner, “oral history is not straightforward, factual history, and should always be looked at in combination with other sources”.

The conservator Rebecca Rushfield, who works on the project, says it is not the individual interview that is important but the accumulation of them. “The value is in the quality and quantity, she says. “If six people say the same thing, there must be value in that.”

Soundbite-averse

Hill Stoner had to persuade some conservators to participate in the project and interviews can be embargoed for 50 years by request. “Conservators by and large do not work in the public eye and unlike artists are rarely interviewed because they don’t speak in soundbites,” she says. “I often have conservators who say, ‘Why interview me? I’m just in the service of the artist.’ I explain that they could talk about their mentors so the emphasis is no longer on them.”

The interviews related to the Florence flood, excerpts of which we are publishing below, reveal that it brought people around the world together during a difficult time, both politically and economically. “Europe was just beginning to recover from the Second World War,” Rushfield says. “This disaster enabled people to transcend differences.” Hill Stoner says: “The response was amazing because the entire world paid attention. But what can you expect when you see a Cimabue floating down the Arno River?”

In their own words: six 'mud angels' tell their stories Crisis meeting

“There was a general meeting of all the people at the Uffizi, headed up by [Umberto] Baldini, on the second or third day. The idea was to discuss the issue of what to do as an emergency measure. Several things became obvious immediately. The canvases posed rather less of a problem, but the panels required immediate attention. It was clear that the wood and all of the painting materials had swelled considerably—sometimes unequally, where only part of the painting was under water. But no one could stand up and say, ‘Yes, I’ve had a Florentine trecento triptych under water for two hours—I know what to do.’”

-Marco Grassi, New York-based painting conservator with a private practice in Switzerland and Florence in 1966

Mud, mud and more mud

“It was one continuous disturbing moment after another. One would try to walk around the streets, but with all the mud and stench it wasn’t easy. I remember walking down Borgo San Jacopo right by the Ponte Vecchio in rubber boots and stepping into one of the many open manholes because one couldn’t see them when they were filled with mud. The water pressure had pushed them open. I was in shock and I was covered with mud. It was pretty scary. We were told to carry a bottle of hydrogen peroxide around to disinfect ourselves if we got a scratch because the mud was so polluted.”

-Andrea Rothe, former head of painting conservation at the Getty Conservation Institute, who was working in Florence in 1966

Pumping out the Uffizi

“I rang my brother-in-law whose family owned a gravel pit company with a lot of heavy machinery. He persuaded his father to lend him a Land Rover and a big industrial pump. I recruited a bunch of students and we travelled to Florence non-stop, arguing our way through the cordon. Fortunately, we had a four-wheel drive vehicle—only this type of vehicle could possibly have got through. The mud was indescribable. The cold was appalling—it went right through our bones. The damp and the stink is something that lives with me to this day—the smell of dead cats, rotting flesh, decomposing material and sewage all over the place. Fuel oil was spread all around the city. We drove up in front of the Uffizi and asked what we could do. They looked at us with horror because it was less than a week after the flood. I looked around the Uffizi’s basement with all the blackened boxes… the place was absolutely awash with water. I queried why it had not been pumped out and was told they didn’t have any pumps. I said ‘I’ve got a pump!’ So the first thing we did was to pump out the Uffizi’s basement.”

-Patrick Matthiesen, London gallery owner and mud angel, who was a student at the Courtauld Institute of Art in 1966

Books triage

“[The books] were sent up to Fort Belvedere, where a sort of triage took place using symbols. We had various symbols that we devised mainly to overcome the language problems. The books were sorted when they came in and then shelved. We in turn went through them to see what could be processed first.”

-Anthony Cains had a bookbinding shop in the UK during the flood

A witness to human tragedy

“I bought my parents a set of lithographs as a thank you [for sending me to Florence]. One of them shows the mud. They’re in sepia and there is one of an older woman that I will never forget. She became a symbol [of the flood]. She was a larger, wheelchair-bound woman who lived in a ground-floor flat. Somehow she was able to hold onto the bars on the windows. They tried to go down to get her but they couldn’t get her out and she drowned in front of all these people. So she is one of the things that really struck me because she just couldn’t get out. That particular lithograph—and anyone who knows the series will know it—that’s the one that really knocks you over; it’s the one that really relates to human tragedy.”

-Anne-Imelda Radice, the director of New York’s American Folk Art Museum and a mud angel

Rising above politics

“While we were in Florence in the autumn of 1968, the Velvet Revolution took place in Prague [the Prague Spring]. Suddenly Soviet and Iron Curtain forces rolled into Prague. The Czech group and the Polish group [working in the Fortezza da Basso] therefore became official ‘enemies’. So they took a day off and got drunk—together. That was really something.”

-Erling Skaug, professor and senior fellow at the University of Oslo, who was an intern at the Istituto Centrale per il Restauro in Rome during the flood

Assembly line

“I was a nobody, but I watched [and] I did everything I was asked to do. They had to get me a pair of boots because I had brought trainers or something like that. Eventually they had this assembly line for putting interleaving [paper used for protecting works on paper] in. I managed to do a little of that… I never conceptualised myself as one of the great people who came to save things. I was not part of anything organised. And I knew there were students there who must have been conservation students and I wasn’t. I was just a schlepper.”

-Anne-Imelda Radice

• Most of the interviews were conducted in 2006