Today (19 July)—471 years to the day when the Mary Rose sank with 500 crew on board—the barriers erected during the vessel’s conservation to separate the ship from the public will come down.That people can actually visit the Mary Rose—Henry VIII’s prized warship sunk by the French, just 2km from Portsmouth Harbour, during the Battle of the Solent in 1545—along with its amazingly well-preserved contents is quite extraordinary.

The mere suggestion today of asking divers to tunnel under the wreck so it could be raised, as was done in 1982, would rightfully send health and safety advisers into a tizzy—not to mention the technical difficulties that come with building a museum around the wreck (which is around 35m long), on a Grade I-listed dock, while the vessel is being painstakingly conserved. Add in launching a campaign during a recession to pay for the construction of a museum to replace the 30-year-old “temporary” one and you have a recipe for disaster.

Despite these obstacles, the new Mary Rose Museum opened to much acclaim in 2013 at Portsmouth Historic Dockyard, securing a spot as one of the six finalists for the UK’s Art Fund Prize for Museum of the Year in 2014.

“Biggest showcase in the world” Visitors will be able to share the same space as the Tudor flagship that carried the king across the Channel to the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520 for his decisive meeting with Francis I of France. Floor-to-ceiling glass-fronted galleries filled with artefacts retrieved from the ocean floor encircle the lower and main decks to create what the museum’s deputy chief executive Robert Lapraik fondly calls “the biggest showcase in the world”. An open-air walkway, accessed by a door with an air lock, runs along the upper deck offering an unobstructed view of the Mary Rose and allows visitors to be in the same room as Henry VIII’s favourite ship.

In April 2013, a month before the new museum opened, the Mary Rose began its final major phase of conservation, in which 100 tonnes of water was extracted from its timbers through a process of controlled air-drying. In the 31 years prior, the ship’s hull was sprayed continuously with fresh water and then with the water-soluble wax, polyethylene glycol (or peg) to inhibit bacteria growth and to prevent the wood from drying out and cracking. According to Eleanor Schofield, the museum’s head of conservation and collections care, the ship was sprayed with two types of peg: one that penetrates the wood’s cellular structure, filling the areas that once held water, and another designed to seal the surface of the wood to give it greater strength.

Lessons of the Vasa Schofield acknowledges that peg does have its issues, most notable being that it appears to break down over time, as those studying the 17th-century Swedish warship Vasa have discovered. “It’s the least invasive treatment available today and you do the best with what you have,” she says, noting that keeping the Mary Rose in a stable environment will slow the rate of acid development. She is studying the breakdown of peg with scientists at the Vasa Museum in Stockholm.

The main part of the museum closed in late November 2015 so that crews could begin to remove the drying equipment, including hundreds of metres of ducting that snaked its way over and through the four decks of the ship. For Schofield, ensuring that the temperature and relative humidity levels remained consistent when the equipment was removed was a major challenge, matched only by taking apart and removing the temporary structure above the ship without damaging the hull. She also worked on engaging the contractors so that they understood the historical importance of the Mary Rose. The ship’s movement is monitored by lasers, which take measurements from several points every eight hours. And, yes, it does move, slightly, but Schofield says this is “normal”.

With this major phase of conservation completed, staff will both reflect on what could have been done differently and think about future plans. Around 19,000 artefacts were retrieved from the seabed, including 4,500 timbers that have yet to be conserved. “We need to categorise pieces as those to be conserved and those that we have a duty of care to look after and leave as is,” says Helen Bonser-Wilton, the chief executive of the Mary Rose. As Schofield notes, “Conservation is expensive, uses staff resources and takes a long time. The anchors alone take around 15 years.”

The museum has welcomed around one million visitors since its reopening in 2013. Bonser-Wilton expects around 400,000 annual visitors in future as long “as we keep it fresh” and “improve the offer”. The total cost to get the museum to its current state is £39m; the lion’s share of funding came from the Heritage Lottery Fund, leaving the Mary Rose Trust to raise £15m. “Every stage of this project has been a triumph of human endeavour,” Bonser-Wilton says.

Sank with the ship Only 35 of the ship’s 500-member crew survived the sinking of the Mary Rose on 19 July 1545. To get an idea of the scale of the disaster, the population of Portsmouth at the time was just 5,000. The starboard side of the ship and its contents lay perfectly preserved under a protective layer of silt for four centuries. “It’s our Pompeii; it’s everything perfectly preserved as it was on the day the Mary Rose sank,” says the museum’s deputy chief executive Robert Lapraik. Here is a selection of artefacts retrieved from the seabed.

• Hatch, the carpenter’s dog, has long been a favourite of visitors to the museum. Recent DNA tests have shown that this loveable mutt, a male, is a cross between a terrier and whippet.

• The Mary Rose Museum boasts the world’s largest datable collection of Tudor pewter, says the museum’s head of development, Sally Tyrrell. It includes serving platters, dishes, spoons and flasks, many of which have maker’s marks and initials of their original owners.

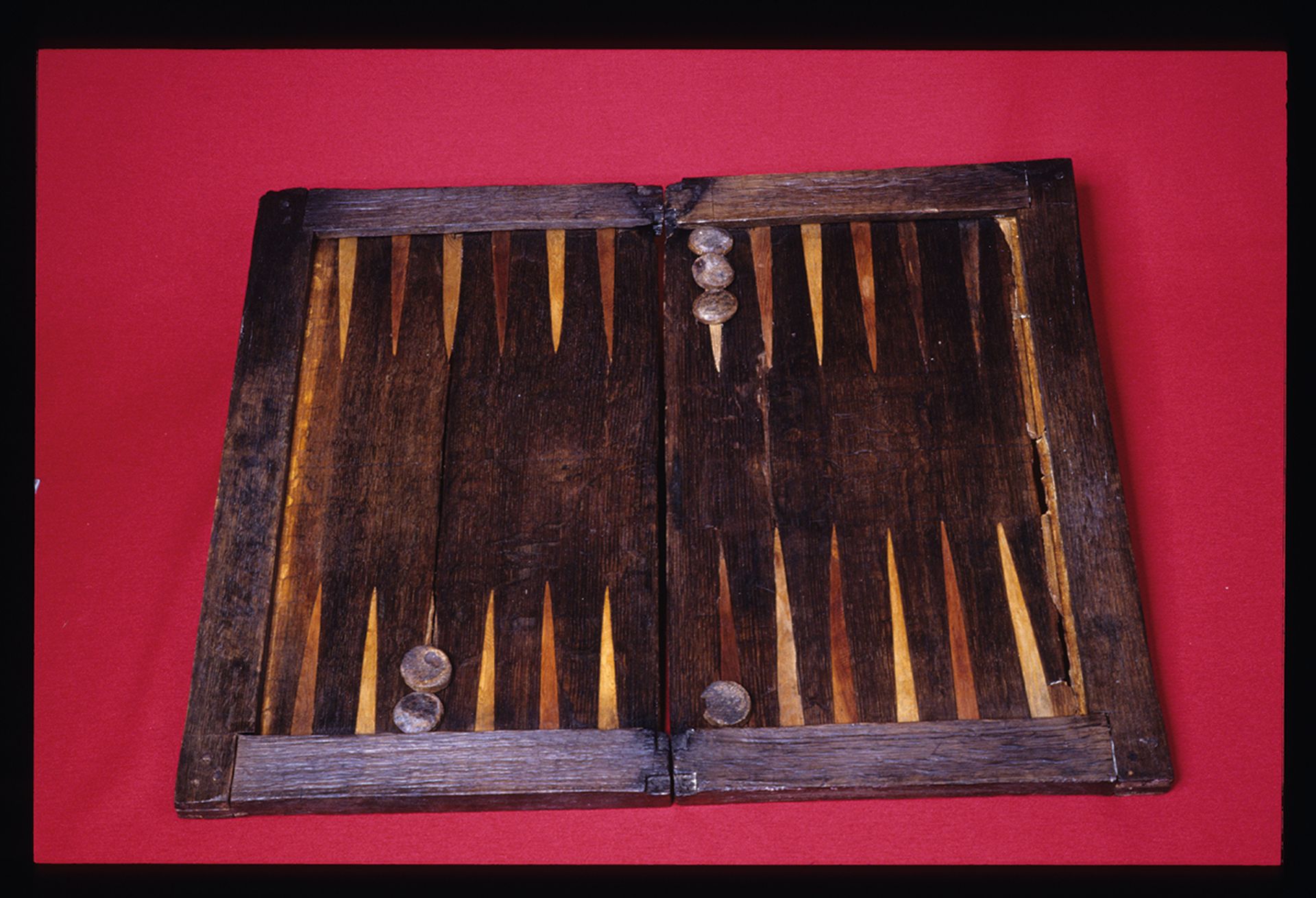

• Like Hatch, this wooden backgammon set belonged to the ship’s master carpenter. Dice made of bone were also found among the crew’s personal effects, offering an insight as to how the crew passed time onboard.