During his lifetime, the Early Netherlandish painter Hieronymus Bosch (around 1450-1516) enjoyed great wealth and respect, and his work was held in the utmost regard. His compositions, packed with pictorial innovations of an often grotesque nature, both surprised and delighted his audience, who were more accustomed to the idealised portrayal of nature found in 15th-century Flemish paintings and 16th-century Renaissance works. Within a decade of his death, artists were churning out hundreds of copies of his paintings and drawings, as well as new works inspired by his compositions.

Bosch’s fame continued to grow, peaking in around 1600, but over time, he was all but forgotten as the classical academic style, which relied heavily on idealisation, left little room for the grotesque. However, in the 20th century, scholars began to offer new theories of both Bosch’s best-known painting, The Garden of Earthly Delights (1503), and of the painter himself.

Art historians labelled Bosch an avant-garde, a sectarian, an alchemist and, according to Wilhelm Fraenger (1947) and Daniela Hammer-Tugendhat (1985), a pioneer of free love. In 1965, around 450 years after his death, the British psychologist R.E. Hemphill suggested that he had a schizoid personality disorder. He was, Hemphill noted, “withdrawn and inward-looking, unaware of the warmth of love”. This once celebrated artist had become an oddity.

Bosch was born in around 1450 in ’s-Hertogenbosch in the province of Brabant, in the southern part of the present-day Netherlands, far away from Bruges, Ghent and Brussels—the important centres of art and politics at the time. He was the third son of the mediocre painter Anthonius van Aken, who was himself the son of another mediocre painter, Jan van Aken, originally from Aachen, Germany. Bosch spent his youth training in the family workshop and, more importantly, attended the local Latin school run by the Church. It furnished him with only a basic foundation in religious studies, but it also taught him to be self-disciplined and to think cautiously and critically. Furthermore, it enabled him to mix with people from higher echelons of society.

Climbing the social ladder Bosch’s own social standing received a boost when he married Aleid van der Meervenne, the daughter of a wealthy tailor, in around 1480. Her inheritance, which included a house in the local market square as well as various countryside properties, enabled Bosch to set up his own workshop. In 1488, he became a member of the Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady (Illustre Lieve Vrouwe Broederschap), an exclusive religious confraternity made up of ’s-Hertogenbosch’s intellectual, clerical, financial and political elite. Although its fellows or “brothers” were required to take minor orders, and so were members of the clergy, they could marry and live outwardly secular lives while enjoying the benefits of being part of this influential social network.

Bosch painted two small panels and designed the stained glass for the confraternity’s chapel in the city’s main church of St John’s and received other crucial commissions from his confraternity peers, as well as their relatives. The brotherhood had connections throughout the Netherlands, including within various aristocratic courts, and Bosch soon gained commissions from outside his home town. For example, Peeter Scheyve, a high-ranking civil servant in Antwerp, commissioned him to paint the Adoration of the Magi (around 1496/97), which is now in the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid. By 1495, with his reputation on the rise, he had changed his name from Jheronimus van Aken to Hieronymus Bosch (the Latinised form of his first name, plus the short form of his home town).

Over the next few years, Bosch was to paint his large-scale triptychs—his most famous works. Arguably, the most popular of these is The Garden of Earthly Delights, now in the Prado. Although the precise details of its commission are unknown, scholars believe that it was painted to celebrate the marriage of Count Henry III of Nassau-Breda—one of the most important aristocrats in the Netherlands at the time—to Louise-Françoise of Savoy. It was intended to serve as a guide to making a successful marital alliance and as a warning about what could happen if the rules of faith and morality were not followed. It was also intended to entertain a courtly society.

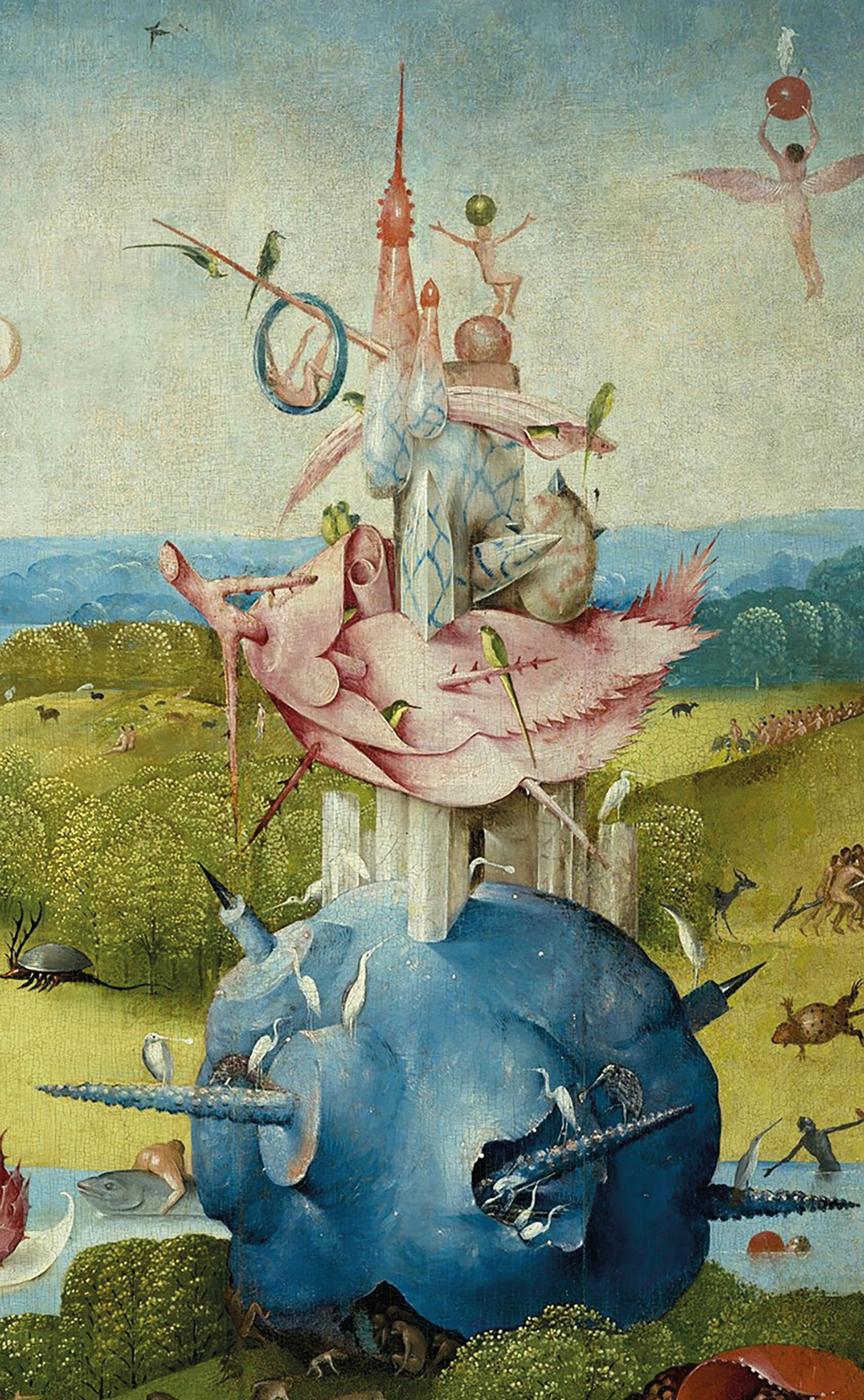

The triptych presents a succession of four related views. The creation of the world up to the third day decorates the triptych’s two exterior doors; Paradise and the presentation of Eve to Adam is on the left wing; the central panel depicts the false Paradise of humankind before the Flood; and the right wing features Bosch’s terrifying depiction of Hell.

Pleasing and fantastical The earliest recorded impressions of Bosch’s paintings come from Antonio de Beatis, the chaplain of Cardinal Luigi of Aragon, who saw The Garden of Earthly Delights during a visit to Henry III’s palace in Brussels in 1517—the year after Bosch’s death. He appears to have been pleased with the work, describing it as having “panels with fanciful themes… including people coming out of a seashell, others being excreted by cranes… birds and animals of all sorts and of great naturalness, the whole thing pleasing and fantastical”. Around 80 years later, José de Sigüenza, a librarian and confessor to King Philip II of Spain, wrote a moralising exegesis on The Garden of Earthly Delights. He interpreted the human figures, animals and plants in terms of the deadly sins and the transience and fleetingness of all earthly things. Although the interpretations of Beatis and Sigüenza may seem contradictory, they are, in fact, two sides of the same coin. They follow a maxim in Horace’s Ars Poetica: prodesse et delectare—or, to educate (in this case, to offer moral instruction) and entertain.

According to Sigüenza, Bosch knew that he had already been overtaken by Dürer, Michelangelo, Raphael and others. “Thus he embarked upon a new road, one on which he would leave the others behind.” Bosch created a new style influenced by the drolleries and grotesques found on Gothic buildings and in the margins of devotional books of hours. He took these creatures on the periphery and made them central characters within his panel paintings. He combined them with his observations of comical scenes from everyday life and images taken from Medieval proverbs, fables and myths—some of which did not have a pictorial tradition—to illustrate sins and follies.

The value Bosch placed on artistic innovation is scrawled at the top of his drawing The Trees Have Ears and The Field Has Eyes, in the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin: “For poor is the mind that always uses the ideas of others and invents none of its own.” This definition of what constitutes artistic talent testifies to a healthy self-respect. Bosch’s art lay in reimagining known themes by adding details with drolleries for emphasis.

He was a child of his time, the Renaissance, but had the verve to go his own way—not the way of harmony, idealism and illusionism, as in the art of Raphael and Dürer, but the way of allegory, riddle and disillusion, which enabled him to interpret religious art in a sovereign manner that had been impossible in the Middle Ages. Bosch’s images are not simple to understand. They can lack harmony and beauty, and any sensory enjoyment can be misleading. To understand his moralising pictures, viewers have to be able to clarify the relations within them and within themselves: how do I recognise what is good and therefore exemplary? What is evil, despicable and ridiculous? Only in this way can the viewer experience true beauty, by personally resolving these issues and undergoing spiritual reform—and becoming mentally and spiritually beautiful as a result. Despite all of Bosch’s artistic sophistication, his works are ultimately religious in intent.

• Stefan Fischer, Hieronymus Bosch: the Complete Works, Taschen, 300pp, £27.99/$39.99

1. The meeting of Adam and Eve

Christ in the act of presenting Eve to Adam is a rarely depicted Biblical scene. The moment between the creation of Eve and the joining of Adam and Eve in wedlock in the Garden of Eden alludes to the sacrament of marriage. Christ gives divine consent to the union—the ideal relationship between man and woman—by raising his right hand. Adam has awoken from his slumber and turns from inner contemplation of God to outer admiration of Eve in her pale and slender gracefulness.

2. Before the flood

Humankind before the Flood is depicted as a false Paradise. Hierarchy, harmony and the rightness of the Paradise on the left panel are converted—turned upside down like the men depicted standing on their heads. Furthermore, fish are flying, birds are swimming and fruit are so big they can take in or absorb men.

3. Towering folly

Some scholars argue that the central panel shows a Utopian society, but close inspection reveals a false Paradise. For example, the bountiful selection of giant fruit being eaten, pawed at and generally admired symbolises lust and adultery. The point is further made by the naked men and women overtly touching each other’s erogenous zones. Furthermore, the five towers that aspire to reach the heavens are built on shaky foundations. The moral here is that self-discipline and sophisticated delight have a higher currency than acting irresponsibly. The real joy in this painting is not what is depicted, but the way in which it is shown.

4. The tree-man

Bosch does not point his finger at the sinner. Instead, he shows the absurdity of sin through, for example, creatures such as the Tree-Man. The egg-shaped abdomen of a pale giant, who has dead tree stumps for legs and has stuffed his feet into rickety boat shoes, houses an “evil inn” (see below). The figure peers over his shoulder as he sticks out his buttocks—an all too clear symbol of the impurity of sin and the stench of hell. On his head, which is by far the grandest part of the body, he sports a disc that bears lustful sinners and a demon promenading around a bagpipe—a symbol of the male sex drive.

5. The evil inn

Hell is dominated by the theme of the “evil inn”. Often seen in literary references at the time, the term applied to brothels and shady taverns where patrons were exposed to any number of vices such as secular music, unlicensed gambling, unlimited amounts of alcohol and prostitution, any combination of which could lead to sinful behaviour. The evil inn was the antithesis of the Christian ideal, and as such, any believer would do their best to avoid this wicked place. It does, however, provide the painter with pictorial possibilities, namely the creativity to combine parts of things and living beings to show the hubris and the chaos of evil. For example, a demon with a bird’s head and butterfly wings, dressed as a knight, holds the ladder for two lost souls, one with an arrow painfully protruding from his buttocks, as they climb into the inn.

The Grand Tour: Go Bosch or Go Home Bosch fever is sweeping Europe, with an array of weird and wonderful events planned to mark the 500th anniversary of the artist’s death. Many celebrations will take place in his home town of Den Bosch (the colloquial name for ‘s-Hertogenbosch), where visitors can attend talks on everything from beer and monastic life to the history of psychiatry, board a Heaven and Hell cruise along the ancient waterways that snake around the city, take in the view from 25m up on top of the roof of St John’s Cathedral, watch a flotilla of out-of-this-world boats inspired by Bosch’s fantastical creatures and catch some of their favourite Bosch beasties take to the stage in the Dutch premiere of Hieronymus B. Below is a selection of this year’s must-see Bosch shows.

Jheronimus Bosch: Visions of Genius

Noordbrabants Museum, Den Bosch

Until 8 May

The festivities kicked off in earnest in February with the opening of a major retrospective in Den Bosch. The show, which includes 17 of Bosch's 24 surviving panels and triptychs, is the culmination of a nine-year research project into his body of work. Among the highlights is a late painting, the Haywain Triptych (around 1515), from Madrid’s Museo Nacional del Prado, which is making its first trip outside the Spanish capital in 450 years. Two other loans from the Prado were pulled at the eleventh hour after they were deattributed by Dutch researchers.

Bosch: the Centenary Exhibition

Museo del Prado, Madrid

31 May-11 September

A work not travelling to Holland for the retrospective is The Garden of Earthly Delights—the artist’s best-known painting and one of the Prado’s star attractions. It will, however, take pride of place in the museum’s own Bosch show. A number of the artist’s key works can be found in Spain, thanks to a historically strong interest shown by aristocratic Spanish collectors, including Philip II, who amassed a sizable collection of Bosch’s paintings. The Prado’s show will comprise around 60 works.

Nacho Carbonell

Stedelijk Museum, ’s-Hertogenbosch

18 June-11 September

Within two years of finishing his studies in industrial design, the Spaniard Nacho Carbonell had won two design prizes and had been nominated for the Design of the Year award by London’s Design Museum. He gained the nod for Lover’s Chair, which consists of two seats connected by a tunnel, enabling its occupants to engage in both public and private behaviour. This is the first Dutch retrospective for Carbonell, whose imaginative work straddles sculpture and design and shows a strong affinity for Bosch and Dalí.

Heaven & Hell (& Earth)

Stedelijk Museum, ’s-Hertogenbosch

24 September-15 January 2017

In a nod to The Garden of Earthly Delights, four contemporary artists will tackle the Boschian themes of Heaven, Hell and Earth in this circular “triptych”. A video by the Dutch artist Gabriel Lester, which is being filmed in India, will be flanked by the Swiss artist Pipilotti Rist’s video Homo sapiens sapiens (2005), which portrays Paradise before the fall of man, and Fucking Hell (2008)—a stomach-churning installation of nine glass vitrines filled with thousands of tiny figures who are committing or on the receiving end of various heinous acts—by the British artists Jake and Dinos Chapman.

• For more events and information, visit www.bosch500.nl