The Breuer building is back in business. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York opened the doors of the Met Breuer to eager press today, 1 March, ahead of its official public debut on 18 March. “We treated the building as a work of art in conservation,” the museum’s director Thomas Campbell said in his welcoming remarks. “We have cleaned the concrete…[and] scraped out chewing gum from the holes in the walls.”

The Brutalist building on Madison Avenue has been closed since the Whitney Museum of American Art moved out in November 2014. This month, it will become home base for the Met’s contemporary programme for at least eight years. The museum’s strategy is to put the art of today in historical context, where its holdings are much richer.

The Met is also eager to fill out its modern holdings and is cannily using the Breuer as a carrot for potential donors. Sheena Wagstaff, the museum’s chairman of Modern and contemporary art, announced a plan to present a rotating display of important gifts on the building’s fifth floor. The first exhibition will revisit the collector Heinz Berggruen’s 1984 gift of works by Paul Klee, which have not been shown together for more than 25 years.

The Met Breuer’s inaugural shows include the first US survey of the Indian artist Nasreen Mohamedi (until 5 June) and the sprawling thematic show Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible (until 4 September), which brings together incomplete work by artists from Titian to Twombly. “I can finally say I’ve been in an exhibition with Leonardo da Vinci,” the artist Kerry James Marshall said at the preview.

Unfinished offers a rare, sometimes revelatory, peek behind the curtain at how paintings are actually made. In some cases, the work’s incompleteness is a bit of a stretch—or even conceptually irrelevant. But the show represents a unique opportunity to trace common techniques across centuries of Western art. Here, we present five of the most interesting juxtapositions in the Met Breuer’s most highly anticipated exhibition.

Juan Gris, Woman Reading (around 1927)

Alice Neel, James Hunter Black Draftee (1965)

Both works were left incomplete by chance. Gris’s canvas is one of a group of paintings he left unfinished when he fell ill at the end of his life. Neel began working on this portrait of a young man just one week before he left to fight in the Vietnam War. When he did not return for a second sitting, she declared it complete.

Auguste Rodin, The Hand of Good (modelled around 1896-1902, carved around 1907)

Bruce Nauman, Untitled (Hand Circle) (1996)

The inspired pairing of sculptures by Nauman and Rodin is one of the exhibition’s most memorable moments. Nauman’s wreath of hands can be read as a mocking reference to the circle of life, while Rodin’s sculpture shows Adam and Eve emerging from God’s hand—which is itself emerging from an unformed block of marble.

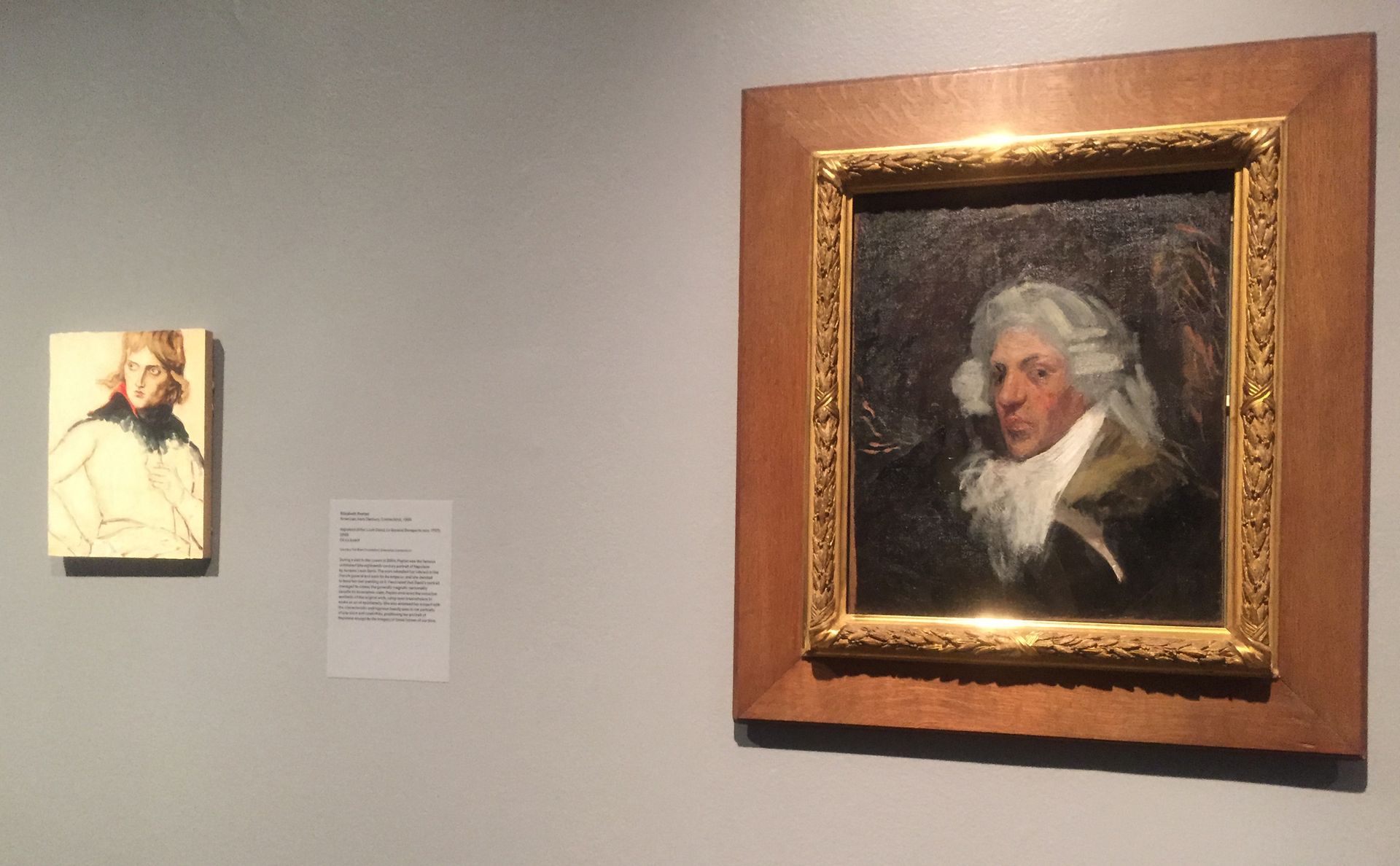

Pablo Picasso, Self-Portrait with Wig (around 1898-1900)

Elizabeth Peyton, Napoleon (After Louis David, Le General Bonaparte vers 1797) (2005)

Can the subject of an incomplete portrait still manage to look intimidating? Peyton’s petite portrait of Napoleon is modelled on David’s much larger, incomplete painting of the military leader on show at the Louvre in Paris. As a teenager in Spain, Picasso created this uncharacteristic portrait of himself inexplicably wearing a powdered wig. The dark background covers an earlier composition.

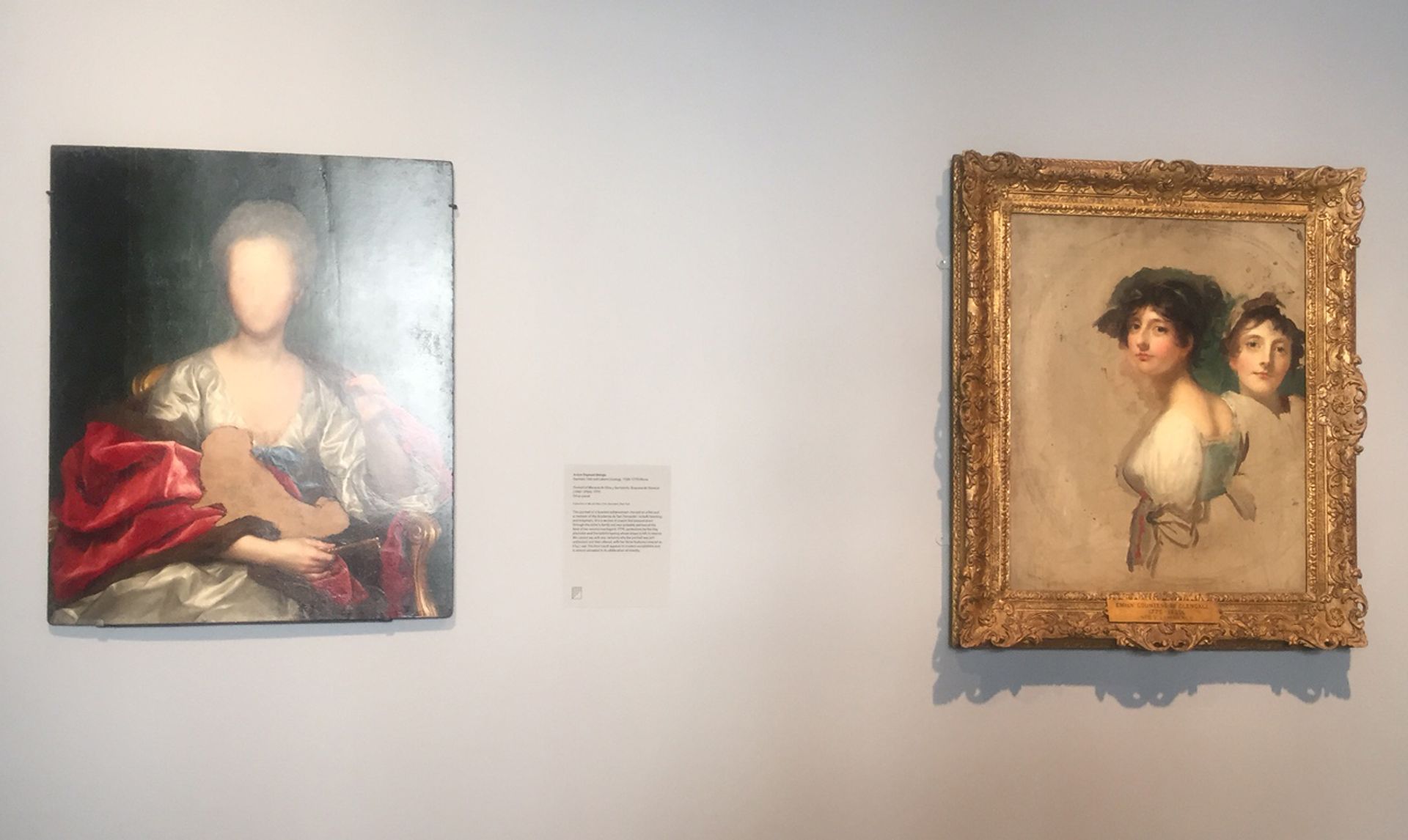

Anton Raphael Mengs, Portrait of Mariana de Silva y Sarmiento, Durquesa de Huscar (1740-1784) (1775)

Sir Thomas Lawrence, Emilia, Lady Cahir, Later Countess of Glengall (1776-1836) (around 1803-5)

These paintings were completed more than 200 years ago, but you might be able to convince your friends that they were painted yesterday. The portraits—commissioned by a Spanish and Irish noblewoman, respectively—offer a glimpse into how paintings spring to life and what artists choose to paint last. (Apologies to Mariana de Silva’s dog.)

Andy Warhol, Do It Yourself (Violin) (1962)

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (2009)

Both of these paintings leave parts unfinished, but offer a step-by-step guide to their completion. Warhol’s still life is one of five “do-it-yourself” paintings the artist created when paint-by-number kits became all the rage in the 1960s. Marshall, who will be the subject of a solo show at the Met Breuer this autumn, snuck a reference to paint-by-numbers into the painting within his painting.

• For a full review of the Met Breuer by Bruce Altshuler, the director of museum studies at New York University, see our April issue.