“I haven’t seen anything quite like it” is an oft-repeated phrase used to describe 500 Capp Street—the San Francisco home of the late US artist David Ireland (1930-2009). The 130-year-old building, which is considered to be the conceptual artist’s masterpiece, is a smart, two-storey Victorian house on a street mostly lined with new-builds. But within this unassuming structure lies a secret: its interior is filled with Ireland’s sentimental, playful and often mischievous site-specific installations, including a blowtorch chandelier and two bronze plaques nailed to the wall to mark the gashes made when his attempt to move a safe down the stairs didn’t go to plan. One simply reads: “The safe gets away for the first time, November 5, 1975.”

In 2008, when Ireland was frail and living in an assisted care facility, the house was at risk of being sold on the open market, where it would probably have been snapped up by developers and transformed into condominiums. Without knowing exactly what she would do with it, Carlie Wilmans, a local arts patron, bought the house. She has since created the 500 Capp Street Foundation to oversee the house’s restoration. She has also surrounded herself with Ireland’s friends, including the arts philanthropist Ann Hatch and the director of the Yale University Art Gallery, Jock Reynolds, to act as advisers. Ireland’s restored home is due to open to the public in January as the city’s newest arts space.

“Social sculpture” Wilmans was hooked after her first visit to the house. One work particularly struck her: Copper Window (around 1978). When one of the original windows broke, Ireland covered it with copper instead of replacing the glass. Before closing it off, he described the view, speaking into a tape recorder placed on a table beneath the window. “The San Francisco skyline has changed dramatically since the piece was made. It would have lost all context and meaning if it was removed and placed in a gallery. That’s when the wheels started turning in my head about how I could use my resources to preserve the house,” says Wilmans, who is the granddaughter of the late Bay Area arts patron Phyllis Wattis, who donated more than $150m to California’s cultural institutions. As well as leading the 500 Capp Street Foundation, Wilmans is also the head of a foundation named in honour of Wattis.

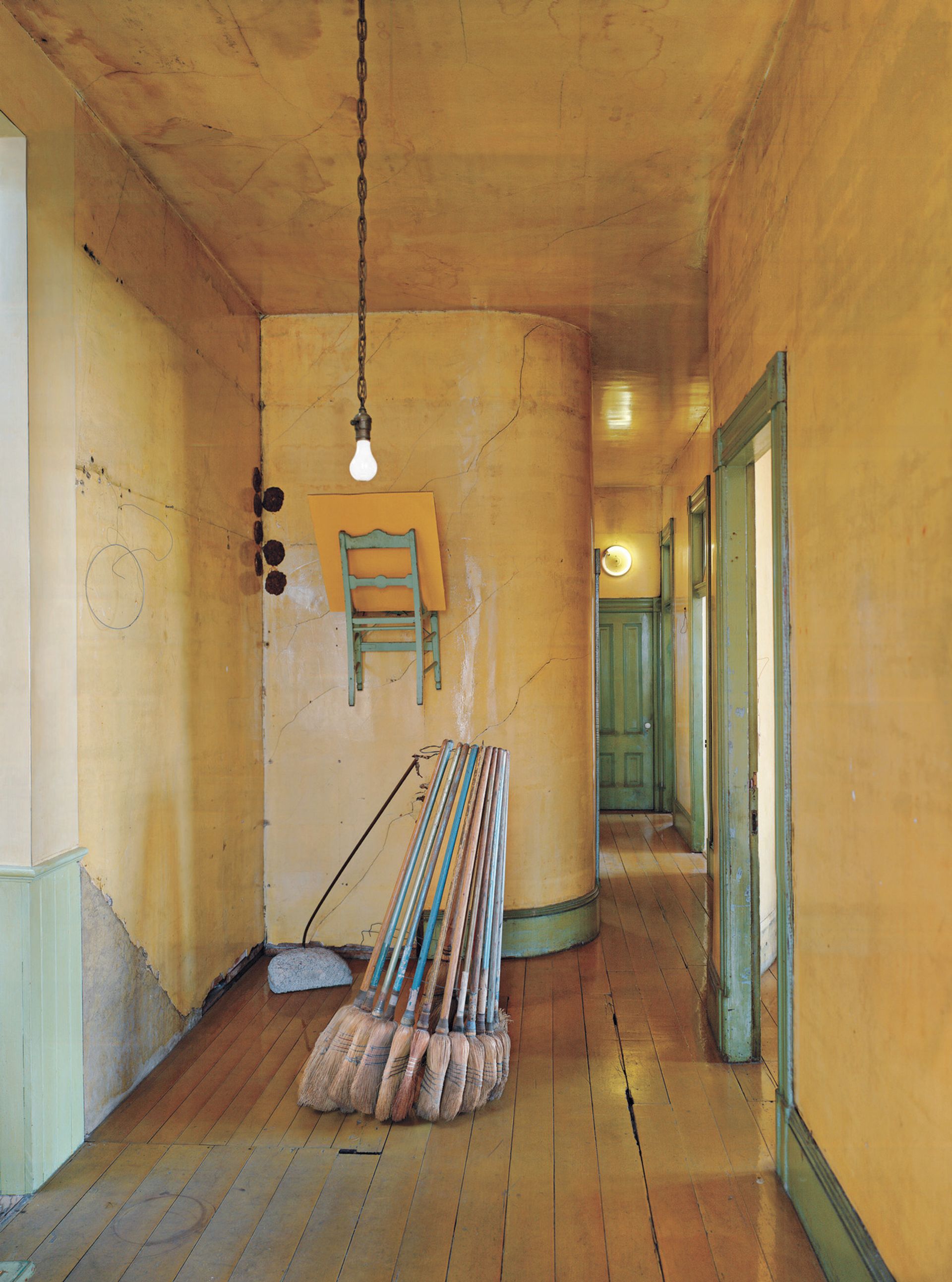

“As I toured the house, it became apparent how unique it truly is. It’s living sculpture, it’s social sculpture, it’s Ireland’s masterpiece. It would be a huge loss if it simply went away,” she says. Ireland saw the intrinsic beauty in everyday objects, and making art, usually from ordinary materials such as concrete, wire, bits of furniture and dirt, was part of his daily routine. Architectural projects—including his renovation, with the artist Mark Thompson, of the Headlands Center for the Arts in Sausalito, also in the Bay Area—earned him a following among architects, including Dean Orr of Jensen Architects, who was brought in to stabilise the house and create an addition. “His work straddles this line between art and architecture and links those two communities in a beautiful manner,” Orr says.

Wilmans knew of Ireland’s work only from that visit and from sitting on the acquisitions committee of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the institution owns several pieces by the artist. After taking the weekend to think it over, she decided to buy the property. She met Ireland half a dozen times before he died in May 2009.

Shaky foundation One of the first priorities was to stabilise the building, which had been undermined by Ireland’s digging in the quasi-basement to gather materials for his work and to create a space that he called his “inner sanctum, favourite studio and gold mine”. The Bay Area collector Steven Oliver, whose construction firm Oliver & Co served as the project’s general contractor, knew Ireland and was well aware of the house’s shaky foundation. He first met the artist in the late 1980s, when he was asked to look at it.

“He had dug a hole, ten feet deep, next to a stack of bricks holding up the floor,” Oliver recalls. “I said: ‘Hey, man, you have to stop. If this shakes, the whole house is going to get up in that hole.’” Oliver suspects that Ireland believed that he would be more forgiving because of his involvement in the arts. (Among other activities, Oliver and his wife Nancy founded the 100-acre Oliver Ranch in nearby Sonoma in 1985; it now has 18 site-specific installations by artists including Richard Serra, Bill Fontana and Martin Puryear.) “Fortunately, he stopped digging and we grew to become friends,” Oliver says.

Stabilising historic properties in earthquake-prone California is nothing new. But, for Orr, the technical challenge was not how to support a century-old home, but how to work on one with fragile interior finishes. Ireland had stripped the interior to its bare bones before covering the plaster walls and wood floors with a layer of transparent polyurethane. This coating not only provided a glossy sheen, it also celebrated the house’s age, laying bare every crack and imperfection.

“Normally, this kind of [stabilisation] work is done without regard to the occasional crack, plaster falling off the walls or floorboards coming up, as this can be repaired later,” Orr says. “But this wasn’t an option.” A light-handed approach was required throughout the project. “There was very little hammering, which is highly unusual in the construction business,” Oliver says. “Everything was done with screws as opposed to banging something.”

This isn’t Disneyland As well as technical challenges, Orr also faced conceptual ones—namely, the fear of “screwing up” a Bay Area icon. Besides creating a new foundation, the design included carving out an archive and study centre on the lower ground floor, and creating exhibition and flex spaces in an extension where the garage once stood. For the extension, the team used poured-in-place concrete, stainless steel and glass. The concrete is “a nod to Ireland and to the materiality of his work”, Orr says. Avoiding “some type of Disneyland-type fake historicism” was key to the design. “Conceptually, there was a desire to keep these two structures separate and, from a material standpoint, to look at a reductive palette to be sympathetic to David’s work, but also to provide a clean palette so as not to detract from the work inside the gallery spaces,” Orr says.

The conservators’ biggest challenge was dealing with the variety of finishes and materials used in Ireland’s work. “I’ve never seen anybody apply a polyurethane varnish to an entire interior before,” says Jennifer Correia from ARG Conservation Services. Ireland applied it in a very organic way, and the team used a light touch to ensure that brush strokes and drips were preserved.

After testing around eight coatings, they decided on an oil-based urethane varnish because it was the only one able to restore the high-gloss finish. Site-specific works that could not be removed during the construction work, including a series of mud and shredded wallpaper wall patties, were stabilised and covered with foam boxes. “We also kept the concrete torpedoes in place, as they were essentially glued to the ceiling,” Correia says.

Although Wilmans had advisers, the buck ultimately stops with her, so she agonised over certain decisions, including the addition of a lift. Orr questioned this decision several times, but “Carlie was adamant that it was an important part of the project for her”, he says. They eventually found a spot at the back of the house—one of the few spaces not touched by Ireland—to fit the lift. Wilmans says: “I was terrified that it was just something I wanted, but we unearthed some minutes with David’s attorney that show he wanted a lift, so that everyone could access the house’s upper levels.”

Wilmans wants 500 Capp Street to become the West Coast centre for the study of Ireland’s work. At the artist’s request, his papers were left to the Smithsonian in Washington, DC; Wilmans wants them to be digitised and made accessible in the house’s on-site archive. Ireland’s family donated his 3,000-strong art collection to the foundation and Wilmans has worked to get back some of the house’s key pieces that were sold off.

Getting the magic back Around four exhibitions a year will be hosted at 500 Capp Street, in the house and in the new extension, featuring works from the collection as well as pieces by artists responding to it. A roof-top terrace above the extension will serve as a space for film screenings, lectures and performances. An artist-in-residence programme open to artists of different disciplines is also in the works. “David collaborated with all types of artists—musicians, choreographers, writers, architects—so we want to honour that,” Wilmans says.

The soft opening took place in November, with Ireland’s friends being among the first to see the restored house when they came over for dinner and to trade stories. “He was known for putting on these wonderful dinners with an incredible mix of people,” Oliver says. “Some of the most magical conversations you could ever have in life took place around that table.”

Interior monologues: the art built into the house