In 1983, Christo and Jeanne-Claude surrounded 11 islands in Miami’s Biscayne Bay with 6.5 million square feet of floating fabric the colour of Pepto-Bismol. Next year, Christo will return to the water for his first public project since 2005. Floating Piers is also his first major work since the death of Jeanne-Claude, his wife and collaborator.

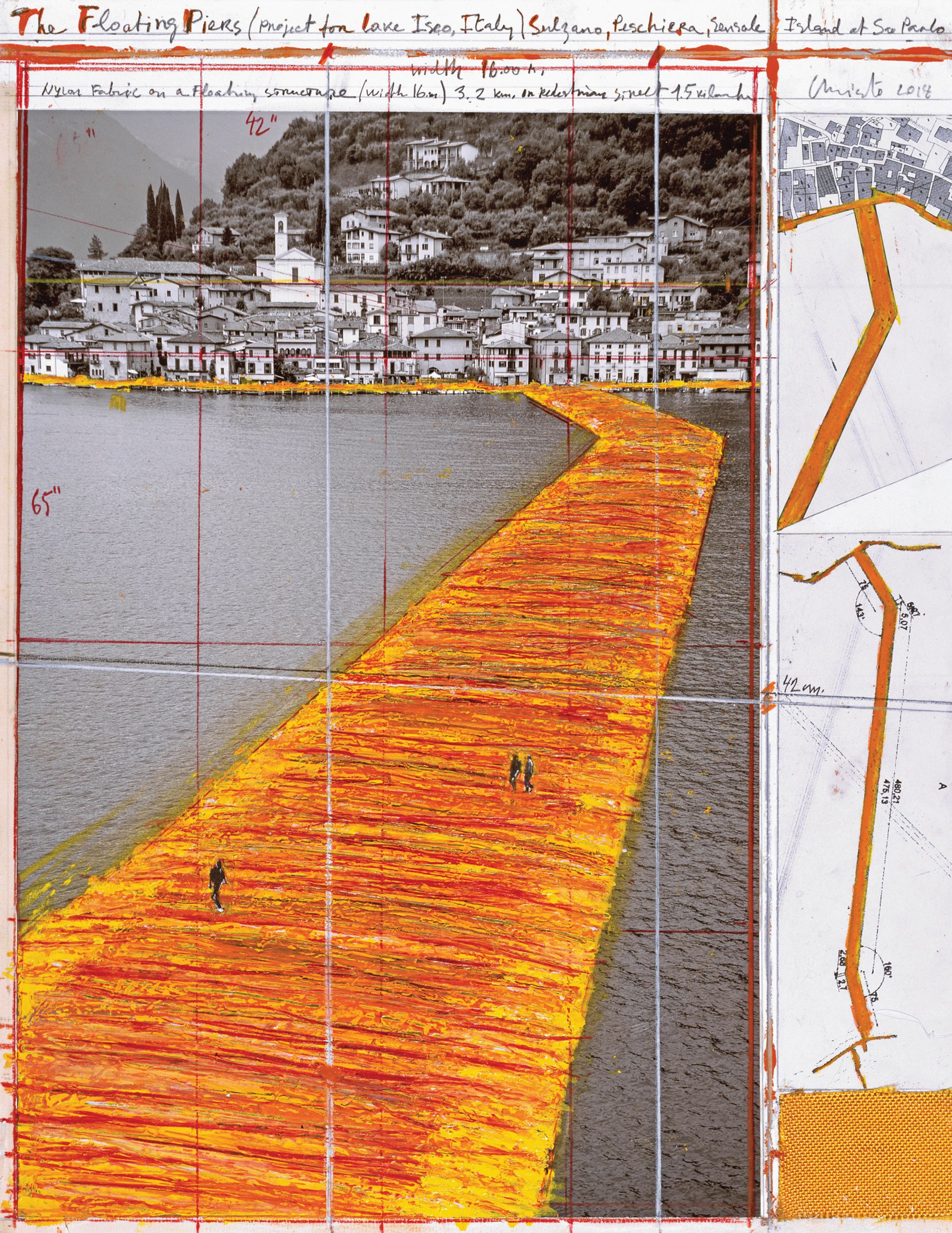

Christo and his team plan to erect a 3km-long walkway covered with 70,000 square metres of shimmering yellow fabric in the middle of Italy’s Lake Iseo. Visitors to Art Basel might want to plan a pilgrimage 260 miles south to the project (18 June-3 July 2016), which overlaps with the Swiss fair. The ambitious endeavour is estimated to cost around $11m, although the final budget has not been determined. Christo funds his projects through the sale of his drawings, preparatory sketches and other works of art.

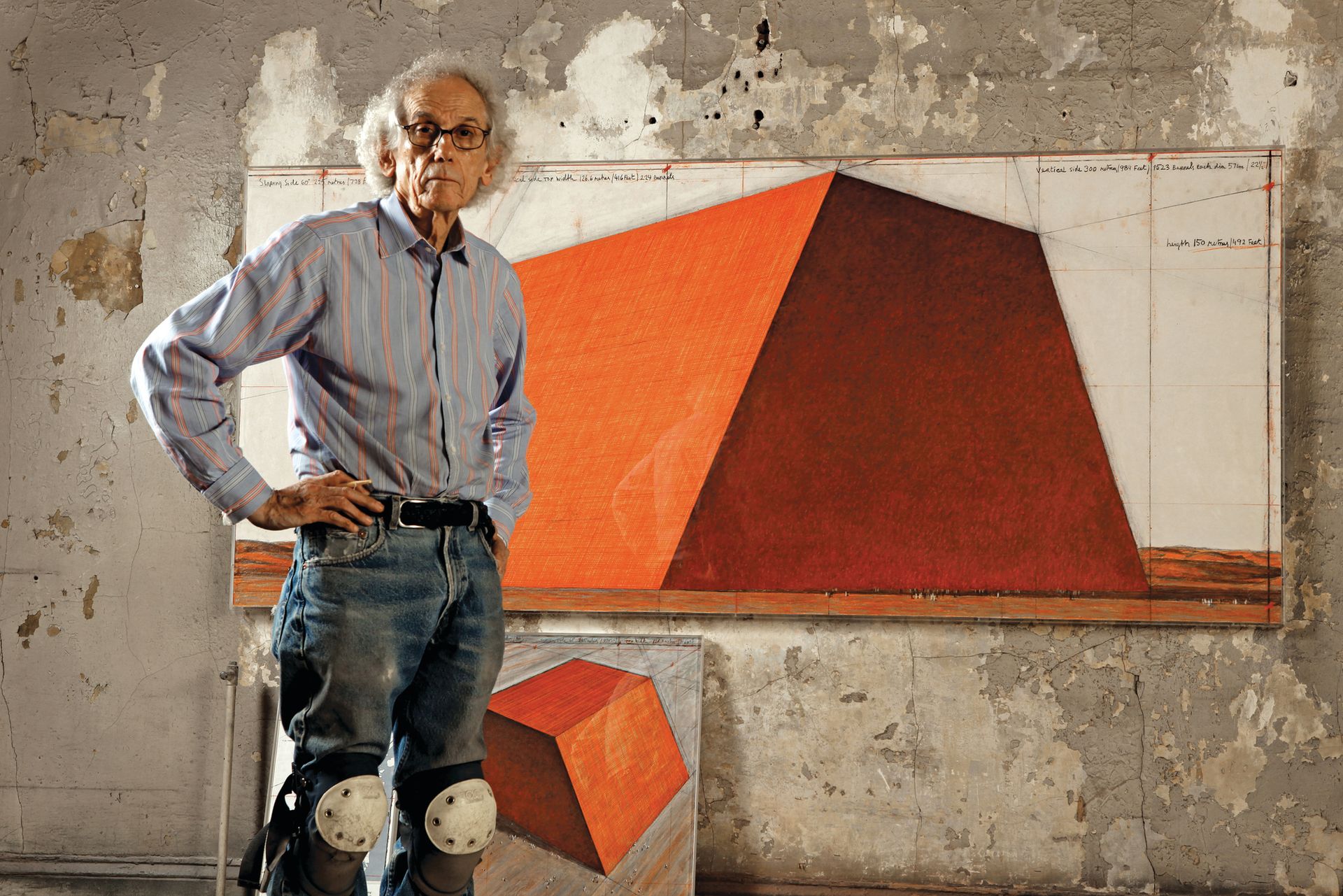

The Bulgarian-born, New York-based artist is 80 years old, and has never been busier. He was awarded the insignia of the Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters by the French embassy last month, and his work is the subject of three simultaneous exhibitions: at the Tampa Museum of Art in Florida (until 3 January), the Loveland Museum in Colorado (until 17 January) and Craig F. Starr Gallery in New York (until 23 January). We spoke to him at his studio in SoHo last month.

The Art Newspaper: Why did you want to make Floating Piers in Italy?

Christo: Some projects we design for a particular space, like The Gates in Central Park. For others, we have the idea and we have to find a site. In 1971, we proposed small floating piers in Rio de La Plata, near Buenos Aires. I did some drawings, but we never got permission. Then we tried to do it in Tokyo Bay. We worked on it for two years. The technology was not there, but it stayed in our hearts. Last year, I said: “I will be 80 and I would like to do something very fast.” So we decided to try again. We did three public projects in Italy in the late 1960s and early 1970s, so I thought it wouldn’t be too difficult, because they are familiar with my work.

Why did you choose Lake Iseo?

We visited four lakes at the foot of the Alps secretly; no one except our lawyers and some engineers knew that we were working on it. We chose Lake Iseo for simple reasons. It is accessible, 60 miles east of Milan, [and] one of Europe’s largest and tallest lake islands stands in the middle. Almost 2,000 people live on that mountain island. To go to the mainland, they take boats—there is no bridge. But for the first time, next year, they can walk on the water for 16 days.

Why did you want to enable people to walk on water?

The idea to walk on the water was very dear to us. I don’t sit in my studio—I am always standing. I have no chair, no stool. I don’t have an elevator. I climb around 90 steps, 15 or 20 times a day. You can find elements of water and earth in many of our projects. Running Fence [a veiled fence installed in the California hills in 1976] extended for a quarter of a mile into the Pacific Ocean. We installed Surrounded Islands in the Biscayne Bay. The beautiful thing with this project is that you will be walking on a pedestrian street and then, all of a sudden, you will realise that you are walking on water. A boat passes, and you feel it coming. It’s a very sensual project, very sexy. This project is so much about touch. I want people to walk bare-footed. Many people will [initially] feel imbalanced, because it’s not like you are walking on a bridge.

How did you execute the project?

In the late 1990s, there was an incredible invention: they figured out how to make piers and docks with high-density polyethylene cubes that float and are connected. In a special factory in Brescia, we are producing 200,000 cubes that will be connected by giant screws. To create the floating pier design, we are installing 140 anchors [that weigh] five to seven tonnes each. They will be placed inside industrial balloons, the kind used for oil exploration. Special boats will lead the balloons to the correct position, which is determined by the engineers. Then divers will open a valve, the balloon will deflate and the anchor will fall into place.

Your last major project was The Gates in Central Park, New York, in 2005. Since then, we have come to spend so much time documenting the world through our phones. Do you think that will change the way people experience your work?

I don’t stand for anything electronic. I don’t know how to drive. I don’t like to talk on the telephone and I don’t use a computer. I have no interest in virtual things. Our projects have the real things: the real wind, the real sun, the real fear, the real danger. Most art today is illustration. Galleries are full of illustration—art that illustrates war, that illustrates difficulty. But it’s not real. This is why it’s so banal, all this video. And on the sidewalk, you see people looking down at their phones. They are so outside of themselves that they forget the real fear of falling down and getting hurt. But you cannot replace the pleasure and the sensuality of real things.

Inside the mind of Christo and Jeanne-Claude: three unrealised projects For every project completed by Christo and Jeanne-Claude, at least one remains unrealised because the artists were unable to secure permission from the local authorities. “Over 50 years, we have realised 22 projects and we failed to get permission for 37,” Christo says. In many cases, they successfully executed a version of the same idea elsewh ere. But the original vision lives on in sketches. Here are three examples of what might have been.

Wrapped Trees, Paris (1969)

Maurice Papon, the prefect of Paris, rejected the artists’ bid to wrap 330 trees along the Avenue des Champs-Elysées and the Rond Point in Paris. (The city had already decided to decorate the trees with Christmas lights.) Twenty-eight years later, the artists successfully wrapped 178 trees with shimmering polyester and rope in Berower Park in Riechen, Switzerland.

Wrapped Walk Ways, Tokyo and Arnhem (1967)

After a trip to Asia in 1969, the artists sought to link Europe and Japan by simultaneously wrapping pathways in Ueno Park in Tokyo and Sonsbeek Park in Arnhem. But the local authorities would not cooperate. Unsuccessful efforts to wrap pathways in Ireland and Boston followed. Christo and Jeanne-Claude finally managed to install 135,000 square feet of saffron-coloured fabric along 2.7 miles of Jacob Loose Memorial Park in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1977.

Projects for the Museum of Modern Art, New York (1968)

Christo and Jeanne-Claude proposed a complete takeover of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). They wanted to wrap the building, fill the sculpture garden with a giant inflatable package and block the street in front of the museum with 441 oil barrels. But MoMA’s insurance company said it would cancel its coverage if the museum went through with the project.