Museums spending tens of millions of dollars building performance-ready spaces may find the running costs higher than expected as artists and activists look to raise and standardise pay for performers.

Tate Modern in London spent £90m in 2012 to transform a cavernous former oil tank into the first museum gallery dedicated permanently to performance. The new $422m home of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York includes the museum’s first dedicated theatre as well as gallery floors designed to cushion performers’ feet. And New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is dedicating a significant portion of its expansion to flexible spaces for live art.

Reality and retrenchment Museums may have to scale back their ambitions once they realise “how much it costs to run an active performing arts programme”, says Philip Bither, the senior curator of performing arts at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. This month, the Walker plans to host an invitational conference about the relationship between performers and museums. “I’ve talked to colleagues who are surprised when they mount live art in galleries that you have to pay people at all.”

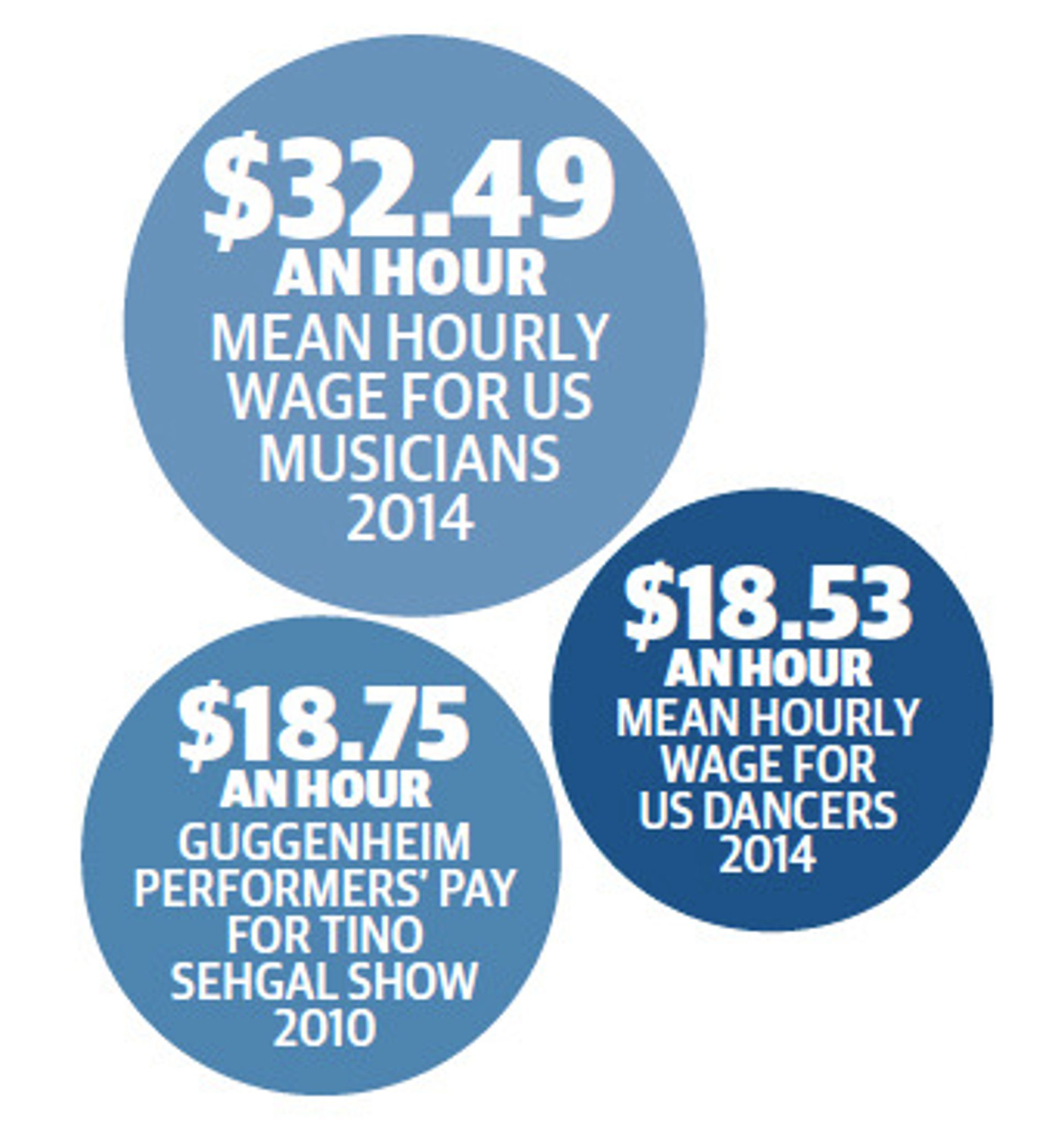

Unions help to set a baseline hourly wage for actors and musicians (classical musicians in New York make around $90 per hour). But few guidelines exist for the visual arts, and fees vary. Michael Clark’s Who’s Zoo? performance at the 2012 Whitney Biennial used professional dancers alongside unpaid volunteers. MoMA initially offered performers in Marina Abramovic’s 2010 retrospective $50 for a shift lasting two-and-a-half hours, but eventually agreed to pay around $95 per shift plus fees for waiting time, according to people involved in the negotiations.

“If you aren’t paying for objects, couriers and installation, you are paying for performers’ time,” says Nancy Spector, the deputy director of New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, which has acquired seven performances since 2010. “I would love to look more closely at the wages in theatre and dance if we are going to be consistently showing live art.”

Some artists are taking it upon themselves to work out guidelines. Brennan Gerard and Ryan Kelly worked with the Guggenheim and the public policy specialist Heather McGhee to develop employment standards for Timelining, which was acquired by the museum last year and is included in the show Storylines (until 9 September). The artists spent the past year drafting a 75-page instruction manual that they plan to use as a blueprint for every work they sell.

They specify that fees should reflect the living wage ($13.13 an hour in New York), a minimum determined by a city’s cost of living. (The Guggenheim volunteered to pay significantly more, Spector says.) Participants perform for no more than three hours, but must be paid for an eight-hour day to account for commuting and other opportunities given up to participate. They should also be hired as temporary employees so they are covered by the museum’s insurance in case of injury.

“We felt that the labour of the performers was inextricable from the aesthetic value of the work,” Kelly says. Although museums must be willing to pay up to comply with their guidelines, “the return is huge—these are experiences the public wants to have. I'm excited about the possibility that museums may become full of people who are making art live on site.”

$100 a day, minimum The activist organisation Working Artists and the Greater Economy (Wage) suggests that a fair fee for performers would be $20 an hour or $100 a day, whichever is higher, for organisations with annual operating expenses between $500,000 and $15m. Institutions with annual operating expenses of more than $15m should pay $200 a day, they say. Under these guidelines, we estimate it would cost more than $200,000 to present a large-scale work by Tino Sehgal for six weeks, as the Guggenheim did in 2010.

“Performers are beginning to set a minimum for what they are willing to work for,” says Abigail Levine, who performed in Abramovic's retrospective and Lygia Clark’s 2014 retrospective at MoMA. “It is a new, big pill for museums to swallow.”