Ibrahim El-Salahi was suffering from flu at home in Oxford, when he was wakened from the miasma of illness by startling images and descriptions of the Arab Spring on his television and radio. For the next six weeks, the 85-year-old Sudanese artist made drawings “triggered by what I was witnessing in the news,” he recalls. “[First] in Tunisia, where the Arab Spring started with the young man who burned himself to death in despair; then, as events unfolded in Egypt.”

The resulting series of 46 ink sketches, called The Arab Spring Notebook, is going on show in its entirety in Istanbul in September. The notebook was exhibited in a case in the artist’s retrospective at Tate Modern in 2013, but the drawings have been separated and framed for the Istanbul exhibition at Galerist’s project space (1 September-17 October). The show has been co-organised by London’s Vigo Gallery to coincide with the Istanbul Biennial (5 September-1 November). The series is available for the first time, for £90,000.

Nick Hackworth, the creative director of Galerist, says it can be problematic showing works on the Arab Spring in the Middle East. “Coinciding with the Istanbul Biennial is the best possible platform to present El-Salahi’s work to an engaged audience in the wider region,” he says.

Born in Omdurman in 1930, El-Salahi studied in Khartoum and London and travelled widely before returning to Sudan in 1957. He left in 1975 after being falsely accused of anti-governmental activities and imprisoned without trial. In prison, he conceived a nine-part painting, The Inevitable, and would sketch on the back of small cement casings, burying them in the sand whenever a guard approached. He eventually painted The Inevitable in 1984 and 1985, a decade after his release. It was a time of short-lived revolt in Sudan and the painting’s message was clear: people must rise up against tyranny and oppression.

At first, El-Salahi saw the Arab Spring as an expression of the same revolutionary power. “I thought it was a long time in coming, and a result of what I had expressed many years earlier in my work as The Inevitable,” he says.

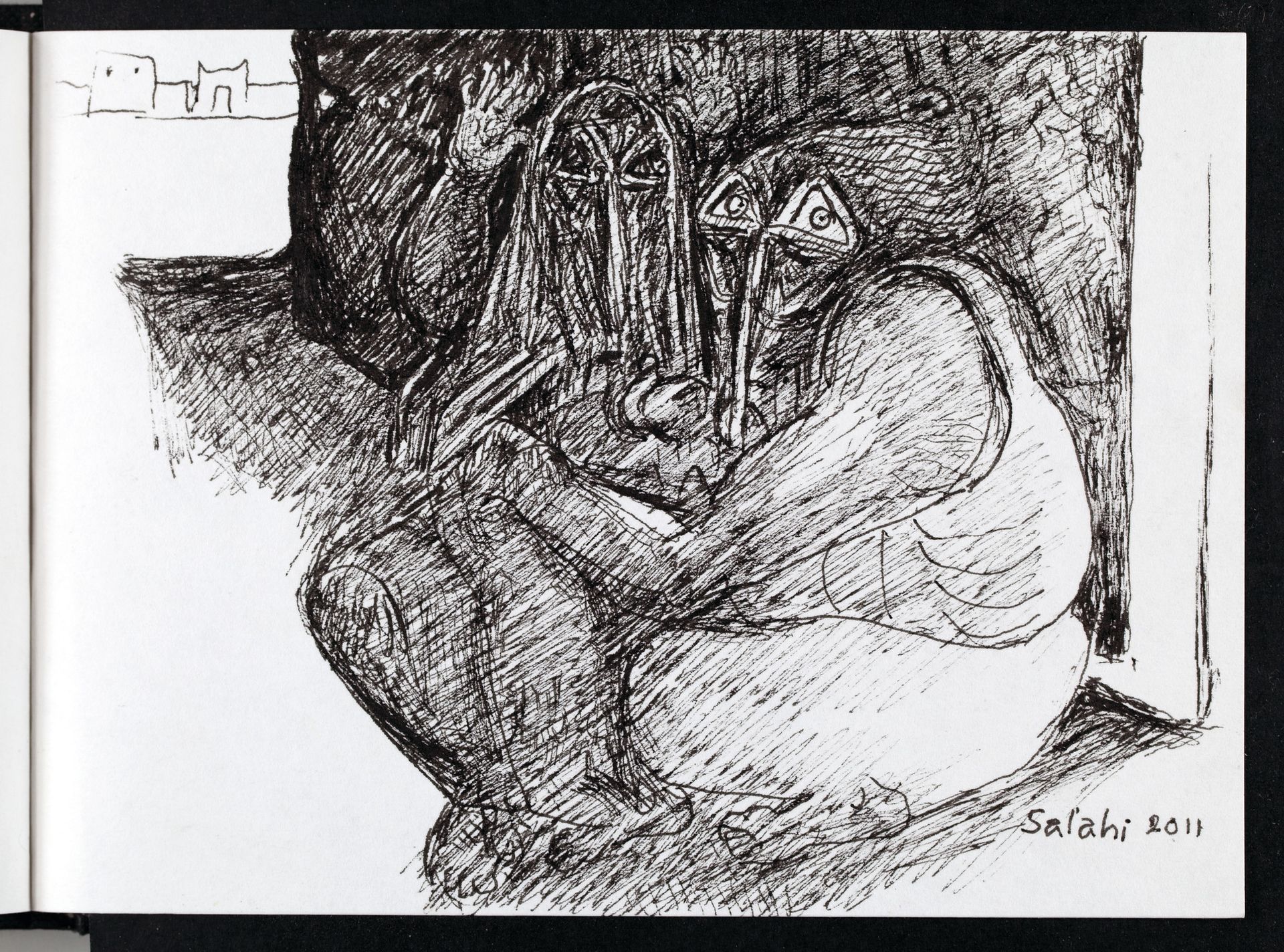

But, as the Arab Spring unfolded, revolution gave way to violence and El-Salahi’s sketches became darker: drawings like Repeating the whirlwind (2011) reflect a sense of foreboding. “In the beginning it was great to have a revolt against the tyranny, but [the series] shows mess upon mess [and a] complete lack of hope,” El-Salahi says.

Ultimately, the Arab Spring has brought about more repression than freedom, he argues. “See what happened and still is happening in Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Libya and Syria,” he says. “All led to the rise and spreading of a wave of destruction that will end in a heap of rubble.”

El-Salahi’s profile has grown in recent years, with the Tate, the Guggenheim and the Art Institute of Chicago, among many others, buying his work. Toby Clarke, the director of Vigo Gallery, says it is only now, at 85, that El-Salahi is releasing his works for sale. “He is known for not liking to part with his works, sometimes for decades,” Clarke says. “We have a few Turkish collectors, but no experience of exhibiting in Istanbul, so we are working with Galerist to introduce more local collectors to Ibrahim’s work.” Newcomers to El-Salahi’s art in the Turkish capital are promised a powerful and haunting initiation in The Arab Spring Notebook.