A delegation of art world, copyright and government experts from eight countries, plus European Union representatives, have called for an international review of royalty rights for artists following a conference at the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) in Geneva. The issue was officially added to the organisation’s agenda on 3 July—a significant first step towards negotiating a global treaty.

China, Iran, Sudan, Kenya and Tanzania, none of which currently has legislation, voiced support for the adoption of royalty rights. Senegal, Ivory Coast, Brazil and the EU, which have already passed legislation, backed a universal solution. The topic is due to be debated at the WIPO in December.

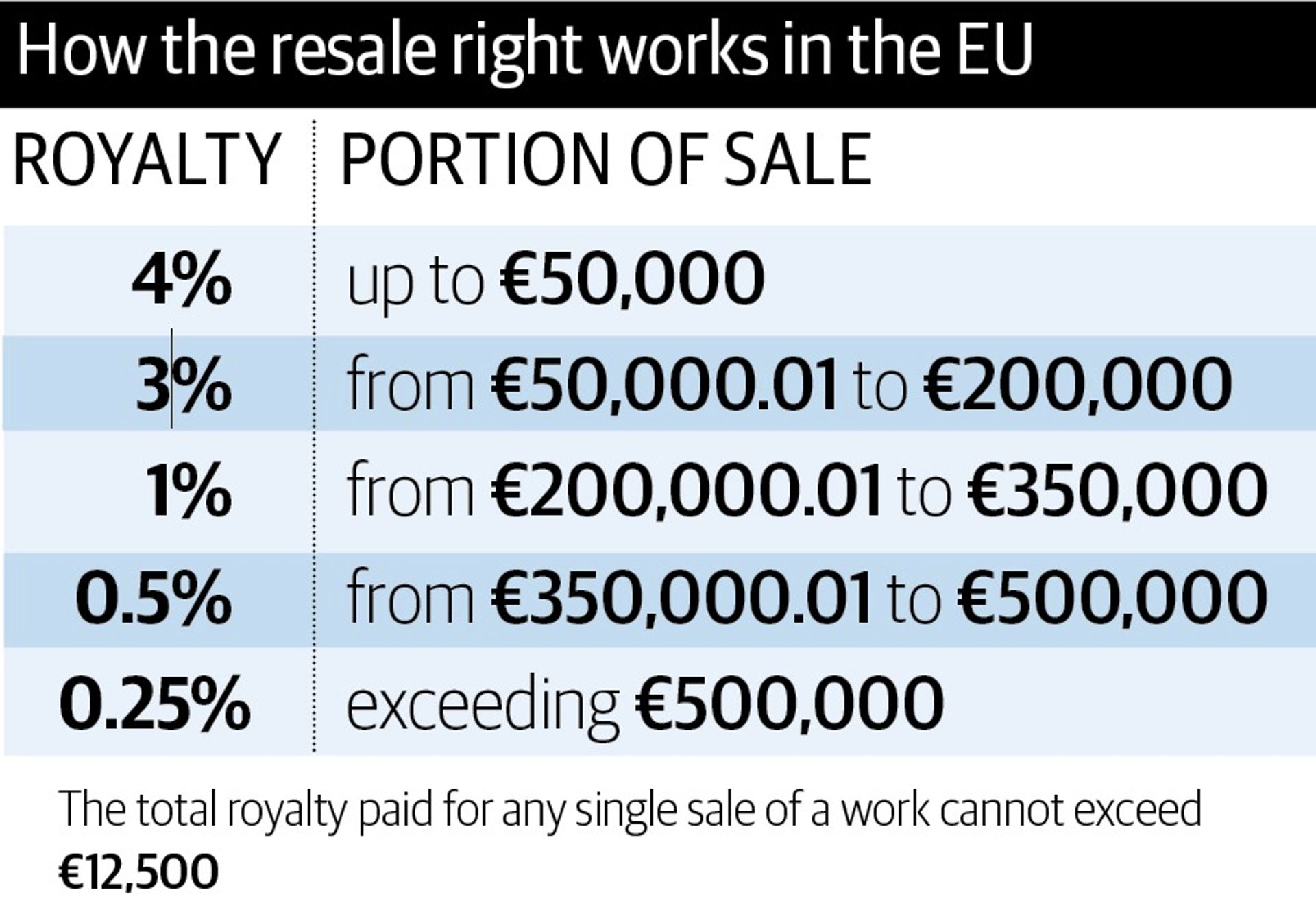

Today, 81 countries have some form of royalty rights that apply to secondary market sales of all works by living artists and those who have died within the past 70 years. Bills to introduce rights are either pending or being debated in the US, Canada, Switzerland, New Zealand and Argentina.

The main argument for a global treaty is that it would level the playing field, particularly in China and the US—the two largest art markets in the world. London-based Gordon Cheung is one of 50 artists supporting the DACS Foundation, a new visual arts charity affiliated to the organisation of the same name, which collects and distributes royalties in the UK. He says: “So many sales take place in countries that don’t recognise the right, such as the US or China. This unfairly disadvantages artists based in these countries, as well as artists whose work sells in these countries.”

The resale right is inscribed in the international Berne Convention. However, its implementation is optional. One solution would be to make it mandatory, says Professor Sam Ricketson of Melbourne Law School, who presented a study for a global treaty at the WIPO conference. Ricketson’s other proposals include an agreement to adopt and harmonise elements of national laws.

However, a report published last November by the British Art Market Federation (BAMF) blames royalties for contributing to a 3% decline in Britain’s share of the global art market in 2013. Anthony Browne, the chairman of BAMF, says royalties have minimal impact: “Last year, 2.6% of all artists and 1% of British artists whose work sold at auction in the UK benefited from royalties. Even then, the lion’s share usually goes to successful artists with developed resale markets.”

Critics of the BAMF report say its data is misleading as it is based on auction sales, so accounts for half of the market.

A DACS spokeswoman says that living artists received 57% of fees in 2014, compared with 43% going to artists’ estates. She adds that just over half of artists and estates paid in 2014 received less than £500, suggesting that the scheme “does not only benefit artists whose work sells for a lot of money”.

Many artists agree. Hervé Di Rosa, an artist and the vice-president of the Paris-based Société des Auteurs dans les Arts Graphiques et Plastiques, says royalties could offer an alternative income as public funding for the arts diminishes: “In ten years’ time we won’t have a culture ministry in France—or anywhere else. Private sponsors can pick and choose who they help. We need to find a new source of money for artists.”

Ricketson’s study, commissioned by the International Confederation of Societies of Authors and Composers, suggests there is still a long way to go—but royalties are nevertheless on the rise. In the UK in 2013, £8.4m was distributed to more than 1,400 artists and artists’ estates, almost doubling the previous year’s total of £4.7m.

But, for some, royalties simply mean more regulation, impeding free trade. “Once an artist sells something, it’s sold,” the London-based dealer and curator Kenny Schachter says. “Then they go back to the studio or fabricator and make some more. It’s a time-worn exchange that has lasted thousands of years and should remain in force simply as it is and always was.”

More harm than good?

In Australia, resale rights were adopted in 2010 primarily to benefit indigenous artists. But according to the Australian artist John R. Walker, royalties have been “highly corrosive” to the country’s art market. What is more, he says, the system favours white artists, with 60% of fees going to them. In 2010, in the tourist town of Broome, Western Australia, there were ten businesses trading in indigenous art; now there is one. Auction sales of indigenous art have plummeted 80% between 2007 and 2014, and the celebrated artist John Mawurndjul is retraining as a tyre repair man, according to an article by Walker published in August on the website www.art-antiques-design.com