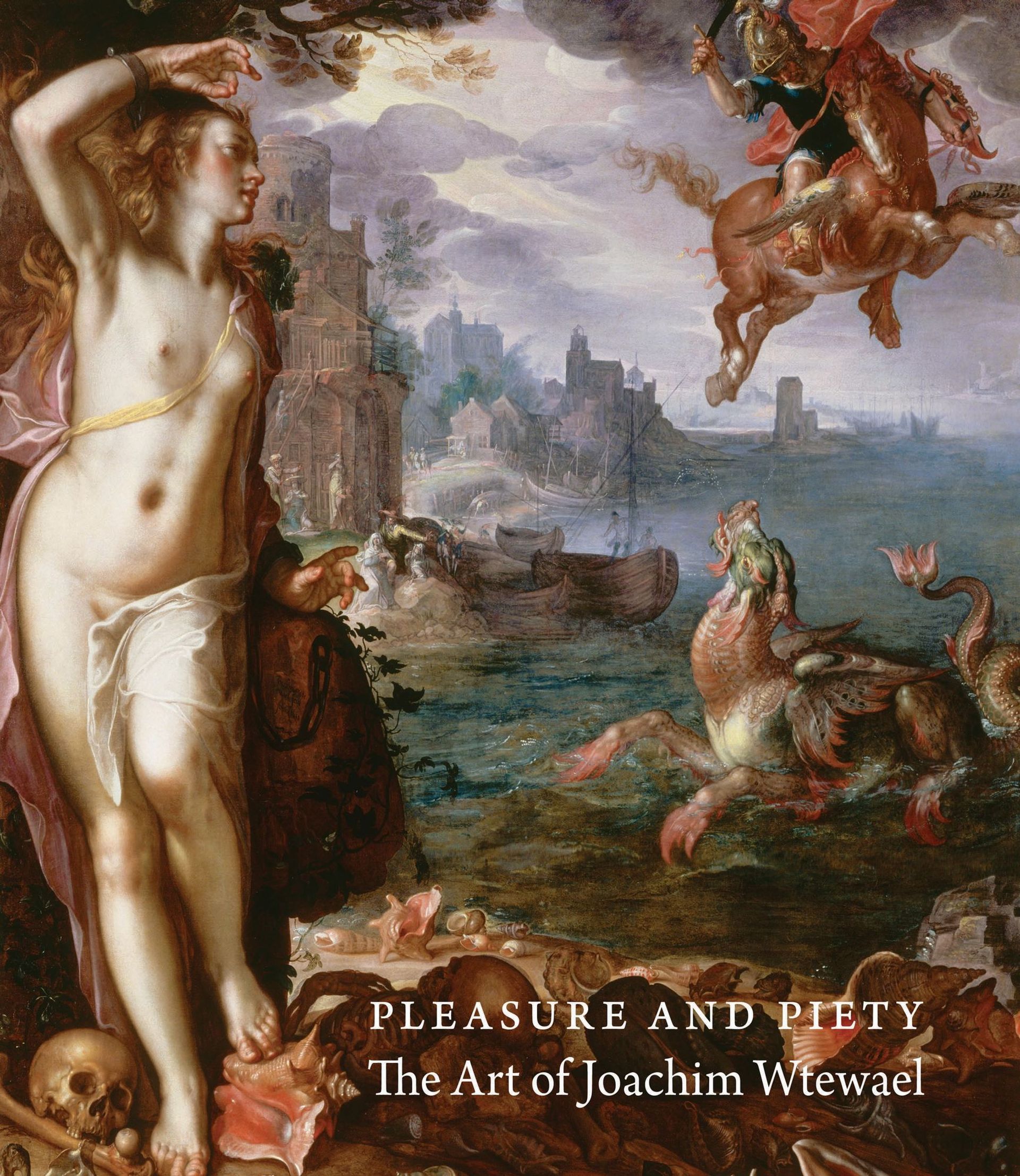

In 1604, Karel van Mander, the earliest Northern biographer of painters, hailed Utrecht-based Joachim Wtewael (1566-1638) as one of the best Netherlandish painters of all time. Van Mander must have admired Wtewael’s seductive and brilliantly coloured compositions, which usually narrated erotic mythological subjects but also extended to Biblical scenes, peopled with attenuated figures in elaborate, exaggerated and contorted poses that pushed the characteristic features of the International Mannerist style to new heights.

The biographer praised Wtewael’s ability to work on a small and on a large scale, a quality that he believed reflected the artist’s “good judgement and insight”. Van Mander was especially fond of the “excellent precision and neatness” of Wtewael’s small paintings on copper, which comprise one-third of the artist’s work. Unfortunately, the fame and positive reception enjoyed by Wtewael during his lifetime did not endure. He was out of favour for much of the 18th and 19th centuries, and his work did not begin to undergo a revival until the last quarter of the 20th century, when scholars reassessed the importance of Northern Mannerism in a series of important monographs and exhibitions.

Wtewael (pronounced OOO-te-vaal) is still not a household name. A native of Utrecht, he learned the lessons of Mannerism from his travels to Italy and France, and from prints by Hendrick Goltzius after designs by Bartholomeus Spranger, the foremost Mannerist artist at the Prague court of Rudolf II. Although Wtewael was a successful painter, he was not financially dependent on his art, since he also ran a successful flax business. This financial security probably accorded him greater artistic freedom.

The insightful new exhibition catalogue Pleasure and Piety: the Art of Joachim Wtewael, which accompanies the first, much-anticipated monographic exhibition on the artist (the show opened at the Centraal Museum, Utrecht, earlier this year), reaffirms Wtewael’s place among the finest Dutch masters. The richly illustrated volume explores, in a series of intelligently conceived essays, the artist’s highly refined paintings and drawings within the sociopolitical context in which he lived and worked.

It also provides a fascinating account of how Wtewael’s seductive art was, at times, censored, and explains the artist’s critical fortunes long after his death. The essay on Wtewael as a draughtsman is particularly welcome, because it is the first broader discussion of this subject since a 1929 German monograph in which 65 sheets were attributed to Wtewael, as opposed to the current 20 securely accepted drawings.

The essays are followed by catalogue entries on Wtewael’s finest paintings, highlighting the artist’s stylistic versatility in family portraits, mythological and Biblical scenes and genre works, on large and small scales and on a variety of supports, such as copper, canvas and panel. These are followed by 11 drawings that have basic tombstone information and provenance but would have benefited from full catalogue entries.

One distinguishing feature of Wtewael’s art, which the authors begin to discuss but which will hopefully encourage further study, is that many of his compositions exist in multiple copies. For example, there are ten painted versions of the Adoration of the Shepherds. This is especially intriguing given the fact that, if there had been a considerable demand for his works, Wtewael could have met it with prints, as did his Mannerist contemporaries Abraham Bloemaert and Goltzius. The extent of the artist’s involvement in the painted copies has yet to be fully understood, although there is evidence that he produced some of them himself, sometimes with alternations of colour or composition. Wtewael’s work forces us to reassess the idea of a painting as a single unique object, and reminds us that paintings too were produced in multiples during the Early Modern period.

Lelia Packer is a curatorial assistant at the National Gallery, London, where she works on the Baroque collection

Pleasure and Piety: the Art of Joachim Wtewael, is at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, until 4 October. It then travels to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1 November-31 January 2016

Pleasure and Piety: the Art of Joachim Wtewael

James Clifton, Arthur Wheelock and Liesbeth Helmus, eds

Princeton University Press, 240pp, £44.95, $65 (hb)