The London-based photographer Etienne Bol is selling his collection of 53 paintings created during the early 1970s in Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). London’s Sulger-Buel Lovell Gallery has taken consignment of the works and is exhibiting the collection for the first time until 30 June.

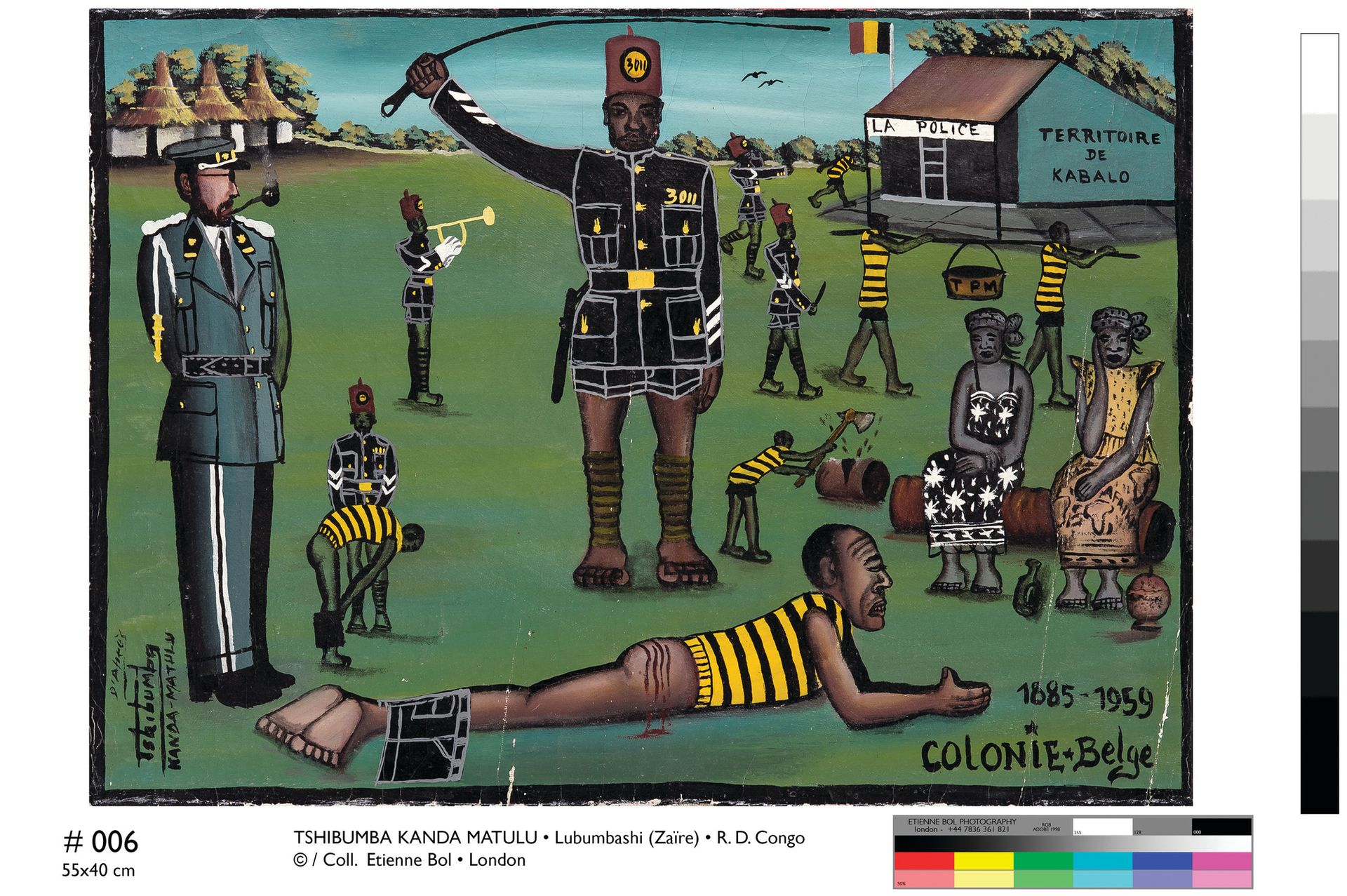

The five artists in Bol’s collection—Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, T. Kalema, C. Mutombo, Ndaie and B. Ilunga—come from the city of Lubumbashi and were part of Zaire’s Popular Painting movement, whose works depicted the country’s violent colonial history and the fight for independence. Several of these artists continue to cast a critical eye on contemporary African life.

Unlike their national counterparts such as Chéri Samba in Kinshasa, the capital of the DRC, artists from Lubumbashi “tended to see themselves as historians as well as painters, and the subjects of their works were more political”, says Salimata Diop, the head of programme at London’s Africa Centre and the curator of the show. “Their works were acquired and displayed by local city dwellers in their homes, to remind themselves of their past, of their identity.”

Christian Sulger-Buel, the co-founder of Sulger-Buel Lovell Gallery, says the market for Popular Painting is beginning to grow in the West: “There is certainly an appreciation by academics, and some feature in major European and US institutions, but they are still quite rare.”

Sulger-Buel declined to give a price for all 53 paintings, but says the aim is to sell the collection as a whole. Single works by Matulu (perhaps the best-known artist of the group) sell for between £1,500 and £6,000 at auction. The Kinshasa artists are relatively more prized—Samba’s works sell at around the £50,000 level on the primary market.

Semi-coded scenes

The collection is organised around five themes. One of the most sought after is “Colonie Belge” (Belgian colony), a genre of Popular Painting in which colonial oppression is depicted in semi-coded scenes. “For instance, a prisoner being flogged by an African policeman, while the white administrator watches on,” Diop says.

Another theme, “Usine Gécamines” (Gécamines factory), focuses on the factory and slagheap run by the Congolese metals and mineral trading company, which became a symbol of Belgium’s exploitation of the resources of Zaire. “What is more, the Gécamines factory is somehow at the origins of the town because its creation meant the beginnings of the industry, the creation of jobs,” Diop says.

The collection is accompanied by Bol’s photographs of Matulu—the only photographic record of the artist, who went missing in the early 1980s. It is thought that the political nature of his art may have contributed to his disappearance.

Etienne Bol, who was introduced to Matulu by his father, Victor, writes in the accompanying catalogue: “[Matulu’s output] is an impassioned demand for recognition of the dignity of the African man, who has too long been humiliated and oppressed. At the same time, it is a no less impassioned affirmation of the unity of the country, transcending regional and tribal differences; an exhortation to his fellow citizens to grasp their destiny, despite momentary difficulties and the possibility of injustice. In all, it is a disturbing investigation of a new social identity.”