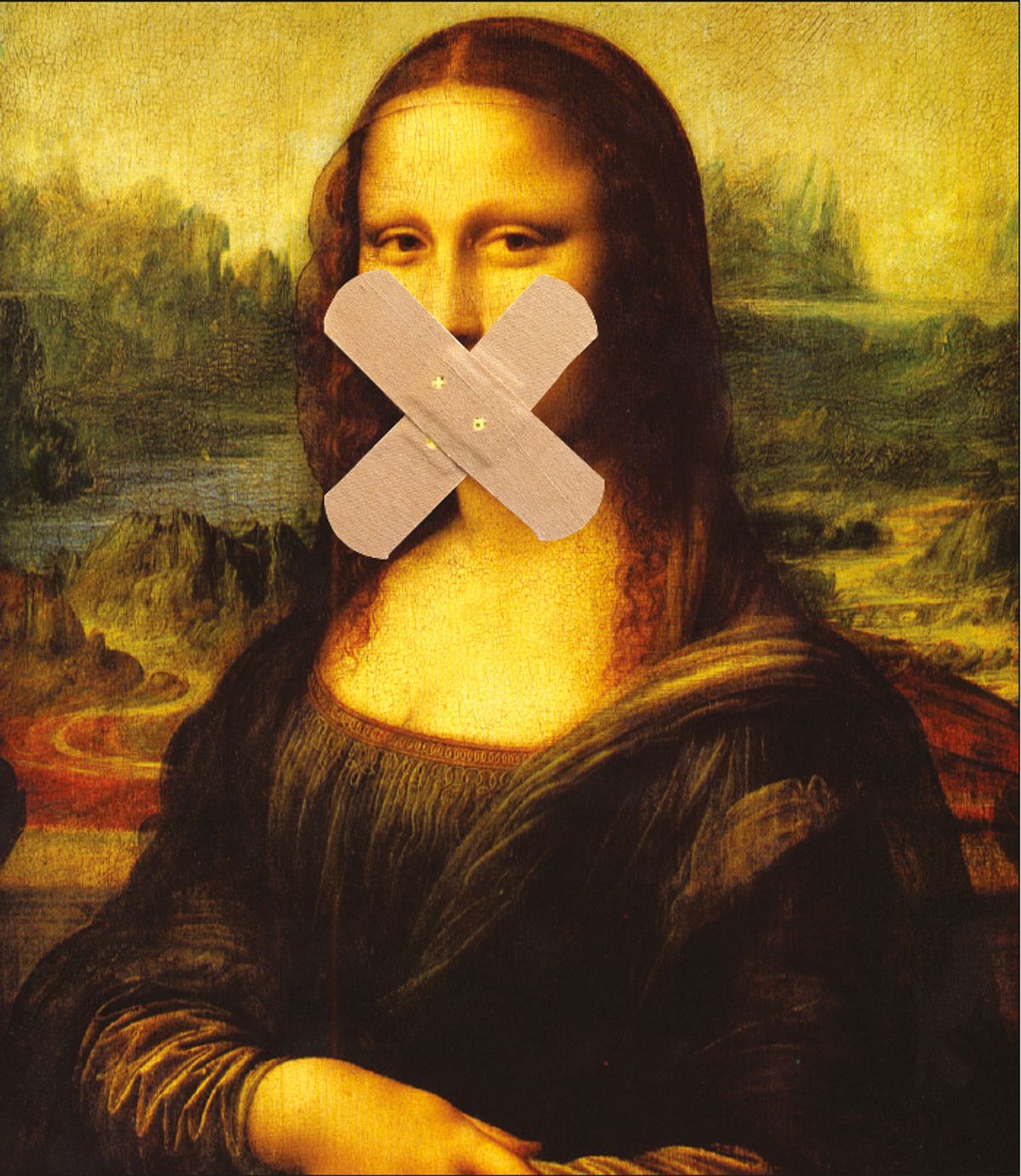

News of a grandmother’s botched restoration of a 19th-century fresco in a small church in Borja, Spain, spread through the art world like wildfire this summer. Bloggers took to their computers asking how this could have happened and what the chances are of it happening again elsewhere. Although the likelihood of a well-meaning member of the public walking into a prominent museum like London’s National Gallery, paintbrush in hand, ready to set to work on a Titian, is slim, what about works in small private collections that remain largely out of the public eye but may one day end up in a museum or national archive? Unfortunately, these pieces are all too often subjected to misguided interventions.

“In the US, you buy a Reader’s Digest so you can fix your plumbing or your gutters, so why not also try to fix your paintings?”

“Amateur restorations have always been a problem,” says Joyce Hill Stoner, a paintings conservator and professor at the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation, who has lectured on the danger of do-it-yourself restorations for more than 30 years. Before the incident in Spain, Stoner had assumed that the phenomenon was more American than European. “In the US, you buy a Reader’s Digest so you can fix your plumbing or your gutters, so why not also try to fix your paintings?” According to Stoner, a newspaper column that was popular in the 1960s and 70s advised readers on how to bleach their prints. “It was as if our profession was something that could be learned in 20 minutes,” she says.

Winterthur offers a free, monthly conservation clinic where the public can bring in works of art and get expert advice. Some of the things Stoner has seen are shocking, from a collector trying to age a frame by leaving it on the roof of his car in a rainstorm to using household cleaning products on paintings. “A geology professor tried to remove a layer of grime from a beautiful 19th-century landscape with Ajax. He scrubbed away a tree in the process,” Stoner says. “People say that they’re trying to treat their paintings and I tell them that’s like telling a doctor that they’re in the middle of taking out their own appendix,” she says.

Several years ago, Stoner met a couple who let a friend, an artist, “feed” their paintings, including a Velázquez, while they were on holiday. This involved coating the painting with linseed oil—an ill-advised practice as the oil will darken and crack over time and is difficult to remove without taking off the original paint. “People do not understand the difference between an artist’s training and that of a conservator. Becoming a mother is different from becoming a paediatrician. Artists are the parents, we are the paediatricians,” she says.

Stoner thinks the decision to do-it-yourself is often motivated by money, as collectors often “blanch” when she estimates the cost. “It’s better not to touch the work than to do something unwise,” she warns.

“People say that they’re trying to treat their paintings and I tell them that’s like telling a doctor that they’re in the middle of taking out their own appendix”

It’s not only paintings that get the do-it-yourself treatment. Mark Browne, a conservator at the British Library, often comes across photographs stuck with self-adhesive tape, which can leach into the paper. He also has to deal with over-zealous stamp collectors who bleach envelopes—a practice that darkens and weakens the paper’s structure.

Browne feels that most collectors mean well, and that the real issue is access to cheap materials. “People had the best intentions when they put their photographs in those magnetic albums that were popular in the 1980s and 90s. They didn’t realise that the plastic would degrade the photos,” he says.

One positive outcome of the incident in Spain is heightened awareness. “In some ways, we were heartbroken, but on the other hand, it has resulted in a tremendous boost in advocacy for our profession,” Stoner says.