The $8m court case between Miami collector Craig Robins and New York art dealer David Zwirner lays bare the murky intricacies of the contemporary art world (see below). The accusations reveal the secret handshakes, blacklists and verbal agreements that dominate the market, prompting some to say it is time that the whole trade opened up. A few go as far as suggesting legislation such as droit de suite, where artists receive a fee on the resale of their work, should be extended to New York.

“A reliance on keeping things hush-hush is built into the system,” said Chelsea gallerist Edward Winkleman. “If collectors’ resales did not carry a stigma, if artists benefited from the resales, and if galleries were not placed in a precarious position between two clients—the artist and the collector—the lawyers who are now going to make a small fortune off this case would be busy with more important matters.”

Linda Blumberg, the executive director of the Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA, which has a select membership of US galleries, including Zwirner), said that transparency is something the organisation “feels very strongly about. Transparency is healthy in any market. Our dealers don’t have anything to be ashamed of, so why not?” She referred to the association’s code of practice, to which all members must adhere. The document was co-written by the association’s former president Roland Augustine, who started an ethics committee during his tenure. He said that the Robins vs Zwirner case “moves everyone to clearly articulate and memorialise agreements to avoid such litigation—where there is money involved, there is always room for misinterpretation”.

“Most dealers, and some collectors, are convinced more transparency would ruin the market,” said Hans Van Miegroet, Professor of Arts and Markets at Duke University, North Carolina. “But the counter-intuitive thing is that the more transparent you are, the more profit you capture. You will also push out the less transparent people in the market and will create a more developed market overall. You basically have to share more information about everything—about the type of transactions, background on how prices were formed in the past, the type of art.”

Art investment advisors Michael Plummer and Jeff Rabin of Artvest Partners agree, adding: “One of the powers of auctions is that they set public pricing—a similar verifiable pricing mechanism for private transactions might allow record prices in this sector to be brought to the public’s attention as well.”

Nevertheless, some insiders are happy with the status quo.

Gallerist Thaddaeus Ropac said: “The fluidity of our system has its positive sides.” Revealing that his gallery does not have written contracts with its artists, he said: “Generally the handshake mentality works pretty well. It would be a pity to lose it—no one wants to feel like they are run by lawyers.”

Lucy Mitchell-Innes, president of the ADAA, said the real issue is “the relationship between collectors and dealers, which is built on trust, knowledge, and a sense of fairness. Once you interrupt that with legal documents, the basic message is that there is an erosion of trust.” New York dealer Jack Tilton, who was subpoenaed in the Robins vs Zwirner case, added: “90% of what happens in the art world is word of mouth—at the end of the day, you either trust someone or you don’t.”

Even those who are in favour of more formality concede there are practical difficulties. “You couldn’t write legislation that everyone would agree with,” said New York lawyer Peter Stern of McLaughlin & Stern, while Michael Moses, co-founder of the Mei Moses index, said: “How could you make non-public transactions transparent?”

As to droit de suite: “It’s a noble and fair idea—but also totally impossible to practice or police,” said Michael Findlay of Acquavella gallery. He added: “From an investment point of view, if I am going to share my profit with the artist, would they share the potential loss?” Todd Levin, director of the Levin Art Group, added: “Artists choose to exchange something they love, their art, for something they need, money. After choosing that exchange, they can’t attach an umbilical cord to their artwork.” But agent Richard Wadhams, of consultants Hogbens Dunphy, said that artists should be given copies of invoices for the sale of their works: “It would clarify arrangements. All artists want to know is where their work is.”

However artist Jake Chapman is sanguine about the machinations of the market: “When someone comes with the white gloves to take your work, you are paid for your efforts and that’s that.” He added: “The art world is murky, and to render it transparent is to miss the nature of its dynamic. It’s based on excessive points of disproportion—it’s a world where a Giacometti sculpture can sell for £65m. You can’t restrain the insanity of the market—that would miss the point.”

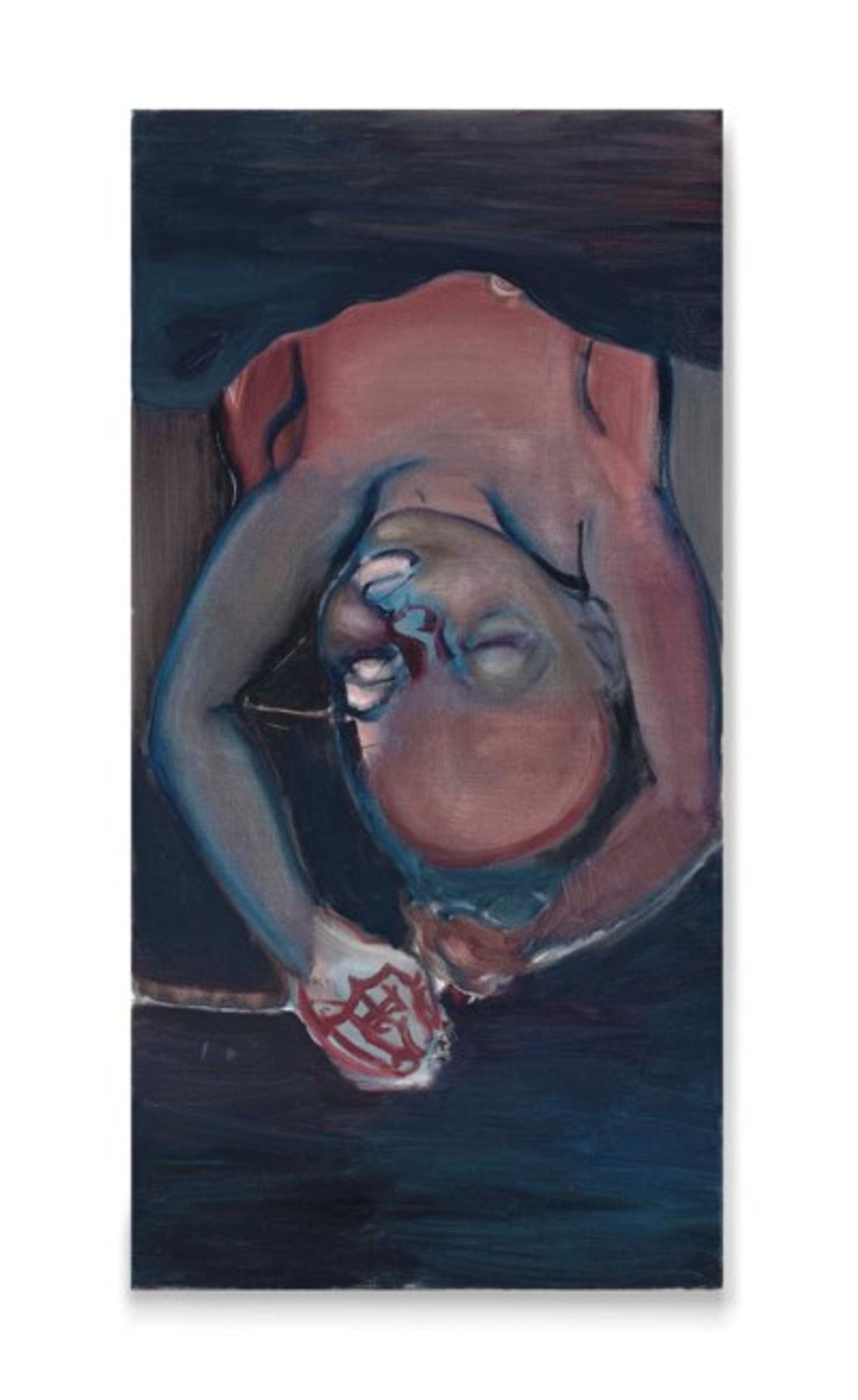

Marlene Dumas, Reinhardt’s Daughter (1994)

Anatomy of a lawsuit: who said what

In one of the more unusual cases to make it to a US court, Miami collector Craig Robins sued Chelsea gallerist David Zwirner for $8m at the end of March. Robins claimed a breach of confidentiality, after Zwirner told artist Marlene Dumas, whom he now represents, that he had sold her 1994 painting Reinhardt’s Daughter on Robins’s behalf. Robins said that the disclosure landed him on an alleged “blacklist” by Dumas, precluding him from buying her works on the primary market. He also claimed that, to avoid a lawsuit in 2005 when he first found out about the blacklist, Zwirner promised him “first choice, after museums, to purchase one or more [primary market] Marlene Dumas works”.

Robins has been a major collector of the South African artist, owning 29 works, and was eager to acquire three paintings from her new exhibition at David Zwirner. He described the artist’s latest body of work shown in “Against the Wall” (18 March-24 April) as “comparable to what the ‘Blue Period’ was to Picasso”, adding: “I could not have a complete…collection of her work without a top painting from [this show].”

Zwirner responded in court papers filed last month: “I did not enter into any confidentiality agreement, written or oral, with Mr Robins.” Zwirner also denies telling the artist—whom he did not represent at the time—to curry favour with her, as Robins alleges, but said that he acted “in accordance with Dumas’s expectation of being informed of such sales and to inform her that the new owner would be willing to loan Reinhardt’s Daughter for important exhibitions”. In his court papers, Zwirner also said: “I never promised…Mr Robins that I would sell him a painting…I did not represent Marlene Dumas at that time and could not possibly have made any promises in regards to her work.”