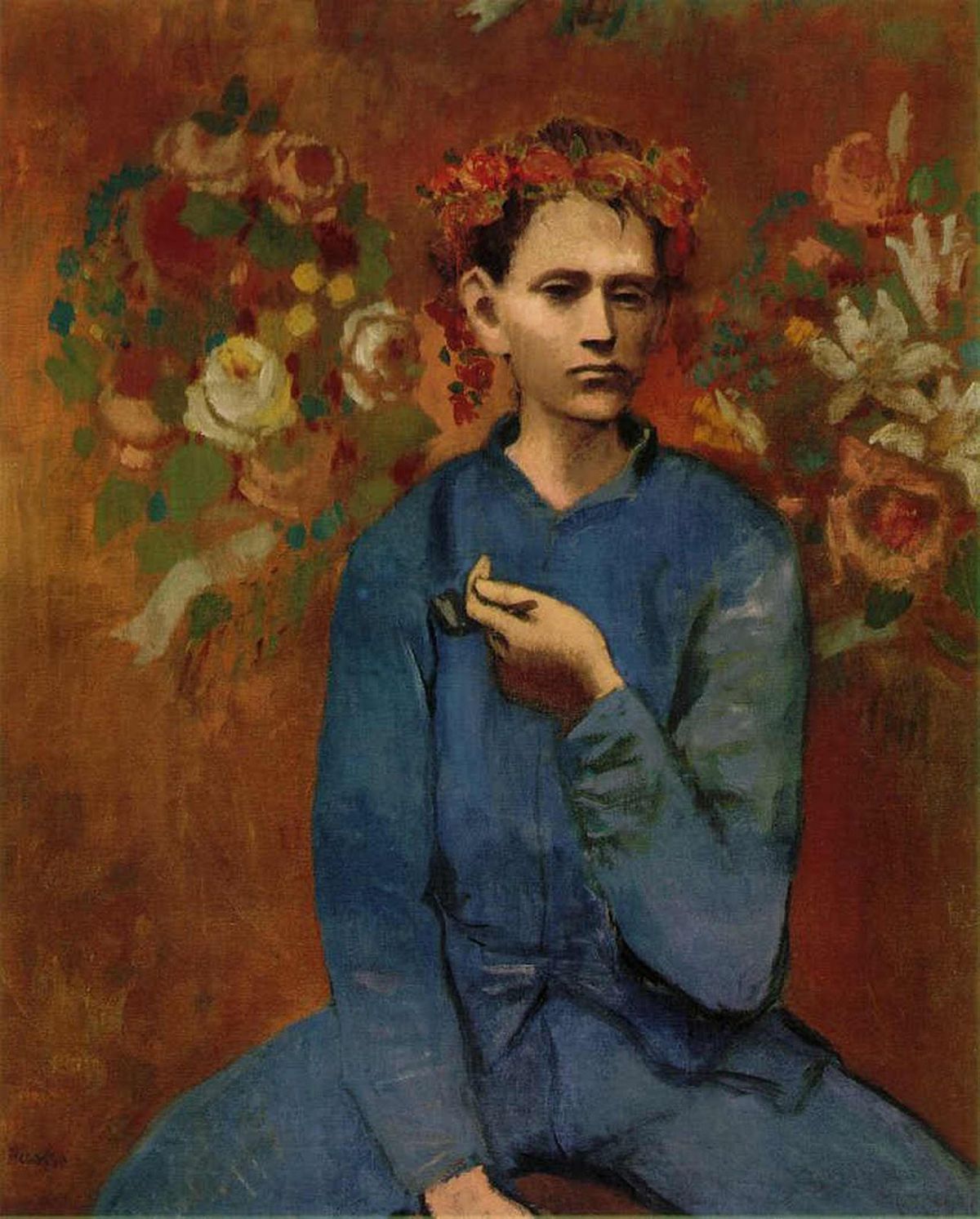

In the space of just two years, three immense prices have been paid for works of art. Picasso’s Garçon à la Pipe (1901) became the first painting to break the $100m auction barrier, making $104.5m in 2004. Two months ago, Picasso’s Dora Maar au Chat (1941) set the second highest price when it sold at auction for $95.2m. Then last month Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Block-Bauer (1907) was sold for $135m to Ronald Lauder. It is believed that other recent private deals have also been in excess of $100m.

The sale of Garçon à la Pipe ended the long reign of Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr Gachet (1890) as the world’s most expensive work of art, a reign which lasted for 16 years. So is this sudden explosion of prices an indication of an accelerating trend or rather is it a reflection of the cyclical nature of the art market?

Today’s art boom is not the first. In 1914, the world gasped when the Russian Tsar Nicholas II snaffled Leonardo’s Benois Madonna, (1475-80) (now in the Hermitage Museum), from under the nose of Henry Clay Frick. The Tsar paid $1.5m in 1914, the equivalent of about $41m today. This purchase was the apotheosis of an intense art boom from 1910 to 1914, brought to an end by the First World War, which saw American buyers including Isabella Stewart Gardner, Pierpont Morgan, Henry Huntington and Frick vying for Old Master paintings. The Leonardo was to remain the most expensive work for another 56 years, until Velázquez’s Juan de Pareja (1650) sold to New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art for over £2.3m in 1970, the equivalent today of £46.6m.

But these prices were overtaken during the next art boom from 1987 to 1990. It started with the sale by Christie’s, in 1987, of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888) to a Japanese insurance company, for $39.9m. This started a billion-dollar binge: while Japanese buyers had bought heavily on the Western art market in the early 20th century, this new splurge was by a post-war generation riding high on the Japanese economic “miracle”. The boom continued until May 1990, when a Japanese paper mogul bought Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr Gachet for $82.5m and, two days later, Renoir’s Au Moulin de la Galette (1876) for $78.1m. The sales marked both the climax and the end of the boom. With the collapse of property prices, the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and the revelation in Japan that art was being used to evade tax, the Japanese suddenly stopped buying and the art market went into freefall.

Today, the art market is again booming. New buyers are entering the market, while supply—the perennial problem—is improving as vendors release works that have been off the market for generations, in expectations of top prices. Picasso’s Dora Maar last sold in 1963; his Garçon à la Pipe in 1950. The restitution of war-looted property to its rightful owners is also having an impact: Klimt’s Adele Bloch-Bauer was recently returned to the vendor, Maria Altmann, after hanging in the Austrian National Gallery since 1948.

Compared with the 1980s boom, there are two differences. Then, the market was dependent on Japanese buying, and many were borrowing to buy art. Today’s buyers are spending their own money—and they have lots of it. The past three years have seen a colossal increase in wealth globally. Forbes’s 2006 list of the world’s billionaires counts 793 people, three times as many as in 2003. And they are spread through 54 countries including four in Kazakhstan and eight in China.

So how long can this boom last? Without a major geo-political jolt, it seems set to last for at least another year, but there are a few signs that it is slowing. Buyers at Art Basel were protesting about the high prices, and last month’s sales of contemporary art in London scarcely bettered those of last year. All markets have cyclical phases but the art market overall is showing steady growth.