Thieves do not usually leave full documentation of their thievery, but the massive thefts by the Nazis from the Jews are recorded in every detail; this was not just the banality of evil, to use Hannah Arendt’s famous phrase, but the bureaucracy of evil.

The author of this important and large book has sifted through the 50,000 declarations of possessions, the 100,000 files in the Austrian ministry of finance and 16,500 applications for permission to export relating to the expropriations that occurred between 1938, when the Germans took over Austria, and the end of the war in 1945. Sophie Lillie has done this with financial support from, among others, the Austrian government, which has said that it wants to right the wrongs of the past, and in a number of cases has done so, but is being obstructive in others, as over the Bloch-Bauer Klimts.

In the process of her researches, Dr Lillie reveals the enthusiasm and rigour with which some art-historian functionaries of the Austrian State—for example, Dr Josef Zykan and Dr Waltraude Oberwalder of the Zentralstelle für Denkmalschutz (head office for the protection of the patrimony)—collaborated with the Nazis to enrich the public collections of which they were custodians—a warning to museum curators of all times not to allow their collecting passions to overcome their respect for human rights.

In presenting the life histories and inventories of 145 Austrian Jewish individuals and families whose collections were looted, Dr Lillie has achieved three things, all of them important.

First, she has given us an astonishingly vivid picture of the assimilated, haut bourgeois Jewry of Austria between the wars , people who without exception were talented, successful members of the community, many of them with official positions or with State honours (for example, Gustave Arens, textile manufacturer, Knight’s Cross First Class, Officer of the Franz Joseph Order).

And then, in less time than separates us today from the 11 September attacks, their lives were turned into the hell with which we are all familiar, a story that should remind us how the price of defending liberal values and humanity is constant vigilance.

Among these life stories are some names famous in the arts: Alma Mahler-Werfel, herself a composer, but also married to Gustav Mahler, then Kokoschka’s lover, then wife of Walter Gropius, and finally, wife of the novelist Franz Werfel; the composer Zemlinsky, teacher of Schoenberg; Otto Kallir, picture dealer and grandfather of Jane Kallir, today a well known dealer and scholar in New York.

Second, Dr Lillie has explained the Kafkaesque system for the confiscation of goods, which usually worked like this. When a Jew applied to emigrate, in theory only 25% of his goods went to the State. An inventory was submitted and the Zentralstelle für Denkmalschutz decided which works of art were of national importance and these were “made secure”, ie; confiscated. It was rare, however, for what was left to be reunited with the owner, who had usually already fled to an unknown destination. Instead, it sat in Nazi-owned warehouses, which sold the goods to pay the “storage charges” that the owner obviously could not cover.

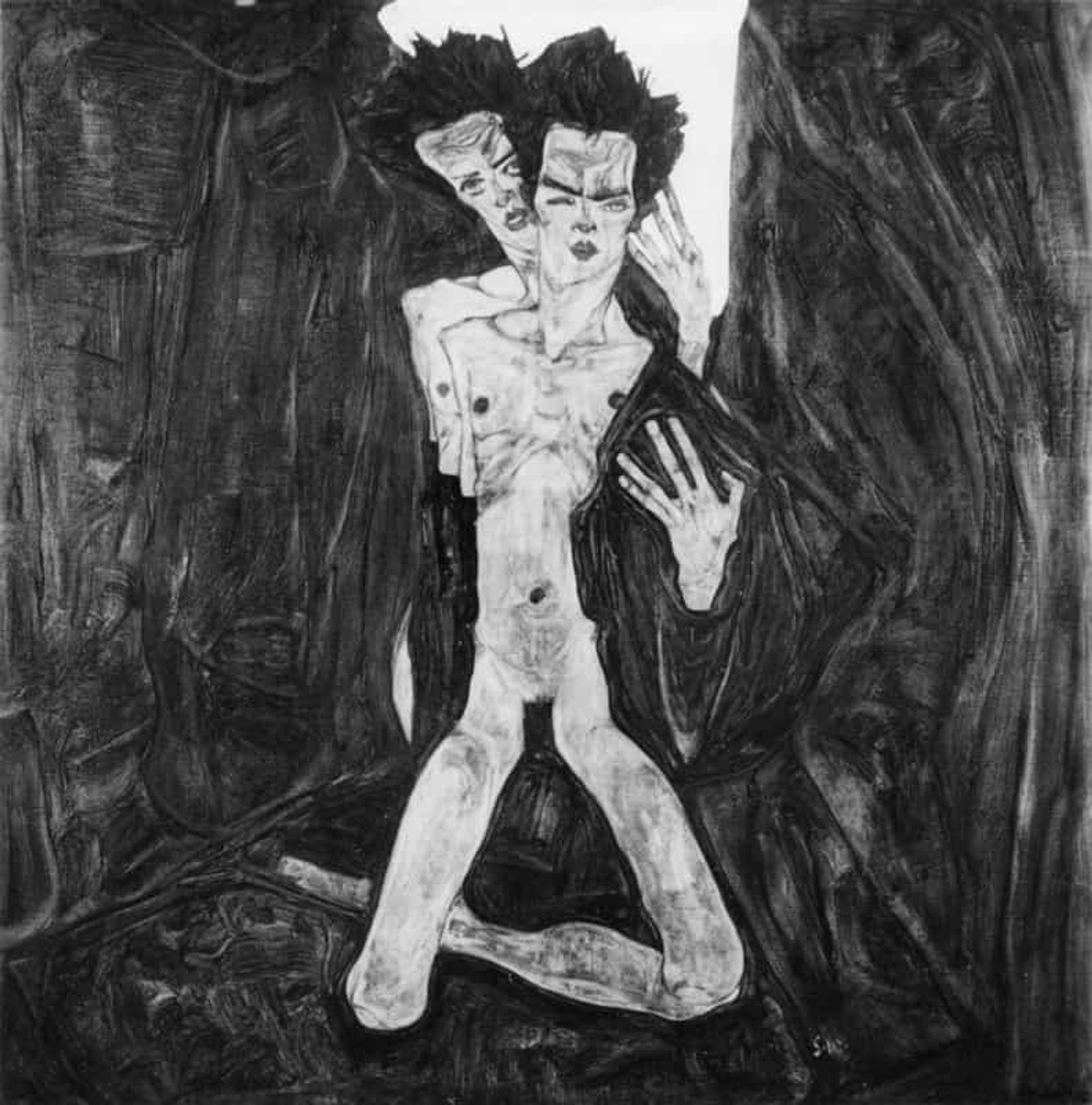

Egon Schiele’s “Die Selbstseher I”, formerly in the collection of cabaret artist Fritz Grünbaum. Present whereabouts unknown Photo: courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, New York

A frequent penalty for emigrating was to be stripped of citizenship, and at this point all goods fell to the State, which would sell them as “property of a Jew” through the State-owned auction house, the Dorotheum, or the dealership of VUGESTA, the branch of the Gestapo responsible for the valuation of emigré goods. This part of the book, together with the inventories, will certainly help descendants of the victims to track down their family possessions.

The inventories are the third reason why this book is fascinating and important, because it gives an extraordinarily complete idea of the taste of the period in Vienna. The collections of pre-20th-century art are in the majority, many of them as rich in decorative arts (Renaissance bronzes, maiolica, textiles, etc.) as paintings and sculpture. Nineteenth-century Austrian painting is strongly represented also, but it is the collectors of 20th-century Viennese art, Klimt, Schiele, Kokoschka, who are most in tune with today’s interests and market values: Heinrich Rieger, Oscar Reichel, Serena Lederer, the Zuckerkandl family, Ferdinand and Adele Bloch-Bauer.

Maria Altmann, niece of the Bloch-Bauers this June won a legally important victory in the US Supreme Court, which decided that Austria and the Österreichische National Galerie can be sued in the US courts for the return of six Klimts stolen by the Nazis (see p.7).

After the war, efforts were made by the Allies to return works of art to their owners, but by 1950 history was felt to have moved on and the various authorities responsible for this process were wound up.

A renewed process of restitution began in the mid 1990s. Dealers and auction houses, but also museums, now look carefully to see what the history of any work of art might have been for the crucial years between 1933 (1938 for Austria) and 1945 (see pp.23, 28). The Art Loss register database provides a search service, and independent researchers will comb through public and documents to find these stolen works.

Many works tainted by this vile period in history are still in circulation, and some are still in public collections. The illustrations of this book are nearly all of these, and of pieces the current whereabouts of which are unknown.

The dispossessed

Leon and Marianne Abramowicz, Bernhard Altmann, Hans and Helene Amon, Otto and Clara Anninger, Gustav Arens, Fritz and Anna Unger, Felix and Lise Haas, Carl and Rosa Askonas, Stefan Auspitz, Theodor and Angela Auspitz-Artenegg, Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt, Richard and Paula Beer-Hofmann, Ernst and Irma Benedikt, Ludwig Bettelheim-Gabillon, Rudolf and Martha Bittmann, Josef and Gusti Blauhorn, Hugo and Malvine Blitz, Wilhelm and Gertrude Blitz, Ferdinand and Adele Bloch-Bauer, Victor and Alice Blum, Oscar Bondy, Julius and Paula Breuer, Otto and Lilly Brill, Julius and Margarethe Buchstab, Paul and Mary Cahn-Speyer, Edwin and Caroline Czeczowiczka, Arthur and Irma Czeczowiczka, Georg Duschinsky, Ernst and Fanny Egger, Lothar and Eveline Egger-Möllwald, Alfred and Valerie Eisler, Hermann and Hortense Eissler, Berta Morelli, Hans and Lucie Engel, Viktor and Emilie Ephrussi, Charlotte Epstein, Rudolf Ernst, Gertrud Felsöványi, Adele Fischel, Josef Freund, Wilhelm Freund, Hugo and Hilde Friedmann, Hermann and Elsa Gall, Paul and Martha Gerngross, Robert and Frida Gerngross, Emil Geyer, David and Lilly Goldmann, Philipp, Cornelia and Marie Gomperz, Fritz and Lilly Grünbaum, Karl and Stephanie Grünwald, Rudolf and Marianne Gutmann, Leo and Helene Hecht, Valerie Heissfeld, Wilhelm and Daisy Hellmann, Franz and Marie Louise Herzberg, Fritz and Gertrud Hirsch, Ernst and Martha Hirsch, Adolf and Hilda Hochstim, Franz Josef and Vally Honig, Josef Franz and Hermin Hupka, Bruno Jellinek, Otto and Fanny Kallir-Nirenstein, Siegfried and Irma Kantor, Emil and Helene Karpeles-Schenker, Irma Ketschendorf, Benedikt and Emilie Klapholz, Norbert and Serafine Klinger, Isidor and Camilla Kohn, Nettie Königstein, Felix Kornfeld, Gottlieb and Mathilde Kraus, Wilhelm Viktor and Marianne Krausz, Hans Krüger, Moriz and Elsa Kuffner, Stephan Kuffner, Wilhelm and Camilla Kuffner, Adele Kulka, Wally Kulka, Oscar L. Ladner, Richard and Anna Lanyi, Georg and Hermine Lasus, August and Serena Lederer, Rosa Lemberger, Mathilde Lieben, Leon and Antonie Lilienfeld, Markus and Melanie Lindenbaum, Fritz and Helene Löhner, Arthur and Marianne Lourié, Wilhelm and Fanny Löw, Oscar and Irma Löwenstein, Alma Mahler-Werfel, Fritz Mandl, Stephan and Else Mautner, Edmund and Adele Mendelsohn, Franz Mendelsohn, Alice Meyszner, Max and Hertha Morgenstern, Aranka Munk, Oskar and Therese Neumann, Richard and Alice Neumann, Gabriele Oppenheimer, Ignatz and Gisela Pick, Moric and Irma Pick, Otto and Katharina Pick, Ernst and Gisela Pollack, Albert Pollak, Robert and Adele Pollak, Leopold Popper-Podhragy, Ernst and Ilse Popper-Podhragy, Arthur and Agnes Prager, Julius and Camilla Priester, Leo Prister, Alfred Quittner, Amalie Redlich, Anton and Marie Redlich, Paul and Therese Regenstreif, Oskar and Malvine Reichel, Arnim and Rosa Reichmann, Heinrich Reif, Andreas and Luise Reisinger, Franz and Anna Riedl, Heinrich and Berta Rieger, Max Roden and Sascha Kronburg, Heinrich and Ella Rothberger, Moriz Rothberger, Alphonse and Clarice Rothschild, Louis Rothschild, Franz Rothschild, Franz Ruhmann, Emma Schiff-Suvero, Gustav and Louise Schoenberg, Ludwig and Gertrude Schüller, Eduard and Gisela Schweinburg, Arnold and Margit Löffler, Elkan and Abraham Silberman, Josef and Louise Simon, Marianne Singer, Alfred and Irmgard Sonnenfeld, Valentine Springer, Jenny Steiner, Klara Steiner, Paul and Nora Stiasny, Georg Terramare and Erni Terrel, Alfons and Marie Thorsch, Siegfried and Antonia Trebitsch, Alexander and Irma Weiner, Leopold Weinstein, Josefine Winter, Paul Wittgenstein, Fritz and Annie Wolff-Knize, Frank and Mary Wooster, Alexander and Luise Zemlinsky, Paul Zsolnay, Fritz and Trude Zuckerkandl

• Sophie Lillie, Was einmal war: Handbuch der enteigneten, Kunstsammlungen Wiens (Czernin Verlag, Vienna, 2003) 1,440 pp, 354 b/w ills, €69 (hb), ISBN 3707600491