On 25 February, the US Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the case of Maria V. Altmann who is attempting to sue Austria and the Austrian National Gallery (ANG) in the US for the return of six paintings by Gustav Klimt which Nazis stole from her uncle in Vienna. The court will issue a ruling by the end of June.

A yes vote from the court is vital to the continuation of the lawsuit, which Austria has unsuccessfully sought to dismiss as impermissible in two lower federal courts. If the Supreme Court accepts Austria’s final appeal, Mrs Altmann’s claim, which has focused an international spotlight on Austria and the Klimt paintings, will be over forever in US courts.

The justices will not decide who owns the Klimt paintings. Indeed, it was almost 53 minutes into the one-hour argument before the words “property taken from a Jewish family” were even heard in the courtroom. Instead, the question is whether Austria, a sovereign nation, can be sued in US courts over events that predate 1976, when the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA) was enacted, newly permitting lawsuits against foreign nations in certain specified cases.

Austria says the statute cannot be “retroactively applied” to permit lawsuits based on pre-1976 events. The actions surrounding the paintings took place in and before 1948 (see below). However, the plaintiff, Maria V. Altmann, says that the suit is permitted because the paintings have been wrongly withheld by the ANG “in violation of international law,” one of the exceptions to immunity contained in the FSIA. The statute, she says, does apply to pre-1976 events.

Altmann’s attorney convinced two lower federal courts to let the suit proceed despite Austria’s immunity protest.

The ANG and Austria are represented by the major US law firm Proskauer Rose in Los Angeles. The Bush Administration has filed a brief supporting Austria.

In a packed courtroom on 25 February, Mrs Altmann (88) was present with her four children. Austrian officials, including the Ambassador to the US Eva Nowotny, also attended. Proskauer partner Scott P. Cooper argued Austria’s case.

Applying the FSIA in this case would unfairly create new “legal consequences” to Austria for 1948 events, Mr Cooper argued, and the “retroactive” application of a new law was not permitted.

Before 1976 “there was complete immunity in this country for claims of expropriation,” Mr Cooper said, and foreign sovereigns had an expectation that they would not be sued in the US for their internal sovereign activities.

But Justice Antonin Scalia questioned whether such expectations were protected. Suppose, Justice Scalia said, “I expected not to be able to be sued in Virginia,” and Virginia changed its law allowing a suit. “I can’t believe that Austria when it took this action had in mind, ‘I can’t be sued for this in the United States,’’ he said. “Who cares?”

But Mr Cooper argued that Austria “absolutely” could not have been sued in any country over expropriations before 1976.

Arguing for the Bush Administration, Deputy Solicitor General Thomas G. Hungar of the Department of Justice said the government has always maintained that sovereign immunity bars US courts from adjudicating pre-1976 expropriation claims. Suits against foreign sovereigns “are frequently sources of friction,” Mr Hungar said, and should be addressed diplomatically.

But while some of the justices raised issues of international reciprocity, Justice Stephen G. Breyer asked whether the FSIA could still permit a lawsuit despite foreign policy issues. “Where am I wrong in thinking there is no real foreign policy concern here?” he said. He asked why the State Department could not just file a “statement of interest” telling courts to “stay out” of a case where there was a “big foreign policy matter” being worked out in other forums rather than barring such lawsuits as a jurisdictional matter.

Mr Hungar said that this course of action could lead to claims against “countless foreign countries,” citing current lawsuits in the US against Japan and Poland.

But Mrs Altmann’s lawyer, E. Randol Schoenberg of Burris & Schoenberg, Los Angeles, told the court his case would not open US courts to such suits.

Justice David H. Souter cited the government's concern about foreign relations embarrassment. Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist asked Mr Schoenberg if those foreign relations concerns were not “conclusive.” Justice Breyer asked if US courts should adjudicate expropriation claims from “all over the world.”

But Mr Schoenberg said other suits would be barred, by time limits, defenses of inconvenient forum and interference with treaties, and the “Act of State” doctrine, under which US courts cannot rule on actions taken by foreign sovereigns within their own territory. Austria has not claimed the Act of State defense in this case. Under the Austrian State Treaty, Schoenberg added, “Austria must return property taken from Jewish families in the Nazi era.”

By the argument’s close, it appeared to some that while the justices had asked close questions of Austria’s lawyer, and listened respectfully to the attorney for the US, some of the justices seemed to be collaborating with Mr Schoenberg in addressing the thorny problem of how to balance foreign relations concerns with allowing such a lawsuit.

Others flatly predict that the Court will never allow the case to go forward given US executive branch concerns.

When the justices rose, Ruth Bader Ginsberg led the way out the left rear door, followed by Justices Souter and Scalia, neither talking to the other. The nine justices will now meet in closed session to deliberate.

Case history

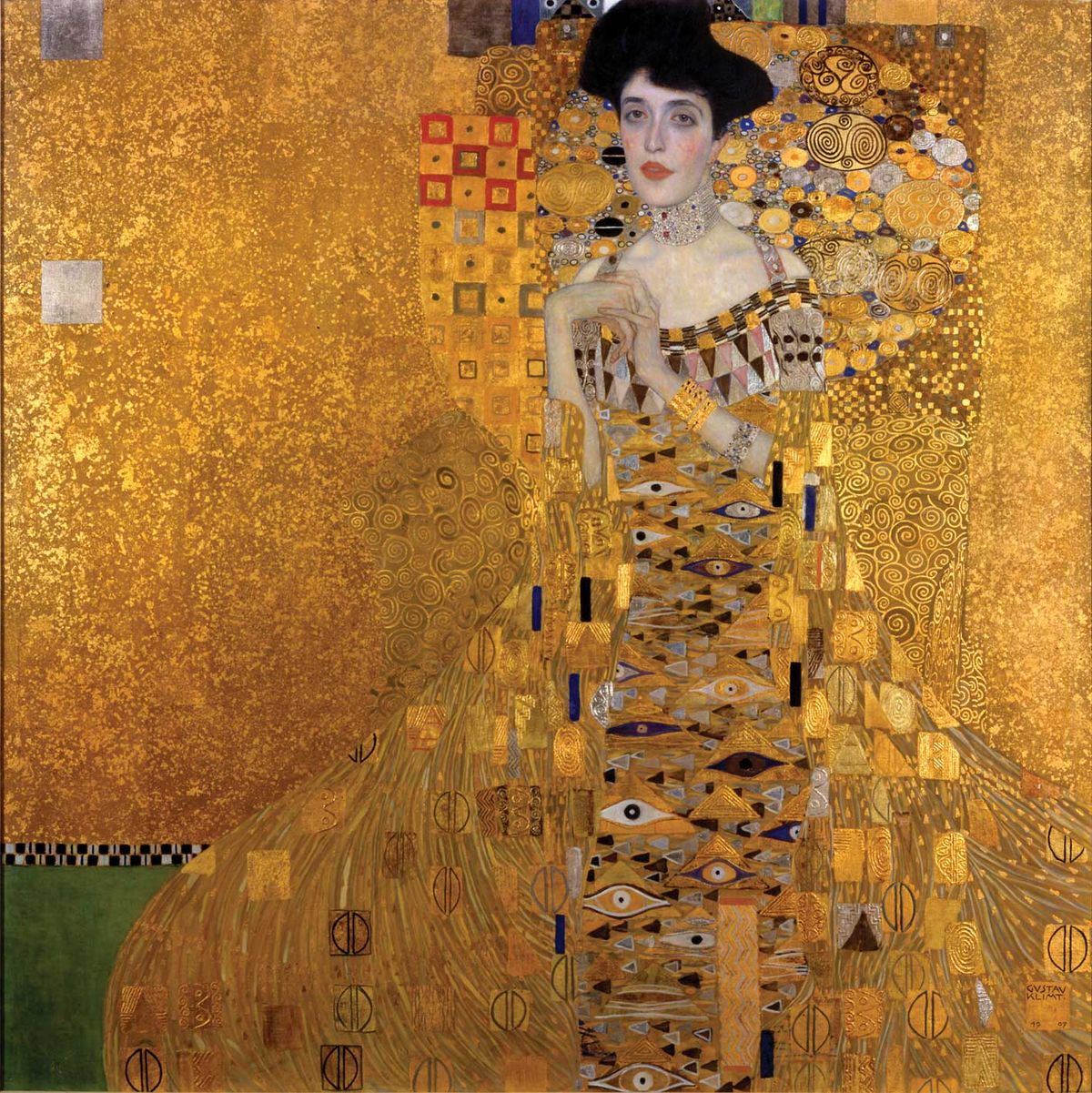

The art: Six paintings by Gustav Klimt now on view at the Austrian National Gallery (ANG), said to be more than $100 million.

Former owner: Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, wealthy Jewish sugar magnate in Vienna. His wife, Adele Bloch-Bauer, is famously portrayed in two of the paintings. Adele died in 1923, leaving a will “kindly” asking Ferdinand to give the six Klimts to the ANG on his death. This was not a bequest, Altmann says.

The Second World War: The Nazis stole the paintings from Ferdinand’s home after Austrian annexation in 1938. Ferdinand escaped to Switzerland. The Nazis then gave two paintings to the ANG, purportedly following Adele’s will. Four others were kept or given to Austrian museums. Ferdinand died penniless in Switzerland in 1945, leaving his property to his heirs.

After the war: The ANG cited Adele’s will to keep the paintings, despite allegedly possessing an internal letter saying it had no legitimate claim to own them. Austria used export control laws to force emigrating Jews to “donate” art to the nation when they sought the official permits required to take the rest of their collections with them. The lawyer for Ferdinand’s heirs, allegedly without authorisation, and anticipating Austrian delay tactics to keep the Klimt paintings, gave all six paintings to the ANG to obtain the permits the family needed to export the rest of Ferdinand’s collection.

• This article originally appeared in The Art Newspaper with the headline "US Supreme Court hears the Austria Klimt case"

• Click here for commentary on the case by Erika Jakubovits, executive director of the Jewish Community of Vienna.