A “lost” European painting of Christ which was for centuries the icon of the Ethiopian emperors has been tracked down by The Art Newspaper. The almost legendary panel is among the world’s most important paintings in historical terms. It was carried into battle by the Ethiopian emperors and their noblemen swore allegiance beneath the crowned figure of Christ. Few paintings have a more extraordinary history than the revered panel known as the Kwer’ata Re’esu, or “the striking of the head”.

The origins of the imperial icon remain mysterious, but it was probably painted in Flanders or Portugal in the 1520s and then taken to the mountainous outpost of Christianity in Eastern Africa. It is also possible that the panel was painted in Ethiopia by a visiting Portuguese artist. Despite Jesuit efforts to convert the Ethiopians, they kept to their traditional Orthodox faith. Yet it was this Catholic image of Christ which was worshipped as a sacred icon. A European painting became a potent symbol for one of Africa’s greatest empires, ruled by a dynasty which traced its origins back to King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.

Centuries after its acquisition, Ethiopia was robbed of its treasured picture. In 1868 the Kwer’ata Re’esu was looted by Richard Holmes, a British Museum keeper who had been dispatched to bring back Ethiopian antiquities and manuscripts. He was attached to Robert Napier’s military expedition against Emperor Theodorus, who was at his mountain fortress at Maqdala (Magdala). Holmes seized the painting from above the emperor’s bed, just minutes after Theodorus had shot himself. But instead of handing the Kwer’ata Re’esu over to the British Museum, Holmes secretly took it for his private collection. Since then the sacred panel has been almost as elusive as the mythical kingdom of Prester John.

Discovery of the Imperial Icon

The Art Newspaper has now tracked down the Kwer’ata Re’esu to a private collection in Portugal. Stored in a bank vault, it is still in the original wooden box in which it was shipped from London in 1950, with the painting wrapped up in the 20 April issue of the London Evening News. We were able to examine the painting and to photograph it, and this has revealed much more about its astonishing history. The owner has requested anonymity.

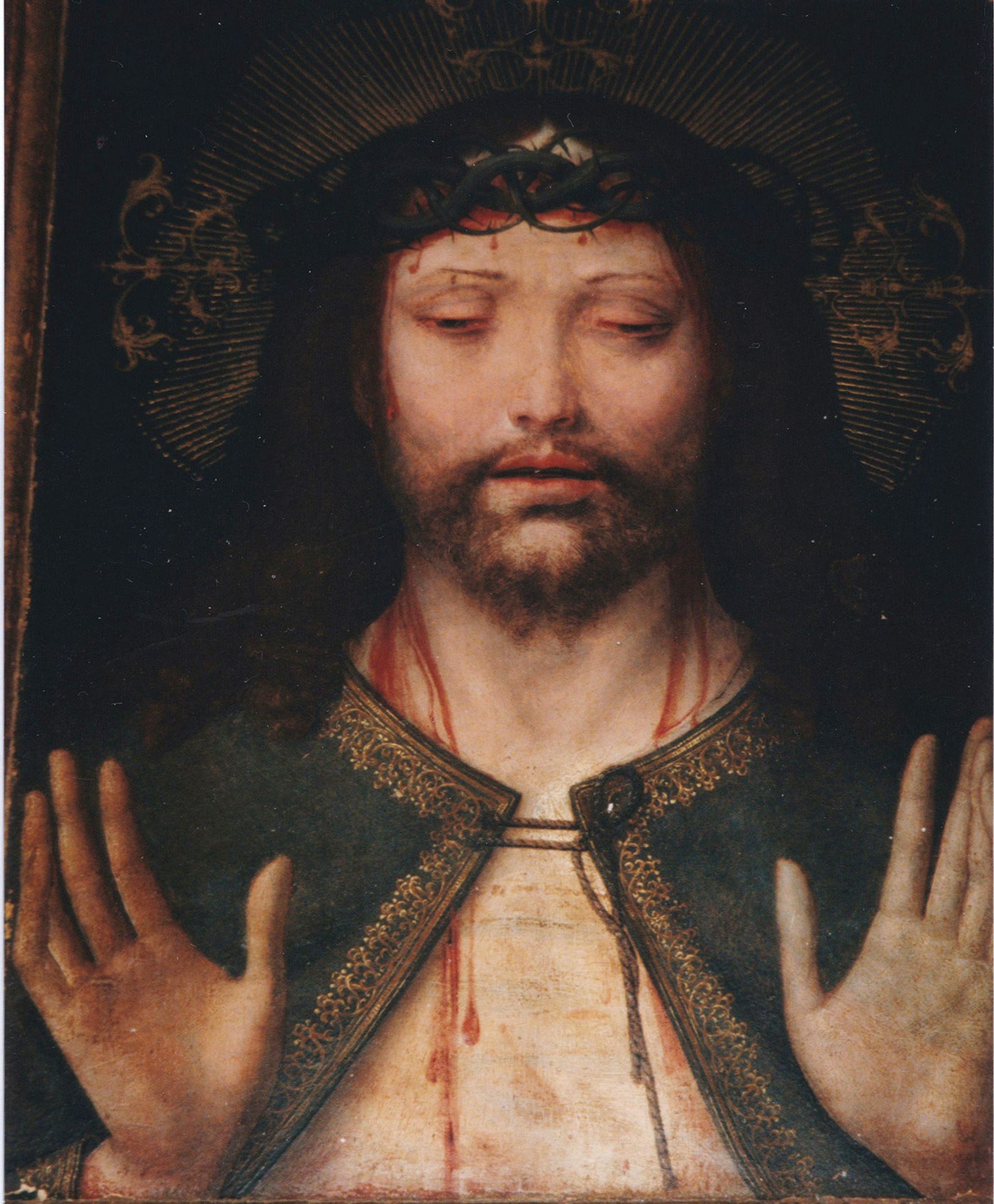

The painting depicts Christ wearing the Crown of Thorns, with blood from his pierced brow streaming down his chest. His palms are raised, and his intense eyes are downcast. Particularly striking are the hands, which are not quite symmetrical. The scene shows the end of Christ’s trial, just before he was led away for the crucifixion. As recorded in Mark 15: “They clothed him with purple, and plaited a crown of thorns, and put it about his head. And began to salute him, Hail, King of the Jews! And they smote him on the head.”

On stylistic grounds, the dating of the Kwer’ata Re’esu to around 1520, proposed by earlier art historians, seems correct. The picture is certainly Netherlandish in style, although it could have been done in Portugal by a painter emulating the Northern artists. Indeed, experts in London who have seen our photographs believe that it may well be Portuguese. A close examination reveals evidence of underpainting: the head of Christ originally seems to have been slightly narrower, and this is clearest in the area of the hair. The panel, probably oak, measures 33x25 cm.

On the dark background, in the two upper corners, is a faded inscription. Written in Ge’ez, the ancient language of the Ethiopian church, it has been translated as “How they struck the head of Our Lord”. On palaeographic grounds the Ge’ez text has been dated to the early seventeenth century, and possibly earlier. Our examination of the painting suggests that the inscription is now considerably more faded than it was in the black-and-white photograph taken nearly a century ago. This is strong evidence that the inscription was added in a quite different type of paint.

A second photograph of the Kwer'ata Re'esu taken by Martin Bailey in 1998 when it was still in its 1950 packing case. It was not published in colour until 25 September 2023 Image may be reproduced, with the credit: Martin Bailey (photograph), The Art Newspaper. Contact: info@theartnewspaper.com

The Kwer’ata Re’esu is in remarkable condition, considering its many vicissitudes, including its probable voyage from Portugal to Ethiopia in the early sixteenth century, its incursions into numerous battlefields, its capture by Muslims in the Sudan in the eighteenth century, the fighting at Maqdala, and Holmes’s trek back to London. There are just a few, small, retouched paint losses, such as one below the right side of the halo, but these do not seem to have worsened since the early black-and-white photograph. A diagonal crack in the paint has developed downwards from the left corner of the mouth. There is surface dirt and the colours have darkened. For example, Christ’s cloak may once have been purple, as recorded in the Gospel of Mark. In 1905 the cloak was described as a “deep cool blue”, but it is now a dark greenish-blue and close in tone to the background.

Our examination has revealed that the painting survives in its original frame. It is a Netherlandish-type example of the early sixteenth century, with a sloping base, and the gilding is worn. The original frame is now enclosed in a second frame, probably nineteenth century. This must have been added for protection or in effort to enhance the visual impact of the painting.

The back of the panel is particularly interesting. It is covered with red silk which has a pattern of stylised foliage. On the basis of our photographs, Linda Woolley at the Victoria and Albert Museum suggests that it is Italian material, probably dating from the late sixteenth or early seventeenth centuries. Italy had trade links with Ethiopia until the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1634, so the silk could have arrived directly or via Portugal. Curiously, the silk on the back of the Kwer’ata Re’esu continues around the side and partially covers the front of the frame. This suggests that the painting might once have been covered with a curtain in the same material.

The other surprise on the reverse of the Kwer’ata Re’esu is an inscription by Holmes, written in ink on the red silk: “R.R. Holmes/FSA [Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries]/Magdala/13 April 1868/taken from the palace of Theodorus.” This unpublished text confirms that the picture was seized by Holmes immediately after the emperor’s suicide, and was acquired before the official auction of the “spoils”. Our search of archival material has confirmed that Holmes instituted a cover-up on his return to London.

The rediscovery of the Kwer’ata Re’esu is likely now to stimulate Ethiopian efforts to recover the picture. There are few other instances anywhere in the world where an individual painting has been so intimately bound up with the history of a nation.

Nearly five years ago The Art Newspaper published an article about the Kwer’ata Re’esu by Ethiopian historical specialist Stephen Bell, under the headline “Where is this painting now?” (November 1993). Mr Bell, who is writing a book on the battle of Maqdala, is delighted with the rediscovery: “The Kwer’ata Re’esu should be returned to Ethiopia, because of its pivotal importance to the country over so many centuries. It is of equivalent historical significance as the Crown Jewels are to Britain, but it also has a religious dimension.”

From Catholic gift to Orthodox icon

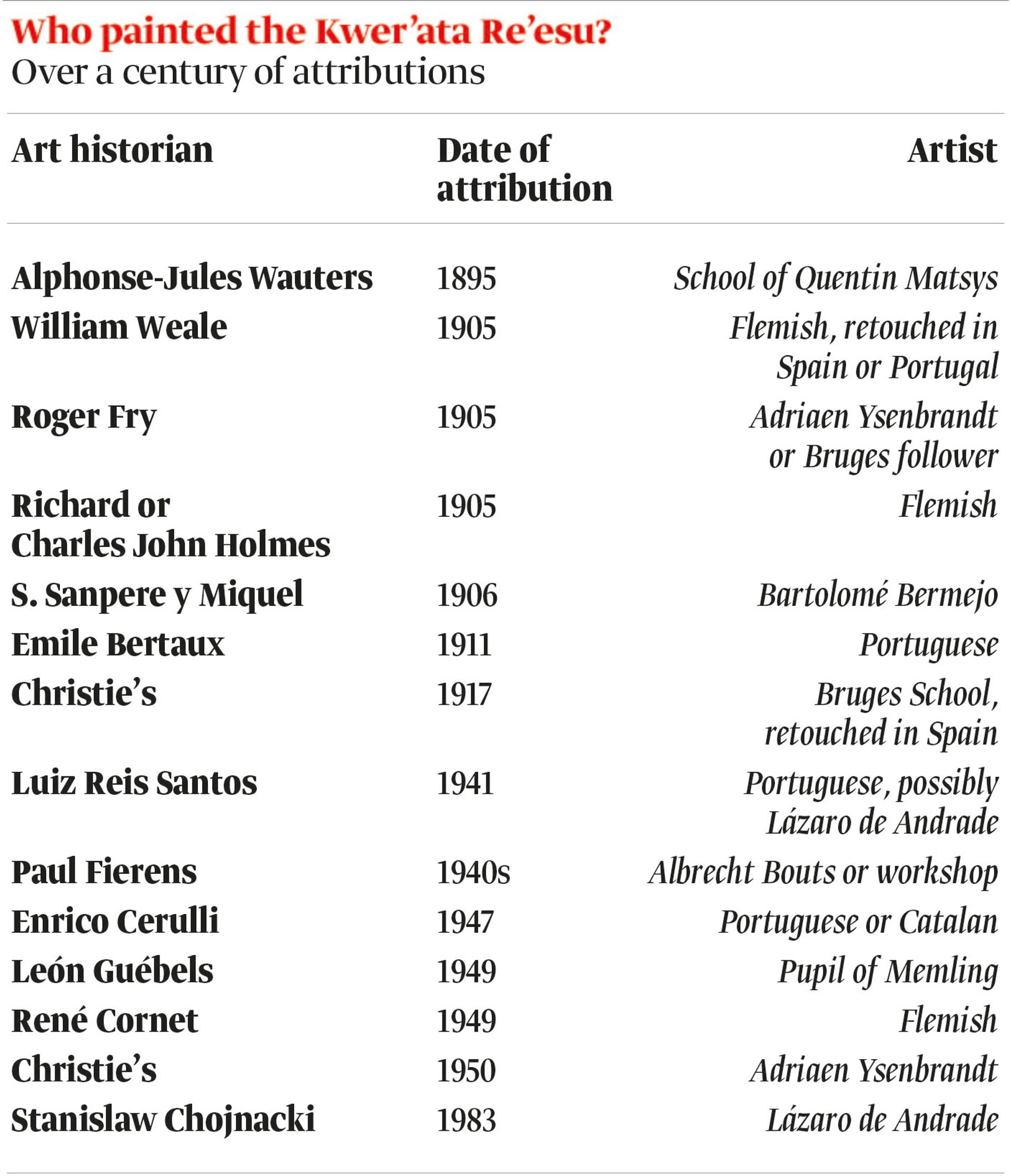

The first mystery which the rediscovery should solve is where the Kwer’ata Re’esu was painted: Flanders, Portugal or possibly by a Portuguese artist in Ethiopia. So far there has been a notable tendency for Northern art historians to claim it as Flemish and Iberian art historians as Portuguese, but most of the attributions have been made on the basis of the early photograph. Artists who have been proposed include Memling, Matsys, Bouts, Ysenbrandt, Afonso and Bermejo—or their followers. One intriguing theory is that it is the work of Lázaro di Andrade, a Portuguese artist who went to Ethiopia in 1520 and stayed for a number of years.

The Kwer’ata Re’esu could have been given by the Portuguese as early as 1520, when a diplomatic mission arrived in Ethiopia (the artist Andrade was part of this group). In an attempt to encourage Ethiopia to convert from its traditional Orthodox faith, the Portuguese continued periodically to visit the country until the final expulsion of the Jesuits in 1634. There was therefore a period of just over a century when the painting could have arrived.

But the evidence suggests that the Kwer’ata Re’esu probably arrived in the early sixteenth century. First, the Portuguese would have been more likely to have given a newly painted work, rather than an old picture. Second, the fact that the Kwer’ata Re’esu had become a sacred icon by the late seventeenth century suggests that it had already been in the country for many years. By this time the Jesuits had been expelled, and it is difficult to believe that a relatively newly arrived Catholic image would have been revered.

The history of the Kwer’ata Re’esu in Ethiopia has been traced by the Ethiopianist Richard Pankhurst, son of the suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst. He notes that the painting’s first recorded appearance was in 1672 in Gondar, the capital of Emperor Yohannes I. By this time the picture had already assumed a sacred status. The chronicle of his reign records that the Kwer’ata Re’esu, a “picture of Our Lord Jesus Christ”, was taken into battle in the south of the country. It was later carried by the imperial forces during other wars and assumed the role of a palladium—an object that ensures the safety of its owners. During a rebellion in 1705 the citizens of Gondar took an oath on the picture.

In 1744 the painting was captured in a battle with Sudanese Muslims, but it was later returned after payment of a ransom. James Bruce, a British visitor to Ethiopia in 1768-73, later recorded in an account of his stay that the “quarat rasou” and other holy relics had been “only a little profaned by the bloody hands of the Moors”, and “all Gondar was drunk with joy” on their return. Bruce went on to describe the painting as “a relict of the most precious kind, believed to have come from Jerusalem”. It was “a picture of Christ’s head crowned with thorns, said to be painted by St Luke, which, upon occasions of the utmost importance, is brought out and carried with the army, especially in a war with Mahometans and Pagans.”

Other evidence of the importance of the Kwer’ata Re’esu is that it was widely copied from the early 1700s in Ethiopian manuscripts and altarpieces. In many of these early copies, the image is surrounded by a red border, and this suggests that it was already encased in the Italian silk.

The Kwer’ata Re’esu became increasingly revered and in 1700 a special tent was allocated to protect the painting in the emperor’s camp. Soon afterwards, a fire swept through the camp, but according to legend it subsided as soon as it reached the tent with the painting. In 1855 the newly crowned Theodorus took the Kwer’ata Re’esu on his first military expedition.

Looting at Maqdala

Theodorus, who felt threatened by the Turks, sought British support and in 1862 he wrote to Queen Victoria to propose an exchange of embassies. The queen did not reply and the emperor then angrily detained the British consul and other Europeans. Protracted negotiations for the release of the hostages broke down and early in 1868 Britain dispatched a military expedition under Napier. At Maqdala, the emperor’s troops proved to be no match for European weaponry.

On 13 April 1868, as the British stormed into Maqdala, Theodorus shot himself. Just after 4pm, he told his servants, “I shall never fall into the hands of the enemy.” The emperor put a pistol in his mouth, fired, and just minutes later his body was discovered by British troops. Beside him lay the pistol, inscribed as a gift from Queen Victoria to Theodorus in 1854, “as a slight token of her gratitude.”

Accompanying the British expedition was Richard Holmes, an archaeologist dispatched by the British Museum. Having succeeded his father as Assistant Keeper of Manuscripts in 1854, his task was to gather manuscripts and antiquities for the museum. Holmes’s involvement is graphically described in letters which he sent back to the British Museum. Three days after the fall of Maqdala, he wrote about being “under fire” as he entered the gates of Maqdala with Napier. “I knew I must be in at once or many things might disappear”, he explained.

Holmes must have reached up and taken the painting from the above the bed of the dead emperor. With other looters on the prowl, he presumably hid the Kwer’ata Re’esu in a bag or under his coat

Holmes was one of the first to reach the emperor’s private quarters, arriving at the bedroom just as troops were identifying the corpse. Holmes later explained in a letter to the British Museum: “I stopped by the body for a few minutes to sketch the features of our dead enemy.” This drawing, done when the body was presumably still warm, survives. On it is a similar inscription to that on the back of the Kwer’ata Re’esu.

Holmes must have reached up and taken the painting from the above the bed of the dead emperor. With other looters on the prowl, he presumably hid the Kwer’ata Re’esu in a bag or under his coat before starting to sketch. The newly transcribed inscription on the reverse of the Kwer’ata Re’esu is crucial evidence about how it was acquired. 13 April was the date of the storming of Maqdala, not of the expedition’s auction of the spoils on 20-21 April. This proves that Holmes personally took the picture, rather than buying it at the auction where he purchased many of the antiquities acquired for the British Museum.

He then set off for London with his booty: nearly 400 manuscripts, the emperor’s gold chalice and crown, other antiquities—and the Kwer’ata Re’esu. After his return, the British Museum presented Holmes with a bonus of £200 “in recognition of the public spirit with which he undertook, and of the services which he rendered to the Trustees in carrying out the archeological expedition to Abyssinia.”

Our extensive search of the British Museum archives has failed to reveal any references to the Kwer’ata Re’esu, although there is documentation regarding Holmes’s other acquisitions bought at an auction of the Magdala spoils. Taking the picture as personal property was a dubious act for a museum keeper dispatched on an official mission to collect antiquities. Holmes could not have argued that the British Museum would be an inappropriate home for the Kwer’ata Re’esu, since some of the other antiquities he brought back went to the South Kensington Museum and there would have been nothing to stop the painting being shown at the National Gallery. Holmes must have felt embarrassed about his decision to take the Kwer’ata Re’esu for himself, and for decades he kept its existence a secret.

Disappearance of the Kwer’ata Re’esu

Theodorus was succeeded by Yohannes IV, who made his peace with Britain. On 10 August 1872, six months after his coronation, the emperor wrote to Queen Victoria and her Foreign Secretary, Earl Granville, about the two great losses at Maqdala: the Kwer’ata Re’esu and an ancient book of Ethiopian history, known as The glory of kings.

In a slightly stilted translation, Yohannes IV told the Foreign Secretary: “And now again I have another thing to explain to you: that there was a Picture called Qurata Rezoo, which is a Picture of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, and was found with many books at Magdala by the English. This Picture King Theodorus took from Gondar to Magdala, and it is now in England; all round the Picture is gold, and the midst of it coloured.” Yohannes IV also asked about the book of laws, concluding: “I pray you will find out who has got this book, and send it to me, for in my country, my people will not obey my orders without it.”

On 29 November 1872 the Foreign Office contacted the British Museum, asking if it knew about the book or the painting, or how they could be traced. In this letter, the Foreign Office official pointed out that preliminary enquiries had already been made about the painting, and “Lord Granville is informed that nothing is known at the British Museum of the Picture.” The book of history, which had been brought back by Holmes, was found at the museum, and a decision was made to return it.

British Museum records show that all efforts to trace the Kwer’ata Re’esu failed. In 1870 Holmes had left the British Museum to become Royal Librarian at Windsor and again he would have been the obvious source of information to help in replying to Yohannes IV’s letter to Queen Victoria. It is difficult to believe he was not approached, but if so he must have denied all knowledge. On 18 December 1872 the Queen replied to Yohannes IV, saying “of the picture we can discover no trace whatsoever, and we do not think it can have been brought to England".

Holmes continued to keep silent about the Kwer’ata Re’esu, despite his close links with the art world. When the first brief details of the picture were eventually published, they appeared in a journal not widely read in Britain or indeed in the art world: in 1895 Le Congo Illustré published an article by Alphonse-Jules Wauters, the Belgian specialist on Netherlandish painting.

The Kwer’ata Re’esu remained a secret to most art historians until 1905, the year before Holmes’s retirement as Royal Librarian. The May issue of the Burlington carried a short anonymous article on “A Flemish picture from Abyssinia”, probably written either by Holmes, who was on the magazine’s consultative committee, or his nephew Charles John—the future director of the National Gallery—who was the co-editor.

The two sales

Holmes, who was knighted in 1905, died in 1911. Six years later the Kwer’ata Re’esu briefly surfaced at Christie’s. Although not identified, the vendor was his widow, Evelyn, Lady Holmes, and the sale was arranged by his brother Charles. On 14 December 1917 the “Bruges School” painting went for £420, going to Martin Reid, of Wimbledon. Throughout the inter-war period Reid kept his ownership of the painting a secret.

After Reid’s death, his heir J.W. Reid sold the picture anonymously at Christie’s on 17 February 1950. It was simply entitled A Man of Sorrows by A. Ysenbrandt. There was no reference to its historical importance, and the provenance was given in small print as simply: “King Theodore of Abyssinia 1868/Sir Richard Holmes KCVO.” No efforts seem to have been made to alert Haile Selassie’s government, and one wonders if Christie’s might have been trying to minimise the picture’s historical significance in order to avoid any legal claims from Ethiopia.

But if Christie’s was underplaying the Ethiopian connection, a senior member of the Royal Library had spotted its significance and took decisive action. Aydua Scott-Elliott, Keeper of Prints of Drawings, alerted an Ethiopian diplomat in London, Ato Abbebe Retta, to the sale. But the authorities in Addis Ababa did not move fast enough, and a government decision to try to buy the Kwer’ata Re’esu only reached London three weeks after the auction.

At the 1950 auction the highest bid was £131, but the painting was bought in and was quickly sold privately to a London dealer acting on behalf of a Portuguese buyer

Miss Scott-Elliott presumably realised that the Ethiopian embassy in London would find it difficult to secure authorisation quickly enough, and she put in a personal bid. She instructed Colnaghi’s to buy on her behalf, but her bid (a sum of under £100) failed to secure the picture. In later years she regretted that the Kwer’ata Re’esu went elsewhere, and in 1961, in answer to a letter of enquiry about the picture, she replied on Royal Library notepaper from Windsor: “There is no doubt that it would be a good thing if it could find its way back to Ethiopia!” Last month we spoke to Miss Scott-Elliott, now eighty-eight, and she still remembers the sale. “The Kwer’ata Re’esu was a unique object and the Ethiopians should really have tried to secure it. But their bureaucracy was rather slow”, she explained.

At the 1950 auction the highest bid was £131, but the painting was bought in and was quickly sold privately to a London dealer acting on behalf of a Portuguese buyer. The price is believed to have been around £300. The anonymous buyer was Luiz Reis Santos, an art historian who had himself published an article on the Kwer’ata Re’esu in the July 1941 issue of the Burlington, arguing that it was not Flemish, but by a Portuguese painter.

Since the painting’s second brief reappearance at Christie’s, there have been several secret efforts to send the Kwer’ata Re’esu back to Ethiopia as a goodwill gesture. In 1961 Sir Denis Wright, then British Ambassador in Addis Ababa, inquired whether the picture could be acquired, but his approaches came to nothing. Santos was a personal friend of the Portuguese Prime Minister, António de Oliveira Salazar, and in 1965 the art historian suggested that the Kwer’ata Re’esu should be bought by the government to present to Haile Selassie, who was coming on a State visit to Lisbon. The Portuguese government never took up his offer, possibly because of the price demanded. Santos died in 1967 and the current owner wishes to remain anonymous.

Two years ago the British Ambassador in Addis Ababa revived the idea of trying to bring the Kwer’ata Re’esu back to Ethiopia, this time to celebrate the centenary of the establishment of the embassy in Addis Ababa. Although its regal significance had expired with the fall of Emperor Haile Selassie in 1974, the painting was still regarded as being of enormous national importance.

No doubt its rediscovery in Portugal will spark off further efforts to recover the Kwer’ata Re’esu. The Ethiopians will find it difficult to put up a strong legal argument for ownership, but on historical grounds, Ethiopia could hardly have a more powerful case for trying to reacquire the picture.