Tracey Emin is internationally renowned for her coruscatingly confessional art, which for over three decades has chronicled an often tumultuous life in various media, including painting, video, textiles, neon, writing, sculpture and installation. Born in Croydon, London, and raised in the seaside town of Margate, Emin first attracted widespread attention when, as a Turner Prize nominee in 1999, she exhibited the now notorious work My Bed (1998) provoking fierce critical debate on what art could—or should—be. Since then, her steadfast refusal to separate the intimately personal from the public has raised her profile to celebrity status as well as making her one of the UK’s most established artists.

In 2007 Emin represented Britain at the Venice Biennale and was also elected a Royal Academician. She received a CBE for services to the arts in 2012, followed by a damehood in 2024. Throughout, she has continued to challenge notions around artistic acceptability and to confront personal trauma, most recently when she was diagnosed with bladder cancer in 2020 and subjected to invasive surgery, all of which is addressed in her work.

Now, Tate Modern is staging her largest retrospective, which will span works from her first solo exhibition at White Cube in 1993 to her most recent paintings, as well as premiering a documentary featuring the stoma bag that she lives with.

The Art Newspaper: Why have you called your Tate Modern exhibition A Second Life?

TRACEY EMIN: For a long time there wasn’t a title, and it was only when I came up with A Second Life that we could really curate the show. We kept saying things like “old work, new work, before and after”, and I realised that the really big “before and after” in my life is before cancer and after cancer. My life changed so dramatically since my cancer: it is just so much better, so much happier, so much more fulfilling. I keep saying to myself, if I had a choice and knew what was going to happen, would I have gone for the cancer and have this wonderful, amazing life that I have? Even when I’m sad or unhappy, I’m never as sad or as unhappy as I was before—I can rectify it, I can put it right.

Having had this edge of nihilism always throughout my life, even as a child, then facing this wall of death like I did, and thinking, is this what I want?, I knew, no, it’s not what I want, I want to live! And if I want to live, what’s the point of living unless it’s worthwhile, unless you do something?

You have certainly achieved an astonishing amount over the past five years. As well as all the work you have made, you have moved permanently back to Margate and established the Tracey Emin Artist Residency, a free studio-based art school, along with many other initiatives in the town.

I’ve done more in my last five years than in the whole rest of my life. But I didn’t set out thinking, oh, if I survive this, I’ll open an art school and create an amazing art world in the town where I grew up. That all just came afterwards with the joy of living. It’s like I’ve been given a second chance. There was six months to live, and then it’s like someone said, “You know what? I don’t think she’s all bad. Let’s just give her one more chance to see what happens!” And it’s paid off.

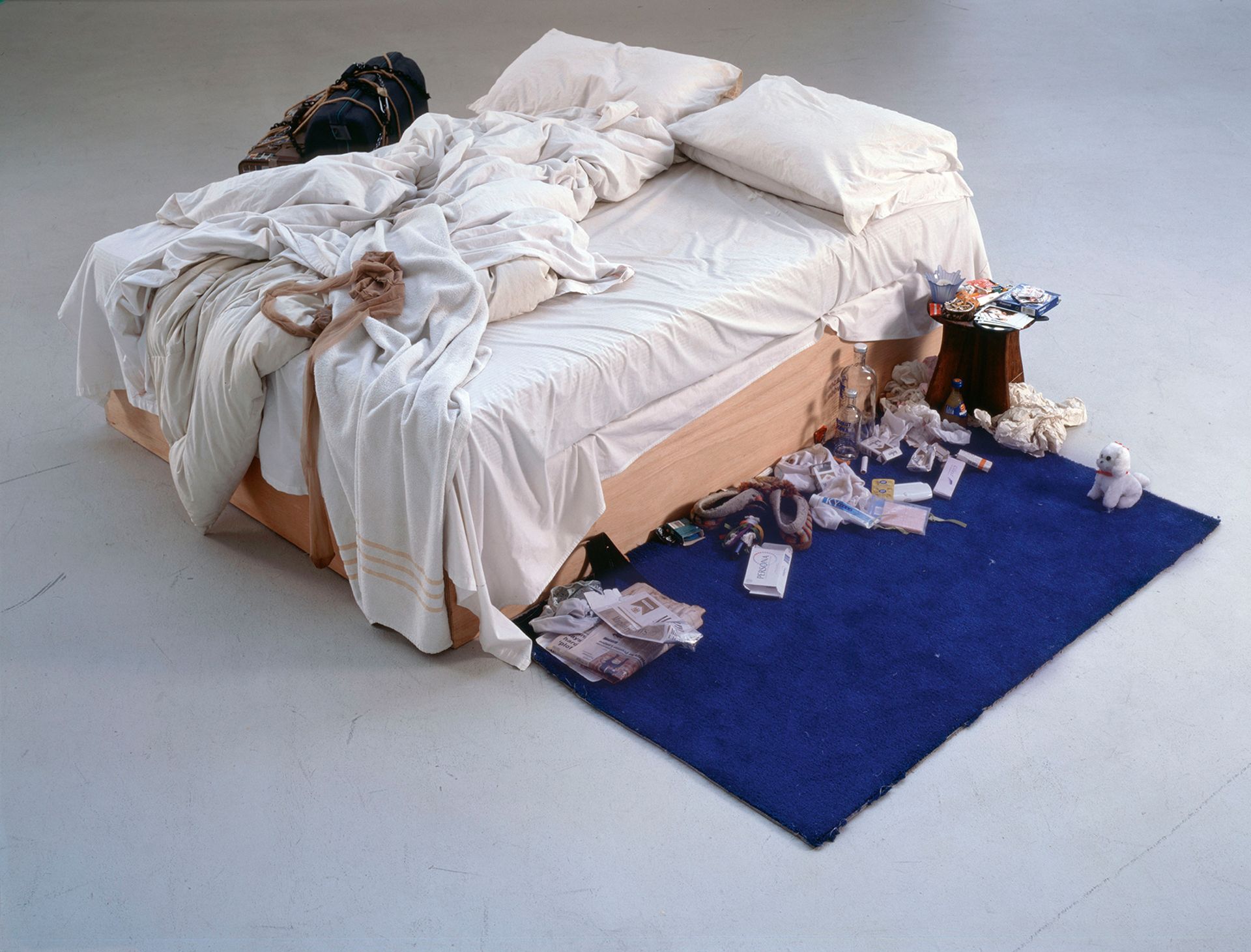

In her Turner Prize-nominated installation My Bed (1998), Emin’s squalid depiction of the depression that descended as a result of relationship breakdown sparked public controversy and made her a household name Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates, courtesy Saatchi Gallery

How does it feel seeing all these works from your different lives coming back together again?

The show isn’t strictly hung chronologically. It’s more complex. We’ve got these categories like Margate, Cyprus, Youth, Rape, Abortion, Mother, Father. So in the Margate bit, I have a painting that I did last year, and the bed [My Bed, 1998] is actually in the second half, because it’s another affirmation of a different kind of near death, more mental than physical (although I was also incredibly thin, I weighed around seven stone when I made it).

Curating a big show like this is like curating a show by many people because I work in all these different mediums: we’ve got video, films, photos, all kinds of stuff mixed in with painting and drawing and sculpture, and it will be interesting to see really old works hanging next to new works.

You have an incredible range. But while your media may change, your core preoccupations have been in place from the word go.

Yes, even at art school when we did life drawing, I’d make the figure look like me. Or when we had a project to draw something from the home, I’d draw pictures with me naked in the mirror, drinking tea, looking really sad. If we had to draw buildings, I’d go and draw the house that I lived in as a child. But when I was younger, people just thought it was narcissistic.

Even my first show at White Cube [My Major Retrospective, 1993], people thought that I’d made it up. But I hadn’t, it was all really sincere. It was real. I think I came about at a time when the art world wasn’t looking for sincerity, it was looking for a sort of brashness. And it wasn’t looking for the hand touch. I think that’s why me and Sarah [Lucas] united—because we were interested in things that we’d touched, that were obviously handmade and not necessarily well made. It’s more like a compulsion to create, that’s what’s driven me—the need to be hands-on with everything and touching things.

In her bronze sculpture Ascension (2024), Emin explores her relationship with her body following major surgery for bladder cancer in 2020, from which she received the all-clear four years later Photo © Theo Christelis/White Cube

This love of making has certainly endured, even your giant bronzes carry your fingerprints.

A lot of people when they go to my Tate show—and especially young people that haven't seen the bed, haven't ever seen the blankets—they'll see that these things are really made. I didn't hand them out, they’re not fabricated. Everything I do in my studio now it's just me, and Harry [Weller, creative director of the Tracey Emin Studio] occasionally comes in. I don't have any assistants. If I don't feel like working, there is no work—it’s that simple. I think now is a time where I can be more appreciated for what I do as an artist, not just for what the work is about, but also how I go about it.

From the very beginning of your career, you have made work about things that people did not want to talk about—and often still don’t—such as growing up in poverty and being mixed race (something that until recently has largely been glossed over).

This to me is quite shocking because even in my Hayward show [Love is What You Want, 2011] there was a whole room called Menphis [sic] that was all about Cyprus and my Nubian great-great-grandfather and not once was it even mentioned. I’ve never made a song and dance about it. I make work about my background and being Cypriot and the Nubian thing and all of that, which is just part of me. [Being brought up by a] single parent, leaving school at 13, leaving home at 15—all of these things are quite loaded, and the expectations of me were obviously not very high. So I’m a good role model for showing what is possible if people are given a chance to excel and do what they’re good at. And be told that they’re good at it, too, which is important.

Recently you have been making a lot of paintings, but your relationship with paint has been a complicated one. The Tate show will include photographs of the works you destroyed when you abandoned painting in 1990—the year after you finished your MA at the Royal College of Art (RCA)—as well as your subsequent attempt to reconcile yourself with painting in the 1996 installation Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made.

No matter what problems I had personally at the RCA, it was brilliant and I learned so much while I was there. When I left the RCA and I was pregnant and I was homeless and I had all this stuff stacked up against me, I just thought, fuck it—I’ve done all this and still there’s no life for me, I’m still at rock bottom. I felt like a failure, and it deeply affected me. It was terrible. I realised after being pregnant that I didn’t want to make pictures. I had to make the essence of art, of what is really meaningful. I had to make art for the truest, purest reasons, and it had to be really extraordinary, otherwise I couldn’t justify what I was doing.

Then I did a philosophy course, which really helped my mind untangle things. With the writing, I started thinking conceptually, making ideas. And with that you don’t need anything, you just need a pen and paper, so I could get my mind working and be creative. And then I started painting again in 1999.

Tracey Emin’s The End of Love (2024): ”When I go in to paint on the canvas, I have absolutely no idea what’s going to happen. I think that’s also why I stopped painting—I was scared of it, like I was going to be consumed by it all”

Photo © Ollie Harrop

Can you talk about the act of painting? It seems that increasingly you have been using the physical stuff of paint to take you in different directions, into a state of flux and flow, with your paintings evolving in a kind of process you have described as alchemical and mediumistic.

Totally. And now it’s even more extreme. When I go in to paint on the canvas, I have absolutely no idea what’s going to happen. I think that’s also why I stopped painting—because I was scared of it, like I was going to disappear or be consumed by it all. It’s taken me a long time to overcome this and understand that a canvas is like a kind of mirror or a wall that I can walk towards, and I can go through it and come back out again. It’s like an entity, a thing.

So now I get myself ready for painting, and I go into the journey because I know something’s going to happen to me. It’s like having sex with someone new that you really love: you’re never going to be the same again, never going to be the same person afterwards. It’s like that every time I start a new body of work, [I get into] a new headspace with painting. I won’t paint for the sake of it. I’m not one of these 9 to 5 people. I never work towards a show. I just work, work, work.

There are also many figurative bronzes in the show, both tiny and massive.

I’ve been making bronzes forever, but the large figurative ones only since 2016, when I took a year’s sabbatical and learned how to make my first giant bronze. I got so much help from the people at the Louise Bourgeois foundation, working at the New York foundry. It really was amazing for me. Before I became friends with Louise, I just made really tiny bronzes. But Louise’s sense of scale was colossal, and that really inspired me: a tiny woman making giant things. She just made what she wanted to make, and it was fantastic how she took the challenge of all these different materials.

Even when they are huge, your bronzes subvert notions of monumentality. The colossal The Mother (2022) outside the Munch museum in Oslo seems more nurturing than oppressive. Then there are the doors you made for the National Portrait Gallery (NPG), which are incised with faces of women, including your mother. Or the painted bronze baby clothes you installed in public spaces throughout Folkestone in 2008—you can’t get more unmonumental than a knitted bootie.

But the idea isn’t unmonumental, the idea of these tiny little baby clothes that have been lost is really big. The idea came about because in Folkestone, as well as in Margate, there are a lot of single mothers, and I wanted to pay tribute. I wanted people to think about all of those young women, and what it means and how badly they are often treated. With the NPG doors, I like their simplicity and that people can take them or leave them, they can just walk through, but if they look there’s also something else. The Mother in Oslo is more primal, she’s protecting everyone, she’s protecting Munch. The reason why I never wanted to work with large public sculptures is because they were so masculine and macho and I didn’t want to be part of that tradition, I wanted to do my own thing. And now I’ve found a way of doing it—but it just took the balance of time.

You are no longer Mad Tracey from Margate, which is the title of one of your 1990s appliqué blankets. You’re now Dame Tracey Emin, DBE, RA, Honorary Freewoman of Margate. What advice would you give to your younger self?

There are many things I would say that wouldn’t be particularly kind or nice. But I would also say exactly what’s happened: don’t give up, never give up.

• Tracey Emin: A Second Life, Tate Modern, 27 February-31 August

Biography

Born: 1963 Croydon

Lives and works: Margate and the south of France

Education: 1986 Maidstone College of Art, BA; 1989 Royal College of Art, MA

Key shows: 1997 South London Gallery; 2003 Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam; 2007 British Pavilion, Venice Biennale; 2011 Hayward Gallery, London; 2020 Royal Academy of Arts, London; 2025 Palazzo Strozzi, Florence

Represented by: White Cube, Galleria Lorcan O’Neill Roma and Xavier Hufkens