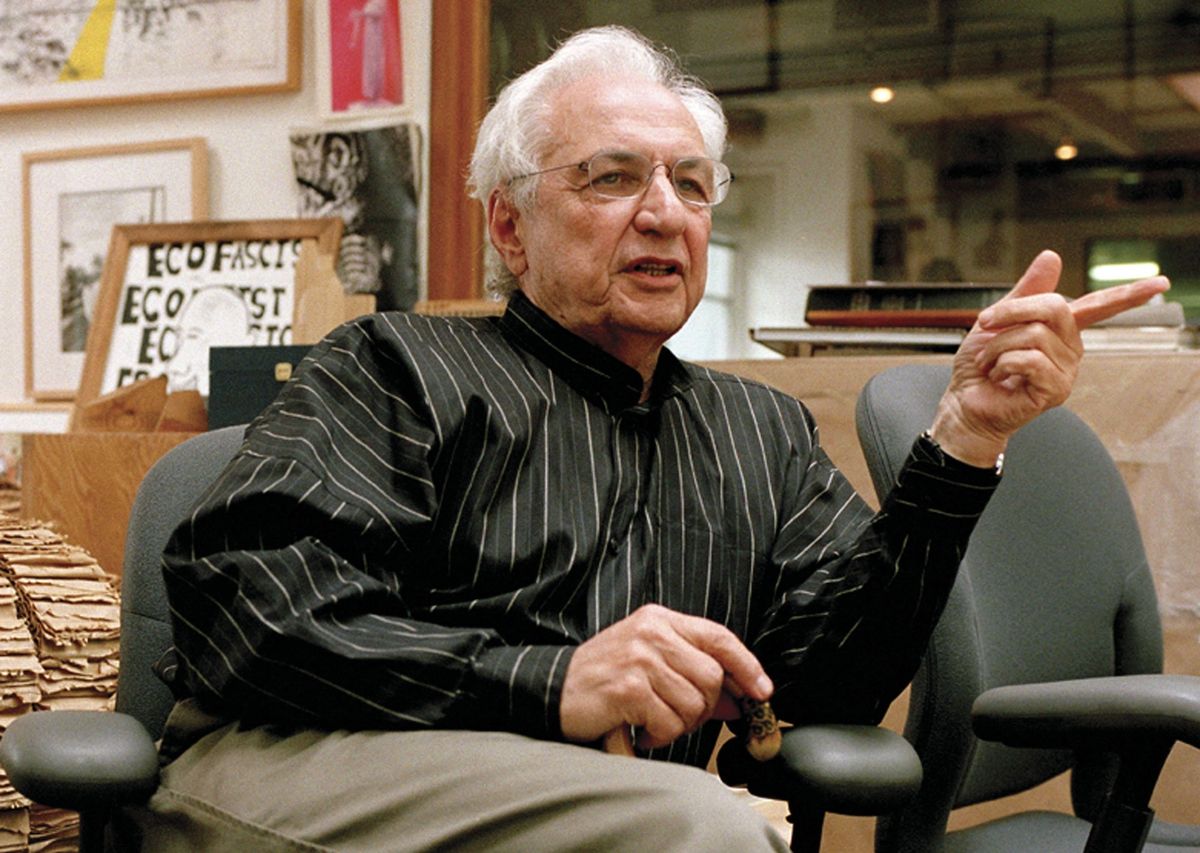

For decades Frank Gehry (1929-2025) liked to discuss his architecture in terms of sculpture, recognising that he was at some level in the business of creating volumes of matter, light and space. Then, as he grew world-famous for dramatically formed or deformed buildings—The Simpsons joked that he crumpled a letter from Marge to come up with the design for a concert hall—he would cantankerously push back on that notion. In his later years, he would insist that his buildings were not so close to sculpture after all.

But throughout his career, one thing was clear: Gehry was always an artist’s architect, to an extent not recognised by his many obituaries. He was lifelong friends with numerous artists; he designed exhibitions for them and, most famously, he built museums catering to their needs as much as to the demands of his billionaire clients.

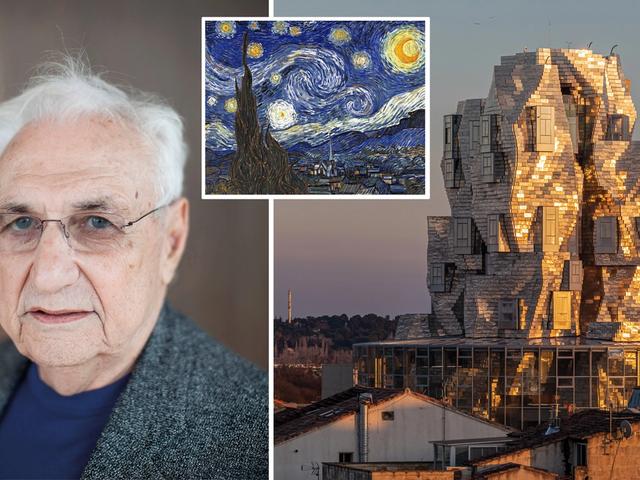

His most exuberant, dynamic buildings are art museums: the Museo Guggenheim Bilbao, finished in 1997, and the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, done in 2014. With Bilbao, he established a signature look: a titanium-clad building on the riverfront where the walls billow like sails full of wind. A frequent sailor, he took this aesthetic even farther in some ways in Paris, with an ethereal, curved-glass structure that he compared to a full regatta.

The Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris Photo by Jacqueline Poggi, via Flickr

When it comes to displaying art, Bilbao with its irregular floorplan poses some of the same practical challenges as Frank Lloyd Wright’s dizzying Guggenheim Museum in New York. But Gehry believed he was giving artists what they really wanted: a strong alternative to the white cube. “I’ve been listening to artists for 40 years about what galleries they want. Every artist I know loved Bilbao,” he told The Art Newspaper in 2014. “Every museum director I know hated Bilbao.”

Gehry also renovated several art museums with great success, whether adapting—with a remarkably light touch—a vast police car warehouse in 1983 for use as a branch of Los Angeles’s Museum of Contemporary Art (Moca), now called the Geffen, or overseeing the recent renovation of the Philadelphia Art Museum by carving out new spaces underground and refining visitor flow throughout. (His contribution to Moca was so subtle that he once referred to himself as “a janitor”.)

Historically, art opened the door to architecture for him. In the late 1940s, before studying architecture at the University of Southern California, he took a ceramics course there with Glen Lukens, known for fusing rough surfaces with experimental but elegant glazes. Lukens lived in Los Angeles in a low-slung, Bauhaus-inflected masterpiece by Raphael Soriano and Gehry’s visit to the site was, he said, “a lightbulb moment” when he realised he was more interested in making buildings than pots. Or, he sometimes joked, Lukens nudged him along, telling him he would never make it as an artist.

In the 1960s and 70s when building his own architectural firm, he was close to many Los Angeles artists, including Billy Al Bengston, Larry Bell, Tony Berlant, Robert Irwin, John Altoon, Peter Alexander, Charles Arnoldi, Ed Moses and Ed Ruscha. As several of them began using industrial materials like fiberglass and plastic to make art, Gehry began using chain-link fencing and corrugated galvanised steel as a building material for the career-defining expansion of his own Santa Monica home, originally a Dutch Colonial-style bungalow, in the late 1970s.

The Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis Photo by McGhiever, via Wikimedia Commons

“These artists are all my friends,” Gehry told me in 2005, when the group show West! Frank Gehry and the Artists of Venice Beach opened in Minneapolis at his Weisman Art Museum, a proto-Bilbao structure. “They supported me before anyone else did, and they ignited my imagination in ways that architecture didn’t at the time.”

He credited these artists with sparking some ideas for his laboratory of a home in Santa Monica, telling the journalist Barbara Isenberg that he was especially moved by the rawness of their studios. Bell, for instance, had a studio on Market Street in Venice where he left a large hole in the wall. “I loved that you saw the studs inside, were looking at the wood studs as if they were a picture,” Gehry said, adding that Moses was toying with using corrugated metal for his studio. “I then went on to use the corrugated metal. Maybe I would have gotten there by myself, but Ed sort of energised it.” (Critics have also cited Irwin’s stretched scrims as a point of inspiration for Gehry’s use of chain-link fence.)

The Gehry House in Santa Monica Photo by IK's World Trip, via Flickr

Frank Gehry on LUMA Arles: ‘I kept thinking about what the light was like for Van Gogh’

Ruscha tried describing Gehry’s approach in Sydney Pollock’s documentary, Sketches for Frank Gehry (2006): “He mixes the freewheeling-ness of art with something that is really concrete and unforgiving, which is the laws of physics.”

As shown beautifully in that film, Gehry also shared the artists’ devotion to tinkering with or manipulating materials as a tool for problem-solving. He and his team used pieces of paper and cardboard to make and remake models instead of going directly from drawings to scaled models. He even crafted the same building at different scales so as not to fetishise any one miniature. And he ultimately showed these models at museums, along with various art objects that he devised, like his large fish sculptures and lamps.

His friendships with artists led him to design several museum exhibitions, from a 1968 show of Bengston at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma) to a 2012-13 retrospective of Ken Price at the same museum. The curator there he worked with most closely, Stephanie Barron, also brought him in to design important historic surveys, such as a 1980 show of Russian Constructivism and 1997’s Exiles and Emigres: The Flight of European Artists from Hitler.

The Price exhibition was particularly stunning, thanks in no small part to the series of overhangs, display cases, pedestals and shelves designed by Gehry. As a collector of Price’s work, he knew just what it needed to shine. The architect in effect created geometric niches for the artist’s iridescently coloured, biomorphically shaped or oozing-extruding ceramics that gave them a visceral immediacy, setting off their every weird bulge.

Installation photograph, Ken Price Sculpture: A Retrospective, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 16 September 2012-6 January 2013 © Estate of Ken Price, photo © Fredrik Nilsen

By that time, Gehry was celebrated internationally as a starchitect, which brought sniping from some critics and clients about his aesthetic ambitions trumping budget constraints or practical priorities. Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles was a magnet for controversy, and lawsuits over cost overruns ensued. The mega-donor Eli Broad even tried to fire Gehry from the project in what must have felt like déjà vu for all—Broad previously had hired Gehry to design his home in Brentwood until, exasperated by delays, he took the drawings to other architects to complete. (Gehry disowned the resulting home.) And after Disney Hall opened in 2003, a success in so many ways, it turned out the exterior stainless-steel panels were overheating the city block.

No wonder Gehry pushed back in recent years on people viewing his architecture as a form of art. He instead trumpeted the fact that his firm helped to develop the sophisticated computer-modelling programmes needed to realise complex, non-rectilinear buildings. He insisted, even if it was not always true, that his projects came in on budget. And his buildings must be judged for how they function and stand up over time, not just their adventurous forms.

In that sense, sure, we can all respect Gehry’s late-in-life claims that his buildings were not sculptures. We all know there are big differences in the basic objectives, standards for evaluation, regulatory practices and, yes, plumbing between the fields of art and architecture. And yet it should also be said: Gehry was an artist all along.