The paintings of the German artist Max Beckmann are easy to recognise but hard to categorise. Often mislabelled as an Expressionist or else vaunted—to his chagrin—as a leading figure of the Weimar era’s New Objectivity movement, Beckmann (1884-1950) was a singular, wilful figure, with a sharp but ethereal palette and a crowd of recurring figures that included circus characters, street toughs and his own menacing, mask-like face.

However, an exhibition opening this month at Frankfurt’s Städel Museum stresses the importance of Beckmann not as a painter but as a draughtsman. The show, Beckmann, is a rarity for the artist, focusing solely on his drawing in 80 works, including loans from major collections on both sides of the Atlantic.

The exhibition is curated by Regina Freyberger, Stephan von Wiese and Hedda Finke. (This month, the latter two are publishing the first two parts of their three-volume catalogue raisonné of Beckmann’s drawings.) The show will begin in the decade before the First World War, when Beckmann was shaking off the residue of German Impressionism and absorbing the impact of French Post-Impressionism; an early, soft-featured self-portrait from 1912, rendered in pencil, could be from the late 19th century.

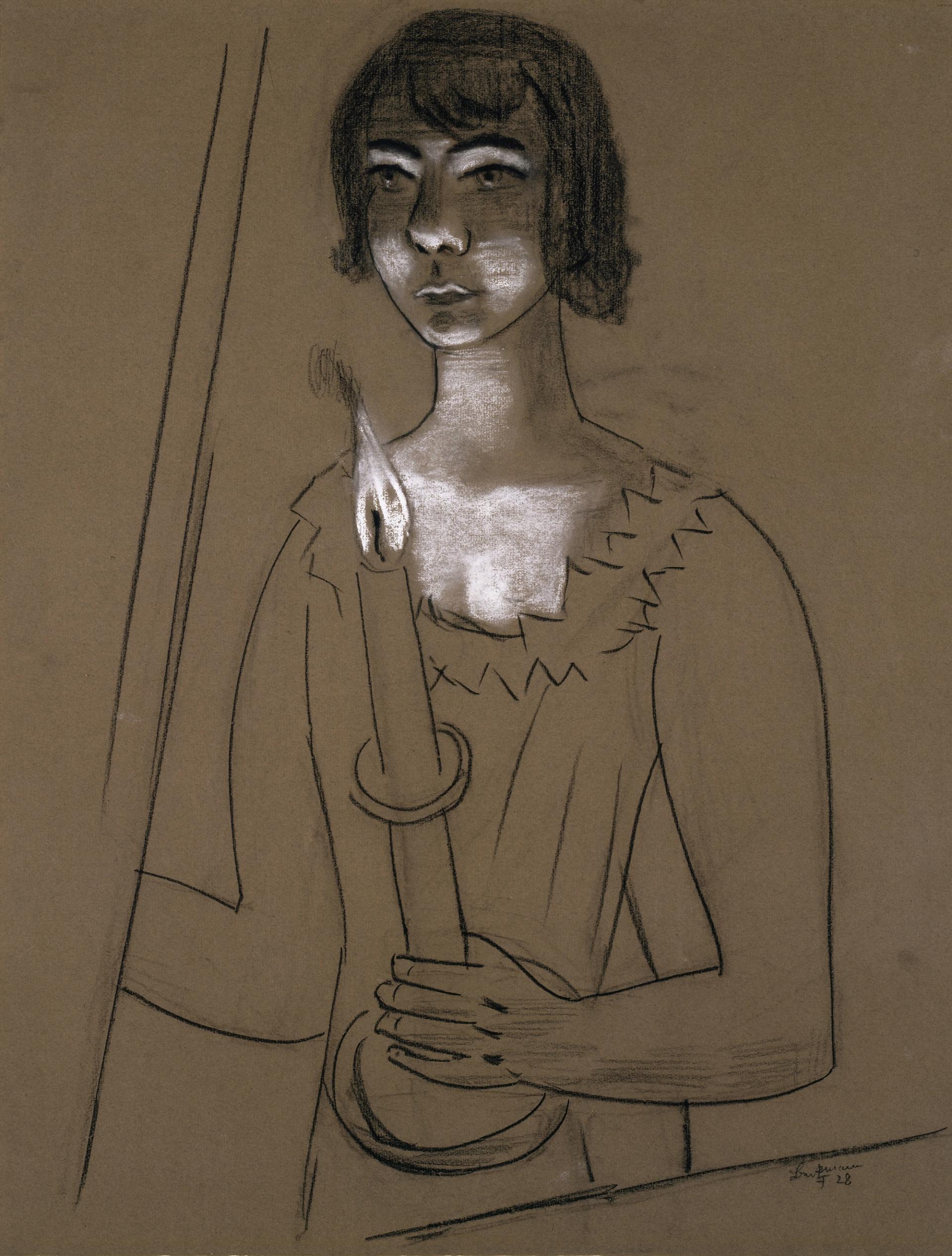

Max Beckmann's Woman with Candle (Quappi) (1928) Kunstmuseum Basel, Kupferstichkabinett; Photo: Kunstmuseum Basel

The war strongly affected Beckmann, with his experience as a medic leading to an apparent breakdown in 1915. But the conflict also made him a major artist by wholly reconfiguring his art. His hard-edged signature style first emerged in his drawing, Freyberger says, and coincided with a new approach to drawings generally, which by the 1920s had gone from painting studies to autonomous works of art.

In 1925, Beckmann divorced his first wife, the opera singer Minna Tube, and married the Bavarian-born Mathilde “Quappi” von Kaulbach, who became his lasting muse. In a 1928 drawing of Quappi holding a candle, the artist vividly captures the effect of light on her face and chest by using little more than chalk and pencil on cardboard.

After the Nazis came to power, Beckmann was fired from his prestigious teaching post at Frankfurt’s art academy, leading to his Dutch exile in 1937. The existential threat of the 1930s brought colour into his drawing, and The Murder (1933), from the Städel’s own important collection, uses watercolour and gouache over charcoal to depict a tumultuous crime scene in eerie pastels.

Max Beckmann's The Murder (1933) Städel Museum, Dauerleihgabe aus der Sammlung Karin & Rüdiger Volhard; Photo: Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

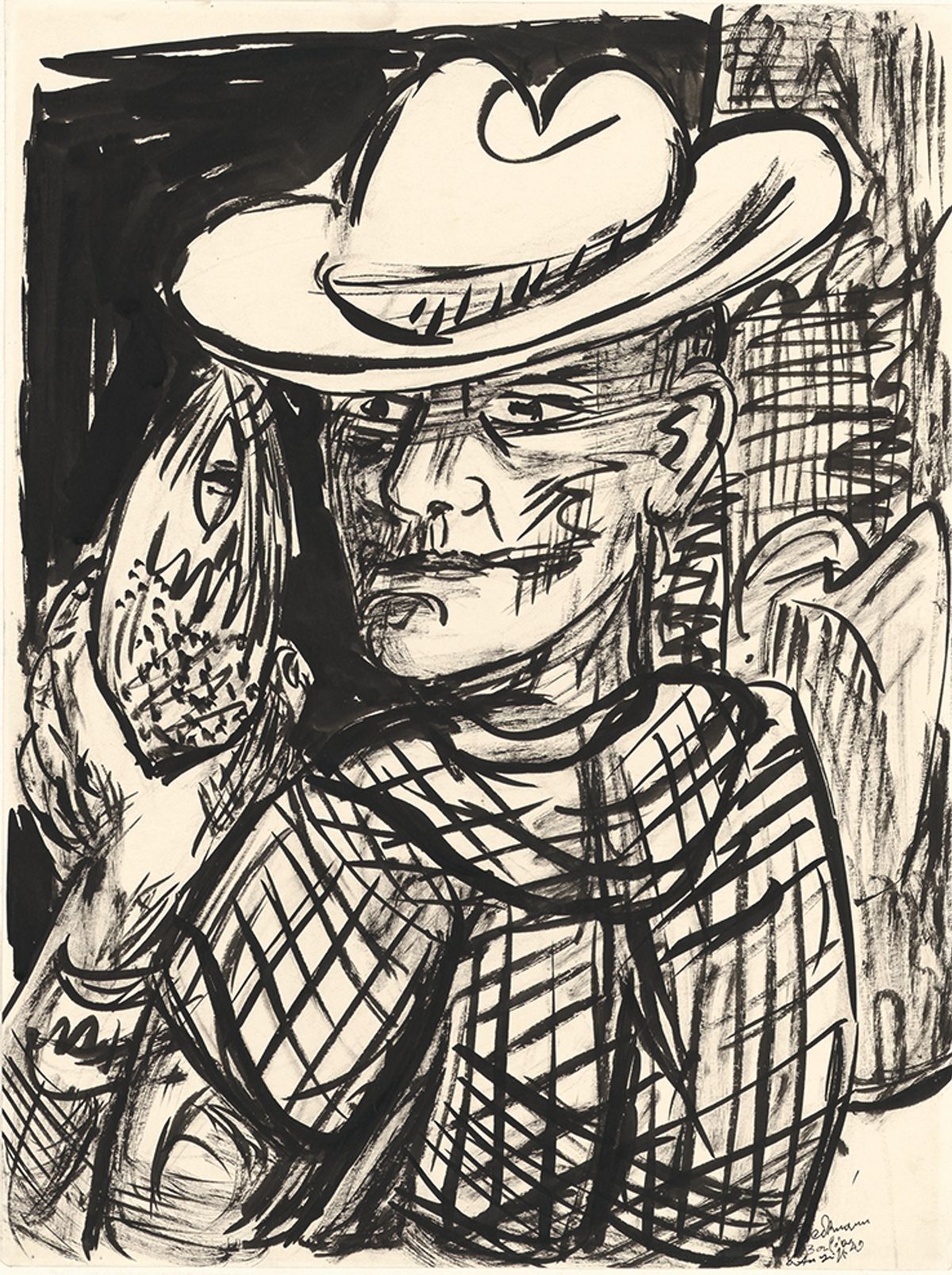

The exhibition will be rich in works from the last decade of Beckmann’s life, starting with the pitch-dark war years cooped up in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam, followed by a restless but rousing post-war turn in the US. Two works from 1949, completed in Colorado, reveal the artist’s ambivalence towards the rawness and weirdness of the New World. In Rodeo, a cowboy tossed into the air is a dire reimagining of a circus figure, while in a very late self-portrait Beckmann adopts an all-American cowboy hat—but holds up an Old World emblem, in the form of a fish.

• Beckmann, Städel Museum, Frankfurt, 3 December-15 March 2026