New Gold Standard

“Decode it to recode it”, said the show notes for Jonathan Anderson’s first collection for Dior, a show that was the much-anticipated unveiling of the 41-year-old Northern Irish designer’s vision for the house that is the jewel in the crown of luxury goods behemoth Louis Vuitton Moët Hennesssy (LVMH).

His menswear collection for spring/summer 2026, presented on 27 June in a bespoke marquee in front of the Hôtel des Invalides in Paris, where the Emperor Napoleon is entombed in conspicuous splendour, was a sure-footed tour de force—not just in the fashion house’s own history but across centuries of men’s dressing. In 67 looks, Anderson’s mantra was brought to life.

Adroitly reworking classic Dior women’s silhouettes, he remixed the famous Bar jacket (a linchpin of Christian Dior’s own inaugural New Look couture collection of 1947) into curvaceous blazers cut from finest Donegal tweed. The elaborately folded skirts of 1948’s Delft evening dress mutated into knee-length cargo shorts billowing with metres of undyed denim. The surgically sharp hips of Dior’s La Cigale [cicada] dress of 1952 influenced silhouettes throughout.

Draped in a dreamcoat

There were iterations of men’s fashions, from the British dandy Beau Brummell to Left Bank 1960s student rebels (think sheepskin-trimmed bombers and leather trousers) and 1980s Golden Boys in neckties and underwear. It was all grist to Anderson’s trend-friendly mill.

“Originality is nonexistent,” Anderson declared in a speech while accepting an honorary doctorate from the University for the Creative Arts in London last year. “Steal, adapt, borrow. It doesn’t matter where one takes things from. It’s where one takes them to,” he continued, riffing off the American film director Jim Jarmusch, who in turn was paraphrasing Jean-Luc Godard.

In the case of Look 7, though, it very much mattered. This was an apparently straightforward knee-length, single-breasted coat with notched lapels and flap pockets (reminiscent of Dior Homme by Hedi Slimane, circa 2007). But as the model moved the garment shimmered—its fine houndstooth pattern glimmering with gold thread. Before the show, the head of the atelier pointed out that thousands of the tiny houndstooth motifs (the pattern is another Dior signature) were meticulously aligned down seams and beneath pocket folds. News quickly spread that it took 12 artisans 34 days to fabricate, and the price tag of €200,000 was also disclosed—perhaps the sign of a new era in luxury menswear.

It turned out that the source of the technique harks back centuries to the Awadh region of northern India. Known as mukesh work, it is a unique embroidery technique where fine metallic balda thread is folded and applied on the visible side of woollen fabric, then fixed on the back with aramid thread. The result is extraordinarily luminescent. Draped in this dreamcoat, the model, sporting a stiff, white-satin “stock” collar with an elaborate butterfly bow and a naked torso, stared straight ahead as he marched—Dior trainers flamboyantly unlaced—into the future.

Anderson received a standing ovation.

Stephen Todd

Super Nature

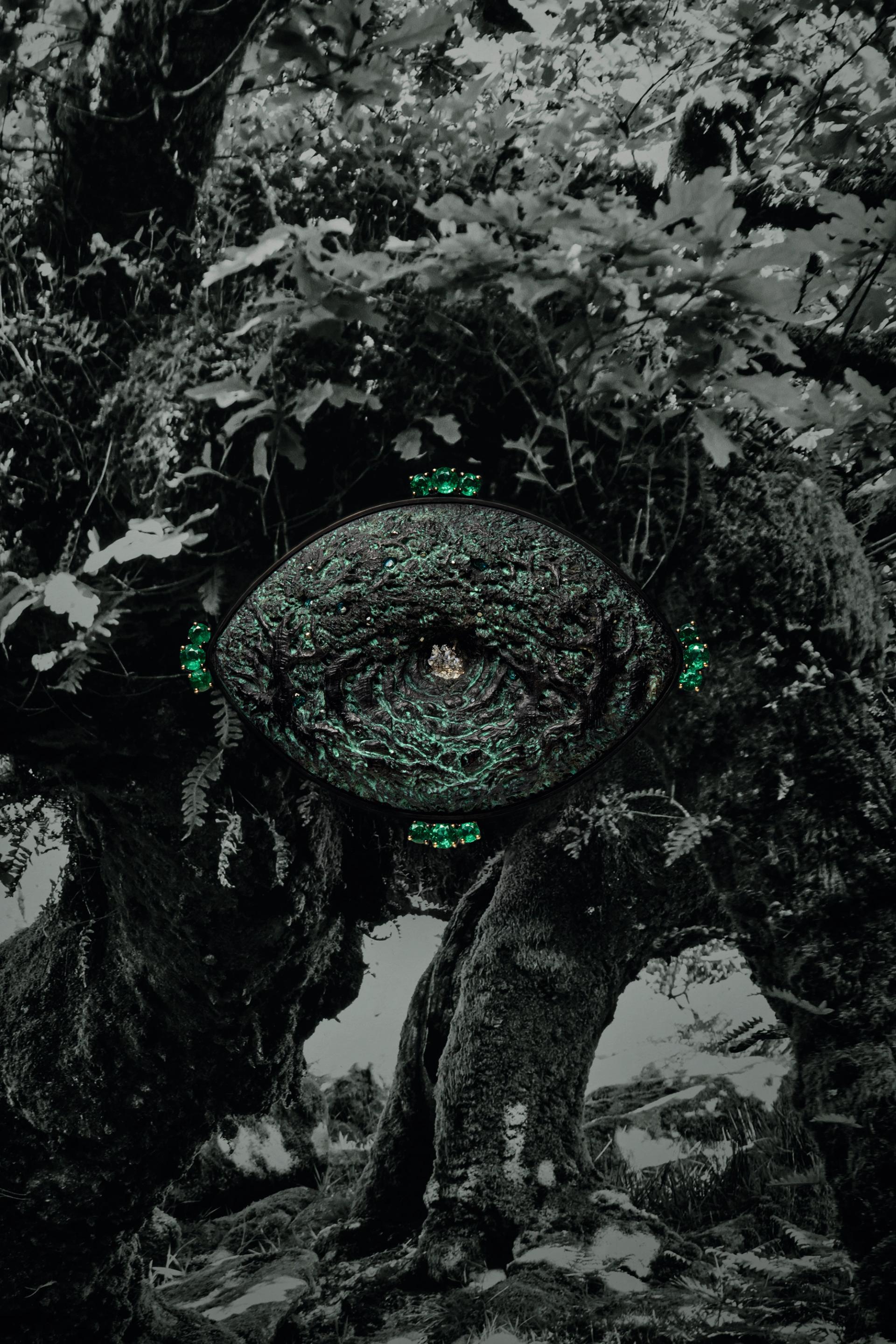

Eye of Nature pendant

Tessa Traeger

At the heart of Natasha Wightman’s new collection of jewellery, on display at Christie’s London from 8-23 October, is an unusual wood: bog oak. Dense, inky black and semi-fossilised in fenland bogs for thousands of years, Wightman describes it as “Britain’s memory in material form”.

The large mandorla-shaped designs she has created celebrate in intricate shallow relief the remaining British temperate rainforests, still standing in small sites from Dartmoor to Snowdonia. Carved in miniature by master carver Graham Heeley from fragments of ancient trees known as the Hemplands Haul—recovered from Norfolk’s Wissington fens—these artworks are then framed by Wightman with precious metals and gems. The emeralds, sapphires and diamonds reflect the environments of forest and coastline that the trees once covered, now denuded by modern farming, urban sprawl or coastal flooding. “These bog oak pieces carry the story of our lost ecosystem,” she says. “You are literally handling Britain’s history.”

Natasha Wightman © Alex Johnson

Wightman hopes to draw attention to the living remnants of this threatened environment not just through the jewellery itself. It has been photographed being worn by young environmental activists Mya-Rose Craig and Erinna Miles to highlight the ongoing battle to study and preserve these habitats, accompanied by lyrical landscape and still-life photography by Tessa Traeger. The Christie’s launch will include an exclusive preview of Lost Forests, a documentary directed by Wightman, with a soundscape and live choreography. “I trained as a dancer,” Wightman says. “Because the pieces are wearable it was important to me that they should be understood through a physical medium as well as a visual one.”

Wightman came upon bog oak by chance. Her first jewellery collection, Ravens, released last year, was inspired by two birds she watched closely in the landscape around her Sussex home. For that project, she searched Britain for artisans who could help realise her designs, in the process creating a small team of specialist goldsmiths and carvers. They are conservators of a different type—of the vanishing tradition of miniature workmanship. Besides the ravens rendered in microscopic detail in 18-carat gold and solid silver, Wightman designed birds that were carved by Heeley from antler, jet and moorland boxwood. “I am always looking for materials that have a story and are indigenous to Britain,” she says.

It was reading campaigner Guy Shrubsole’s 2022 book The Lost Rainforests of Britain that alerted her to bog oak and led her on a journey to revisit Britain’s standing fragments of rainforest—only 27% of which are protected.

Out of these experiences were born the intensely realised miniature landscapes, shimmering with 24 carat shell gold palladium and white gold, that form the Lost Forests collection. Some pieces evoke snow-capped mountains or Dartmoor’s vast skies above a twisted mass of ancient oak branches intertwined with hazel, hawthorn and rowan. Others pursue traces of forest from Cornwall’s sculpted coastline, featuring a particular cove that Wightman has often visited, to Scafell’s secret streams.

Mountain pendant Leo Bieber

A piece that can be worn as a brooch or pendant, called Eye of Nature, is particularly immersive. Dense and intricate carving precisely delineates a tunnel of tangled roots and branches, shimmering with black and teal-tinted diamonds. Among the other pieces are earrings featuring snow-dusted Scots pines and another pair featuring a more abstract pattern of delicate ferns, fringed with emeralds.

The fragility of these precious landscapes is offset in all these artworks by the calm resilience of the bog oak, and the enduring brilliance of the jewels. Wightman’s pieces communicate an urgent story in ways that allow us still to revel in the inherent beauty of these ancient materials.

Emma Crichton-Miller

In miniature

Petronella Oortman’s doll’s house (1686) Courtesy Rijksmuseum

The Rijksmuseum’s curators describe Petronella Oortman’s doll’s house as a work of art. It is on the Amsterdam museum’s list of ten must-see exhibits, with Rembrandt’s The Night Watch, van Gogh’s Self-portrait and Vermeer’s The Kitchen Maid. Oortman’s doll’s house will also play a starring role in At Home in the 17th Century, an exhibition opening this autumn (17 October-11 January 2026).

But what actually is it? Never intended for children’s play, Oortman was 30 in 1686, the earliest date the museum believes it could have come into her possession. As an object, it has the character of a piece of elaborate 18th-century French furniture, its oak frame embellished with a flamboyant tortoiseshell and pewter inlay. There is a handsomely proportioned opening glass front, supported on two groups of four swooping curved volute legs, connected by scalloped X-shaped braces.

Oortman (1656-1716) likely spent two decades and a good deal of her silk merchant husband Johannes Brandt’s money filling her house with exquisitely made miniature furniture. There was running water in the kitchen and 83 tiny leather-bound printed books in the library. She commissioned woodcarvers, basket weavers, silversmiths and glassblowers to work for her. Cornelis Dusart, a genre painter from Haarlem, contributed two miniature canvases that hang on the walls. There are two kitchens: in a telling foreshadowing of the signifiers of contemporary affluence, one is simply for show and has a display cabinet of genuine Chinese porcelain made specially for the house. The other has an oven.

The conviction with which the house has been filled is compelling. Its paintings, books, and even the collection of shells are not representations of objects, they are actual objects.

Popular pursuit

Oortman’s doll’s house was more than a one-off passion. Other Dutch women of her time and class pursued similar projects. The Rijksmuseum has another less elaborate doll’s house in its collection, and the Centraal Museum in Utrecht has one too. They have been interpreted as a female version of the “cabinets of curiosities” assembled by male connoisseurs.

In Britain in the 20th century, the architect Edwin Lutyens designed a doll’s house for Queen Mary, with books specially written for the library by A.A. Milne and Arthur Conan Doyle, and 1/12th scale bottles filled with wine in the cellar. It is on show at Windsor Castle.

Oortman’s doll’s house has inspired the creative imagination of several others. Jacob Appel made the house the subject of an oil painting in 1710, which also hangs in the Rijksmuseum. Three centuries later, the English writer Jessie Burton made Oortman’s doll’s house the centre of her best-selling novel The Miniaturist.

What distinguishes the doll’s house most is the detailed portrayal of affluent life on the Herengracht of its day. Burton told the Bookish website: “What fascinated me was the distance between us and the tiny world of the doll’s house—it reflects us but we can never penetrate it. It shows us things we haven’t seen – it comments both on our power and our powerlessness. It is an interior world of secrets, of hidden consequence, an illusion of closeness, locked away.”

Deyan Sudjic

Let them wear Blahniks

Shoes worn by Marie Antoinette Musée Carnavalet

When the Archduchess Marie Antoinette married the Duc de Berry, Dauphin of France, she was just 14. Her teenage Austrian feet were about size 3 and still growing, but perhaps the dainty pointed shoes that she wore thereafter kept them small, like a geisha’s.

Style was everything at Versailles, and the Dauphine followed fashion and made it too. The cut-away mules that she favoured made no concession to the instep, sliding the foot down into the toe, halfway to a ballerina’s en pointe. Walking in them was slow dancing in them was agony and they were remarkably hard to keep on. One was lost in the mud when she descended from a carriage and another was reputedly shed ascending to the scaffold on the last day of her life.

Shoes and ankles were an 18th-century obsession. Dresses were hitched up at the hem to reveal a glimpse of a gem-encrusted silken toe—the style was called venez-y-voir, or come and see. Marie Antoinette was no exception: a shoe junkie, on four new pairs a week. (In 1777, her brother-in-law Artois went further, ordering 365 pairs at once, a new pair for each day.)

These were the bedtime stories on which the infant Manolo Blahnik, whose name is now synonymous with fancy shoes, grew up. “My mother used to read me Stefan Zweig’s biography of Marie Antoinette, carefully skipping over the more harrowing details of the guillotine, of course,” the designer recalls. “From that moment on, she became a lasting source of fascination for me throughout my life. The way she dressed and presented herself was a kind of performance that has stayed with me. She is fashion’s first real icon.”

When he started creating shoes in the 1970s, Blahnik would study the footwear in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), finding inspiration for his own fantastical designs. Later, he made dozens of pairs for Kirsten Dunst when she starred in Sofia Coppola’s 2006 film about the queen’s life.

Now Blahnik is the sponsor and partner of Marie Antoinette Style, a new exhibition that runs at the V&A until 22 March 2026, and he has launched a capsule collection of 11 styles to coincide with the show—with the doomed queen serving as the muse behind each piece.

The Rohan, in rococo powder-puff pink and blue, memorialises her rouged complexion. The bejewelled Valois, in tawny pink silk, has a box-pleat detail and frayed silk fringing. They are spike-heeled and narrowly pointed, so authentic in spirit that even today one must suffer a little to wear his creations.

Only a few of Marie Antoinette’s own shoes survive—they were presumably cast-offs passed on to servants or friends and preserved ever since as precious relics. Narrow, pointed and soled in fine leather, with uppers of embroidered silk, damask and brocade, and vamps trimmed with buckles, ribbons and gemstones, they show that she favoured pointed mules.

A single poignant survivor in cream silk with a low leather heel, lost on the day the mob invaded the Palace of Versailles and now kept in the Musée Carnavalet, comes closest to being what we might call a “sensible” shoe.

Ruth Guilding