Van Gogh’s Starry Night over the Rhône (September 1888) gives a marvellous insight into the artist’s life and work in Arles, in Provence. Seeing both the painting, now at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, and the place where it was created offers a wonderful opportunity to work out what came from the actual view—and, importantly, what emerged from Van Gogh’s artistic imagination.

To begin with the obvious, the stars of the depicted Plough (or Big Dipper) would never look quite so prominent, even in the relatively muted artificial light of 19th-century Arles. In the actual sky, the Plough points to the North Star, so these stars would have appeared behind Van Gogh when he was looking south at the view towards the centre of Arles. He moved the Plough to the opposite part of the sky, in order to include the universe’s most recognisable set of stars in his painting.

Van Gogh framed his view from the small port at the northern end of Arles, on the edge of Place Lamartine. He must have stood on the embankment, just above a sandbar that was used for loading and unloading boats. His home, the Yellow House, lay just three minutes’ walk away on the other side of the public garden. The view of the Rhône is one that he would have seen virtually every day.

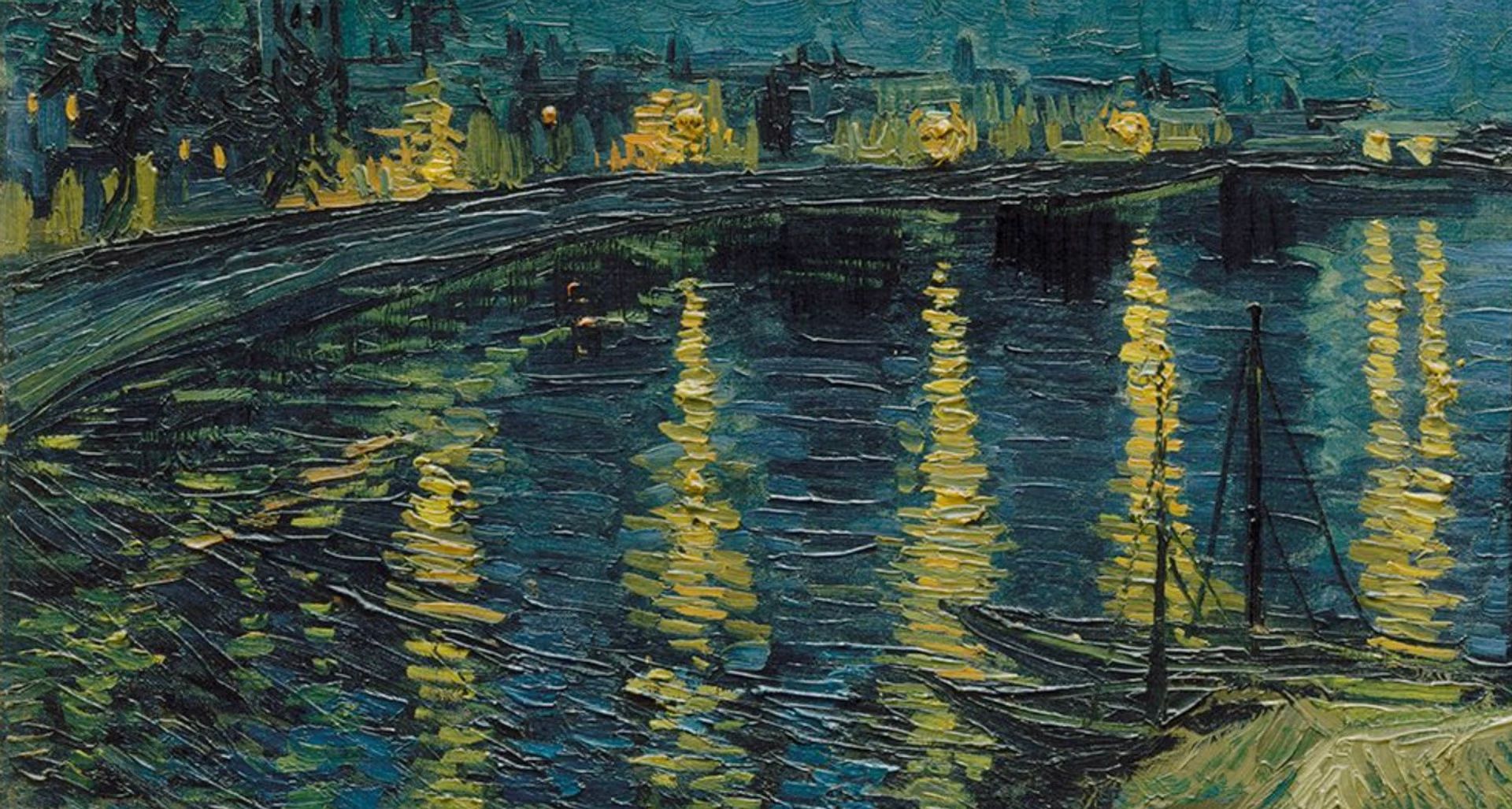

Van Gogh’s Starry Night over the Rhône (detail)

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

The street lamps along the Rhône embankment would have been far dimmer than those he depicted. They were gaslights, which then had a brightness of around 20 watts (a standard household bulb today is 60 watts). Van Gogh has positioned them roughly every 100m, so even the closest one in the painting would hardly have been noticeable. The most distant lamp in his picture would have been nearly a kilometre away, so completely invisible.

Light from the street lamps would have barely reflected in the river. Not only were the lights very weak, but the water of the Rhône hardly provides a mirror-like surface; it rushes past Arles on its way to the Mediterranean.

Vincent wrote to his brother Theo on 29 September 1888 that the picture was “actually painted at night, under a gas-lamp”. He may have outlined the scene by the riverside, although he probably did most of the painting back in the comfort of his studio. Decades later, the story emerged that while on the riverside he had worked wearing a hat with candles placed around the brim. This seems very unlikely as such headgear would have been most impractical, as well as highly dangerous.

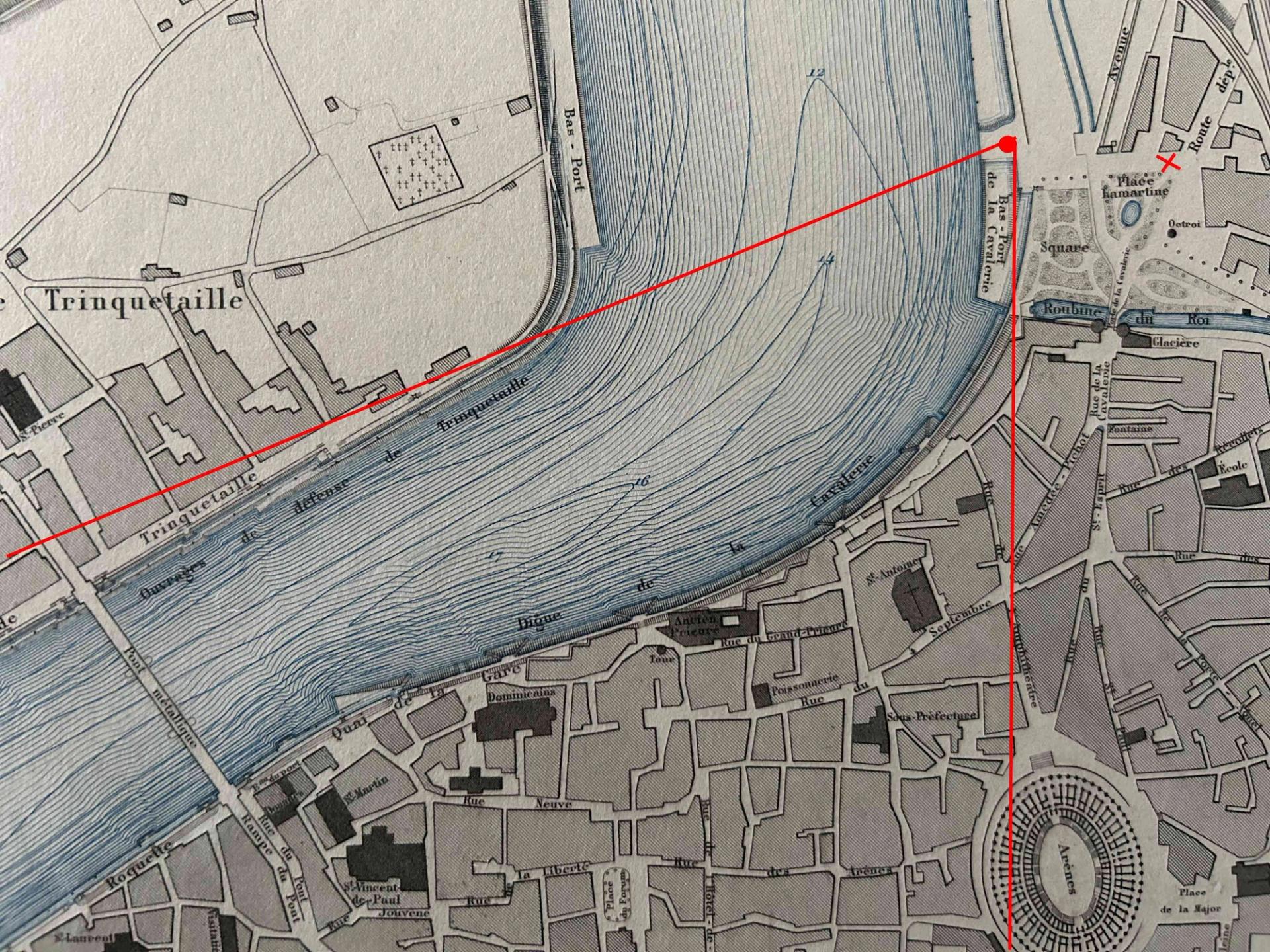

Map of Arles (1892), a detail showing Van Gogh’s view for Starry Night over the Rhône (marked out by red lines), the nearby Yellow House (indicated with a cross) and the public garden in front of his home

Martin Bailey collection

Van Gogh presented a reasonably accurate view of the horizon in the painting. The historic centre of Arles is on the left. Then comes the bridge over the Rhône (although barely visible in the painting, it is above the slightly darker area of water in the centre). Finally, the small strip of the suburb of Trinquetaille, on the other side of the river, can be seen at the right of the composition.

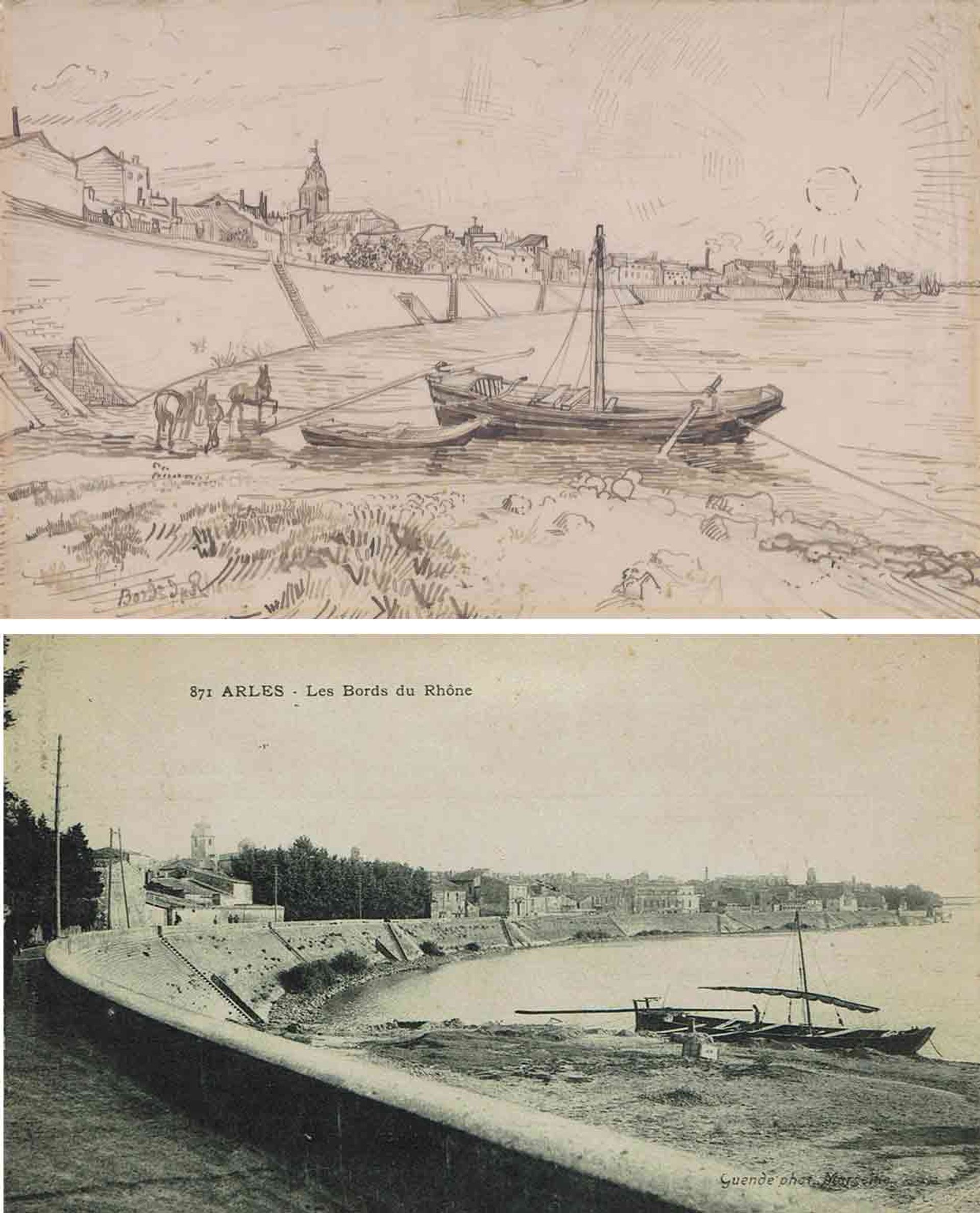

In the foreground Van Gogh depicted two sailboats moored by the sandbar, a feature which can also be seen in one of his own drawings and in an early postcard.

Van Gogh’s View of Arles on the River Rhône (May 1888) and postcard of Les Bords du Rhône (Banks of the Rhône) (around 1905)

Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam (drawing)

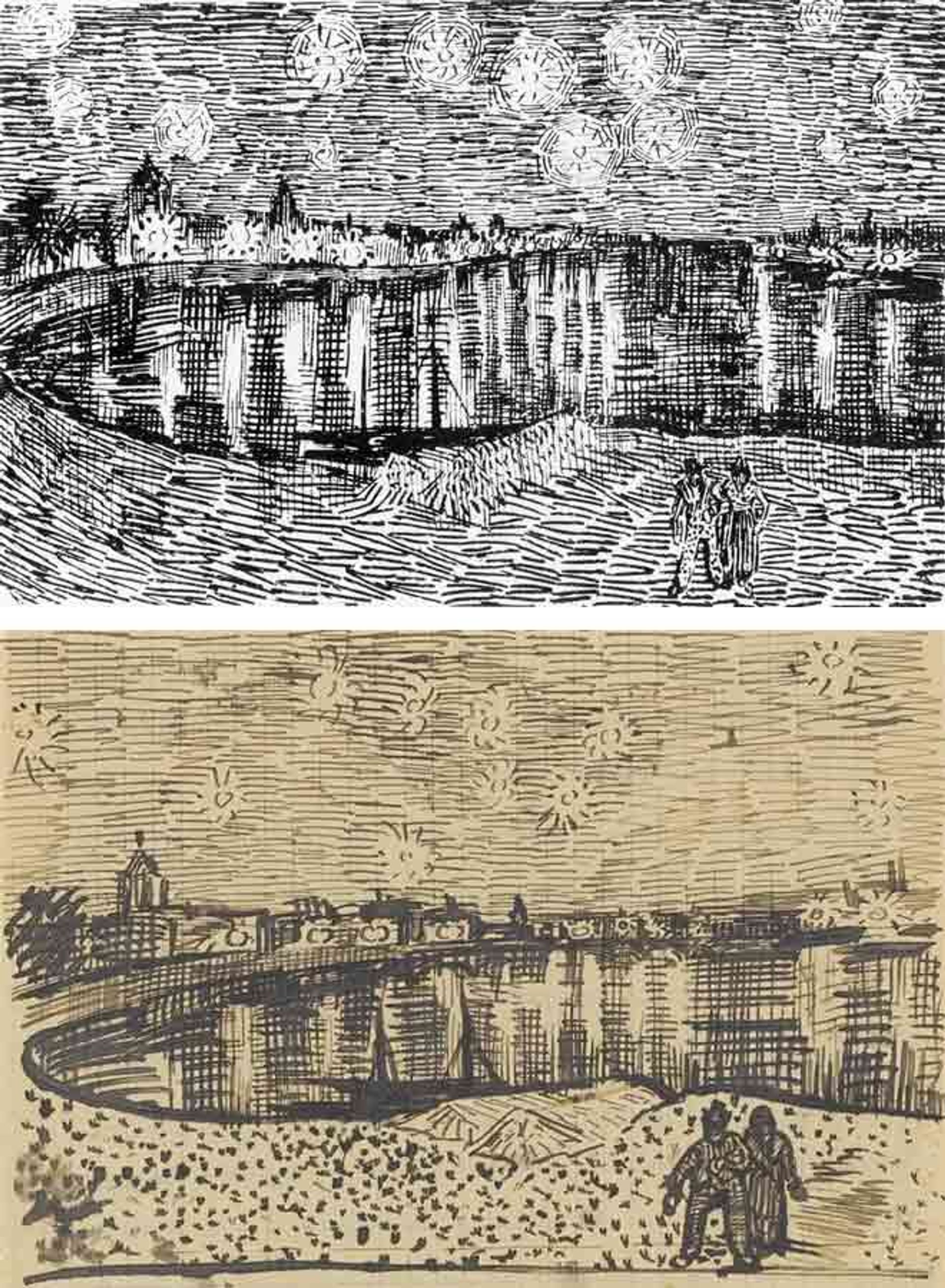

Some time after Van Gogh had filled his canvas he had second thoughts and fundamentally reworked the lower-left corner. But his original composition, now overpainted, can be seen in two small sketches which he made just a few days after the initial painting. These sketches depict a longer sandbank on the left.

Van Gogh’s sketches of Starry Night over the Rhône, sent to his brother Theo (c.29 September 1888) and friend Eugène Boch (2 October 1888)

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation) and whereabouts now unknown (reproduced in Emile Bernard, Lettres de Vincent van Gogh, 1911, plate lxxii)

In the painting, as finally reworked, Van Gogh turned the lower-left edge into water, making the sandbar much smaller. This larger expanse of water gives more emphasis to the reflections of the street lamps.

Van Gogh was pleased with the painting and chose it as one of two which he wanted to show at the exhibition of the Société des Artistes Indépendants in Paris in September 1889. It remains uncertain whether he altered his composition in autumn 1888, within a few weeks of doing the original picture, or in spring 1889, to improve it for the exhibition.

If one gets close to the picture (not easy when it is surrounded by crowds in the Paris museum), the later painted area of water in the lower left is clearly visible over the originally larger sandbank, as the directions of the brushwork are quite different.

The Indépendants catalogue named the picture as Nuit étoilée (Starry Night). This evocative title has stuck, reinforcing its attraction as one of the artist’s most beloved paintings (it should not be confused with his second Starry Night picture of June 1889, now at New York’s Museum of Modern Art).

When the Indépendants show opened in September 1889 the critic Félix Fénéon wrote about the Rhône scene: “Mr van Gogh is a diverting colourist even in eccentricities like his Starry Night: on the sky, criss-crossed in coarse basketwork with a flat brush, cones of white, pink and yellow, stars, have been applied straight from the tube; orange triangles are being swept away in the river, and near some moored boats strangely sinister beings hasten by.”

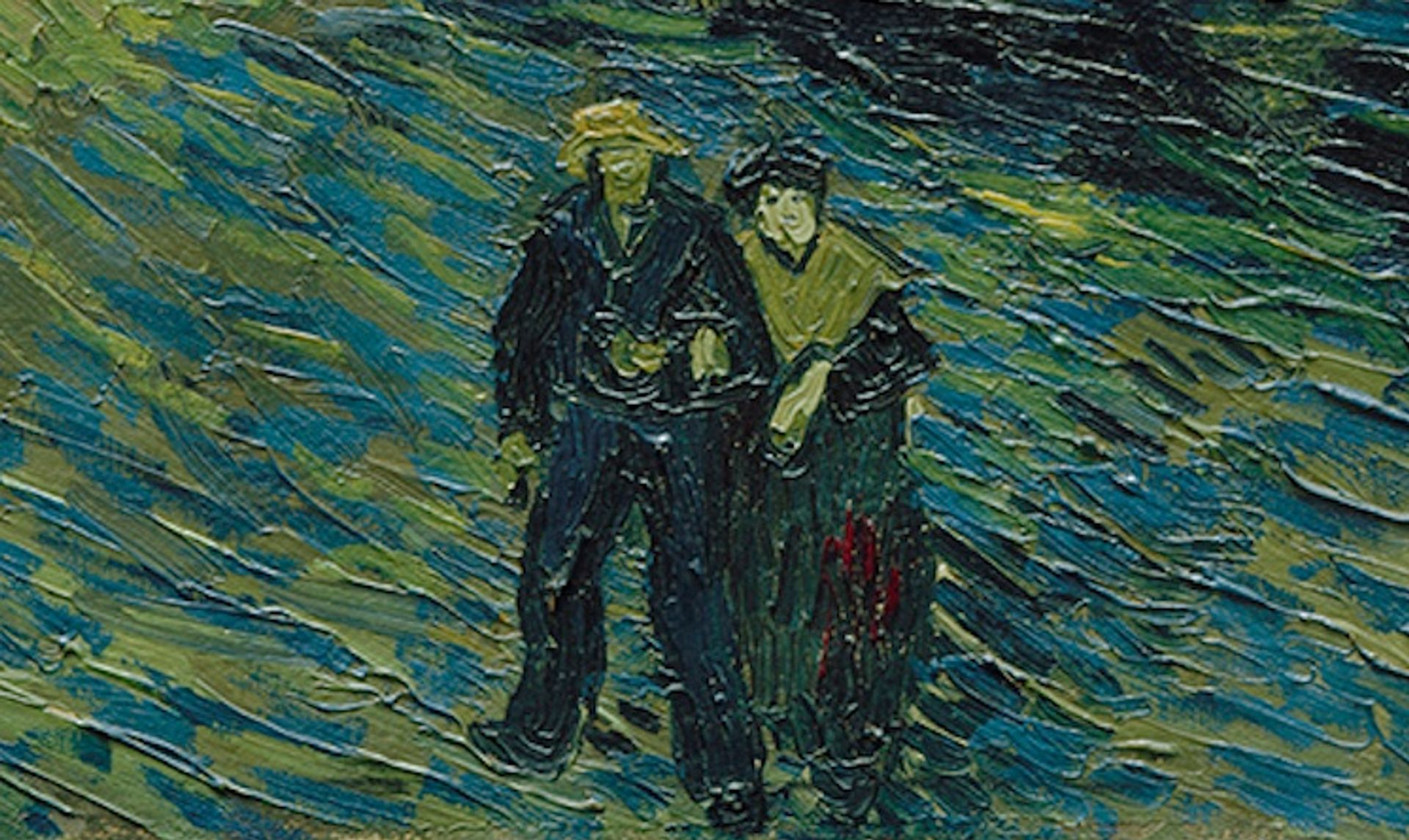

Van Gogh’s Starry Night over the Rhône (detail)

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Hastening “sinister beings” seems an unfortunate interpretation, since Van Gogh intended them as “figures of lovers” strolling arm-in-arm under the stars. The faceless man, garbed in blue and with a straw hat, bears a superficial resemblance to the artist himself. Some commentators have seen it as a self-portrait, although this is perhaps going too far.

For Van Gogh, the couple are there to add human interest and scale. Placed upright at the very bottom of the foreground the canvas, they seem to stand on the very edge of the frame. Starry Night over the Rhône represented a key work in the exhibition Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers, at London’s National Gallery (closed 19 January).

REVISED: Originally published on 7 June 2024, this blog post was updated with new information on 22 August 2025.