The exhibition Of my life at Kunsthalle Basel brings together the American artist and activist Ser Serpas’s multifaceted practice as a curator, painter, sculptor and performer. Serpas is best known for her assemblages created entirely from found and discarded materials, a contemporary reworking of Marcel Duchamp’s readymades attuned to the conditions of late-stage capitalism. While Serpas is scouring the kerbs of Basel for jettisoned objects, Of my life puts new emphasis on her work with a paintbrush. Embodying the art critic Harold Rosenberg’s dictum that the canvas is “an arena in which to act”, her paintings index activities as they unfolded in the studio and will do double duty as props and backdrops in her on-site collaboration with the Margo Korableva Performance Theatre.

Speaking from Basel, Serpas tells The Art Newspaper about the inspirations guiding her sourcing process, her history of artistic partnerships and the paradox of artistic value during a month largely defined by commercial art fairs in a Swiss city full of hallowed institutions.

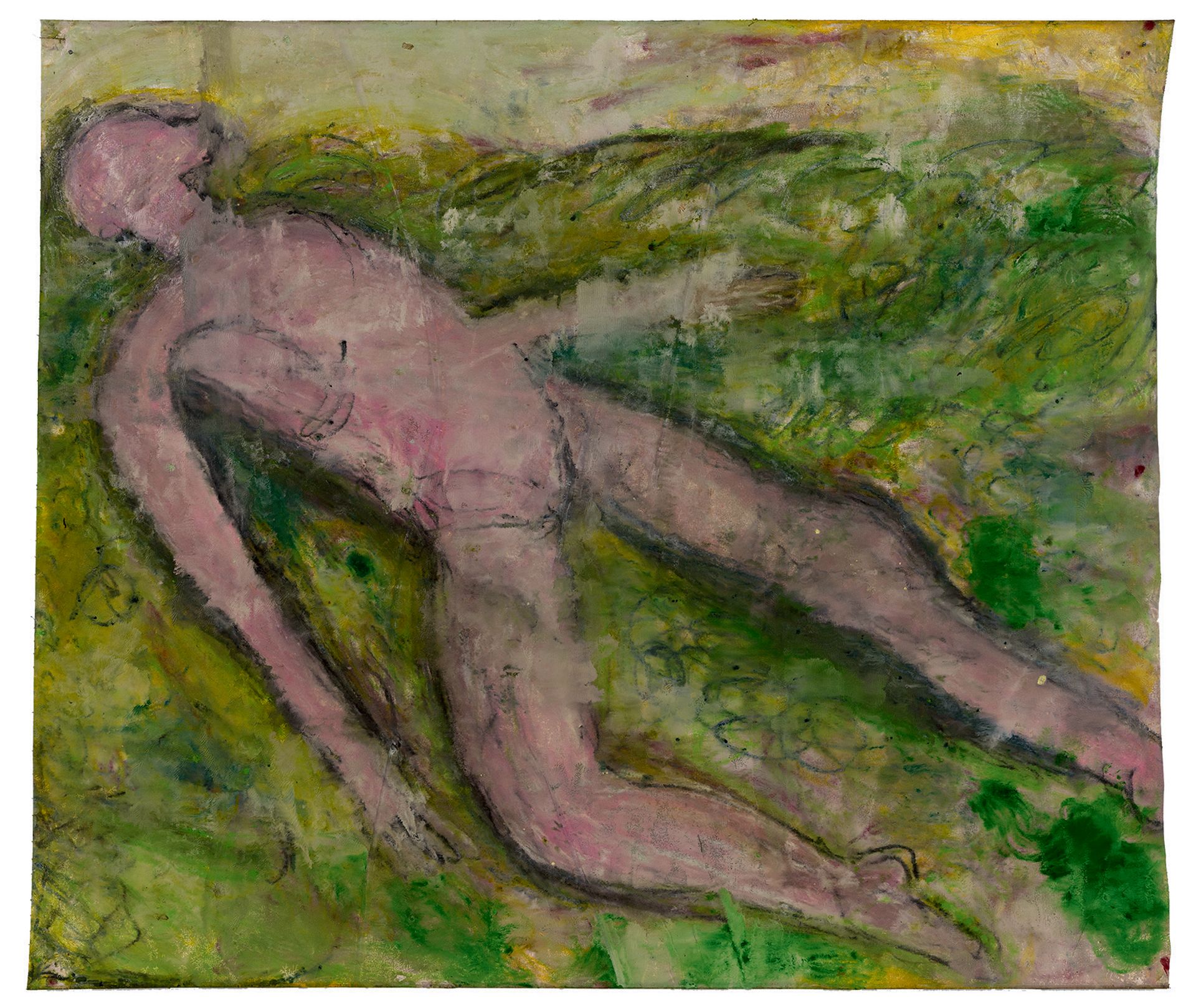

An untitled work from the artist’s new series of paintings, which she creates alongside her sculptures Courtesy of the artist and Maxwell Graham, New York

The Art Newspaper: Your Basel exhibition includes a collaboration with the Margo Korableva Performance Theatre from Tbilisi, Georgia. What is the background of this partnership?

Ser Serpas: I’m working with a director named David Chikhladze, who founded the Margo Theatre. David was one of the first artists who caught my attention when I was curating the Oxygen Biennial in Tbilisi in 2021. After that, I wanted to do a show where I could create a set for some of David’s original pieces and recontextualise them with my work.

David and I are very like-minded in our sensibilities. His videos from the 90s are my favourite type of video work: they look like music videos. I always say that my favourite artwork is the alternative trailer for Harmony Korine’s 1997 film Gummo. But David’s work still feels ultra-contemporary and, hopefully, the show will generate more interest in Georgian performance art, which responded to the collapse of the Soviet Union in a wild and multifaceted way.

You previously described looking for a “palette” when sourcing materials. How has that process played out in Basel?

In Basel I’m seeing a lot of pale whites, light browns and some blues, which is the palette I had in my first show in Zurich at Luma Westbau in 2018. The show in Basel will have four performances: the first in the museum lobby and the next three in the innermost galleries. I am showing paintings at a pretty large scale, but I’ve also built stages for the performances, including lighting design and sculptures that are quasi-props to be used by the performers. So they are going to operate a bit differently than my usual sculptures, but they’ll still have a similar attention to palette.

The paintings in this exhibition seem to be an extension of your sculptural practice. Could you describe the process and context of making them?

They’re all scaled up—most of them start at ten feet long. I had a similar process with a piece called Studio Party that was at the 2024 Whitney Biennial, essentially a record on a plastic tarp of things that were happening on the studio floor while I was making sculptures. There are also other backdrop works that record everything that happens on my studio walls, like the outlines of different paintings or paint scraped from the palette.

I’ve been doing this in a smaller format for a few years now, but I decided to up the scale and say, “OK, if I wear it down the right way, it can be a backdrop, a prop or a floor for something.”

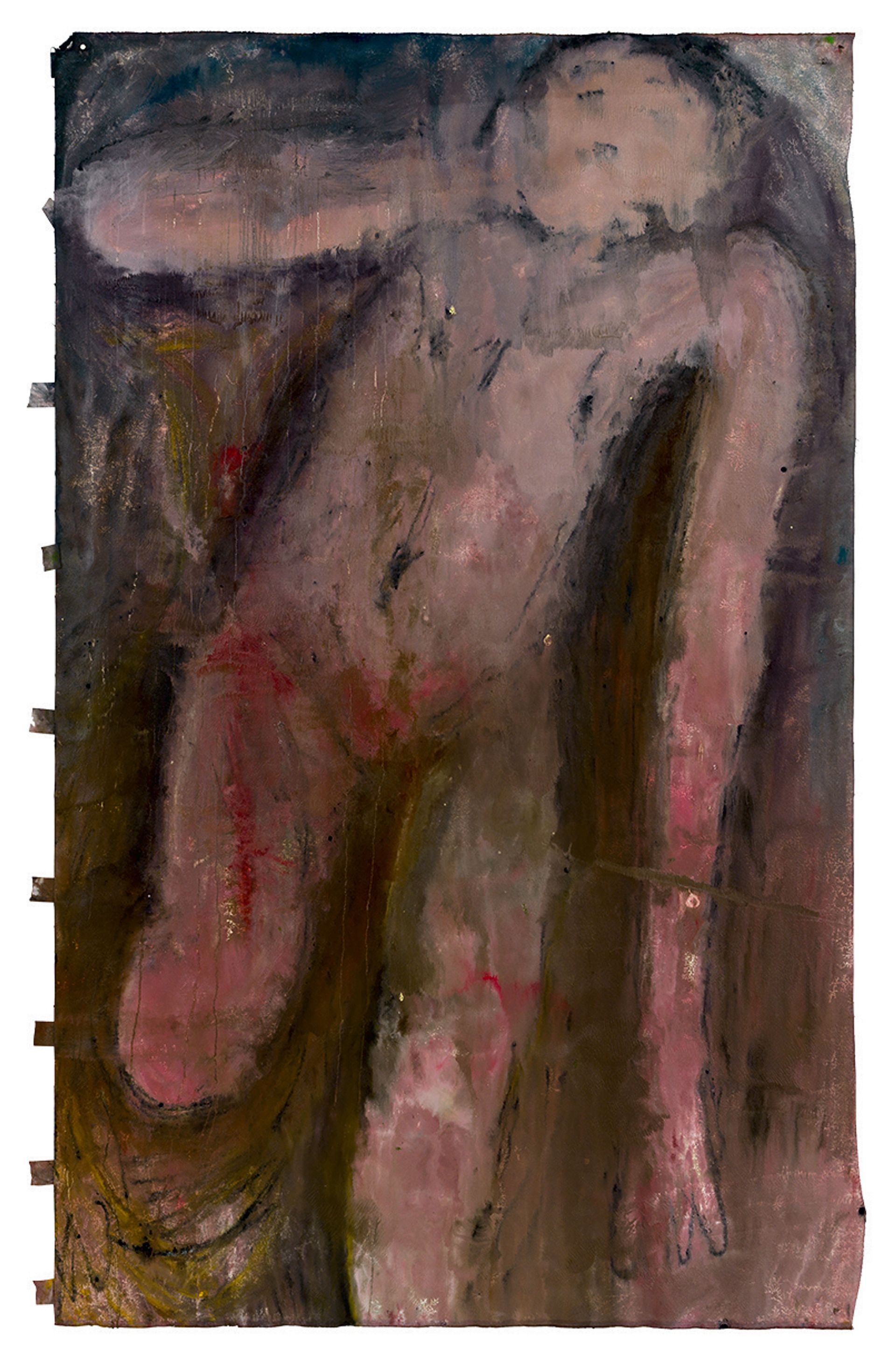

Untitled (2025), which will feature in Serpas’s show at the Kunsthalle, along with sculptures and performances Courtesy of the artist and Maxwell Graham, New York

One advantage of your approach is that you do not need to ship your finished works. As more artists explore local production or alternative transport, how do you see your practice aligning with broader climate-conscious efforts in the arts?

It was a response to my own limitations and economic circumstances, like not being able to afford a studio where I could work at scale. I set a list of rules for how I work, and it feels like the correct way to work at this moment in time.

It’s also a bit of tourism. In getting to know the install team at these places, I always get a pretty good read on wherever I’m like, “Oh yeah, I know this area. Let’s go eat here and I can tell you about the time that I found a crazy bed frame over there, and then almost got into a fight with somebody who was trying to claim it before me.” It’s something I want to continue to do as long as I can physically lift, like, a big fucked-up table over a fridge.

My sculptures are difficult to contend with for many collectors and institutions, and I do wish more people had them in their homesSer Serpas

Your work often examines construction of value by transforming discarded materials into temporary installations, then jettisoning them back into public circulation. How do you see that approach operating in the context of Basel’s art-fair season?

Different facets of my practice fall into different places with this issue. For the first time, I’m showing paintings in a pretty traditional way, and I know that’s going to ask a lot from people who are familiar with my sculptural practice. The sculptures are difficult to contend with for many collectors and institutions, and I do wish more people had them in their homes. Some people do, but not as many as the paintings, drawings or even some of the sound-based multimedia pieces I’ve made.

I used to live in Switzerland, and my friends work every part of the fair, so I know I’m going to have the best time. But I’m also hoping I can add a bit of what I think is a healthy dose of unease—“Oh, this isn’t really catered to me right now”—and having something that’s maybe going to smell bad and make the day more interesting for the hordes of art-world people here.

• Ser Serpas: Of my life, Kunsthalle Basel, until 21 September